Folded into a cone, dabbed with corncob jelly, sprinkled with nori shrapnel, the basement ham hors d’oeuvre Edward Lee sometimes passes at his Louisville restaurant MilkWood comes with a good backstory. Catch Lee in the kitchen and he’ll tell of the friend who found a brace of five-year-old Kentucky hams in another friend’s basement, knew their mold shrouds were signs of healthy maturation, and knew Lee would know what to do with them.

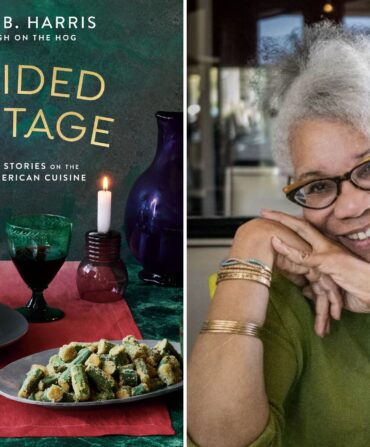

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

Chef Edward Lee

Bite into one of those lovely and meaty little packages and a roundhouse kick glances off your palate. First comes the pinprick of salt. Then the calm sooth of sweet corn. And the leathery crackle of seaweed. Followed by the prolonged umami reverb that comes when hams gain age and funk. And the recognition that you’re in the hands of a playful chef who lays down flavors like domino bones.

A Brooklyn, New York, native of Korean ancestry, Lee fell hard for Louisville during a 2002 Derby Week visit. By the time the next Thoroughbred earned a rose blanket, he had become the chef and co-owner of 610 Magnolia, a jewel box restaurant in an oak-sheltered neighborhood dense with Romanesque architecture. Soon, he was winning a tribe of followers while cooking dishes born of the French canon. Think frog leg confit with watercress pistou. Imagine foie gras torchon drizzled with plum confiture.

In this culinary-obsessed moment, running a great white-tablecloth restaurant is not enough. To keep up with the Kellers, top-tier chefs also have to publish doorstop books and open downscale analogues to their upscale mainstays. Lee checked those boxes in 2013. He published Smoke & Pickles, a meditation on graffiti art and cultural identity disguised as a cookbook, and he opened MilkWood, a cellar rumpus room of whitewashed brick walls, lipstick-red banquettes, and a ceiling crossed with timbers that recall charred bourbon-barrel staves.

Tucked beneath Actors Theatre, a downtown treasure with a rep for shepherding avant-garde productions onto the national stage, MilkWood broadcasts a different side of Lee’s personality. The side that knocks back three-finger shots of whiskey like they’re branch. And belts out karaoke without irony. The side that smokes braised octopus tentacles and calls the resulting invention bacon. And rethinks a fried chicken platter as a mosaic of cleavered parts and torn waffles, painted with Korean chile paste. For a burgeoning Louisville restaurant scene now reaching for new heights, MilkWood sets the bar.

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

Fresh Approach

Sorghum and grits ice cream.

Second restaurants are slippery integers in that chef-as-star calculus. Try to replicate your flagship, as too many folks did a decade back with Vegas money, and you devolve into a paint-by-numbers artist. Better to go down-market and complement your Saturday night restaurant with a Tuesday night joint. That formula worked for Donald Link, the New Orleans chef who honed his reputation at Cochon and burnished it with Cochon Butcher, a meat market and sandwich counter. Ditto Andy Ticer and Michael Hudman of Memphis, who opened Hog & Hominy as a casual pizzas-and-sandwiches answer to Andrew Michael Italian Kitchen, their white-tablecloth original.

The promise of second restaurants is great. They stand to deliver intimacy. Between a chef and his public. Between a diner and his companions. They offer a glimpse of what chefs really want to cook. In the hands of Lee and Kevin Ashworth, MilkWood’s young executive chef, that promise translates as a kind of house party cuisine, the cooking you might crave if you showed up in their kitchen at two in the morning, hungry after a night on the town.

Get the beef brisket, swaddled in sawmill gravy and crumbled biscuits, and it arrives topped with strips of grilled mortadella. Order the pork burger on a pretzel bun, crowned with kimchi, and lean back from the table to argue over whether the garnishing curl of pork rind looks like a mustache or an inchworm. Bite into the braised oxtail dish and try to discern the textural differences between pearls of spaetzle and orbs of fried hominy. Cut into the teres major steak, drag it through the chimichurri, and mark the pleasant intrusion of lemongrass. Choose ice cream for dessert and soon you’re dipping into a delirious bombe that’s raspy with grits and sweet with sorghum, framed by torn pieces of croissant and drizzled with coffee syrup.

Cooked by lesser folk, this food, which references Asian climes and rummages Southern larders, might be called fusion. But Lee and Ashworth don’t do shotgun marriage cuisine. What they do, instead, is prove that the best second efforts are passkeys to understanding creative culinary enterprise and harbingers of the future of chef-driven Southern cookery.