They arrive on wings of ocher, smoke smudges against the gray sky. It’s that time of morning a bit before morning, when the sun below the horizon is but a sooty promise. I hear the ducks squealing, tremulous like the Screaming Mimis of a Fourth of July celebration. They are incoming—that much I can tell. But in a world of muted light and dark timber, I struggle to fix their location. The first three streak over at treetop level, in range, but too quickly. Two more alight behind me, before I can twist around and get a shot. Another handful are settling down twenty yards in front, wings cupped and committed, and I raise the shotgun, but too late: They vanish against the dark curtain of the tree line. Now my heart is pounding. In a beaver swamp, on a wood duck morning, you never know if the last bird you’ve seen will be the last bird you’ll see or if this is merely the vanguard of a feathered storm.

I resettle. Shift the shotgun muzzle toward the gap in the trees carved by the creek and hike the shotgun butt into the pocket below my shoulder. Pull yourself together, I mutter. I’m breathing hard, as if this is the first time I’ve ever done this. Except I’ve been here a thousand times.

“Just wood ducks.” How many times have I heard that? An uncountable figure. In my neck of the swamp, straddling the Piedmont and Coastal Plain of North Carolina, wood ducks are the duck hunters’ coin of the realm, by far the most common waterfowl taken—and on many hunts, the only waterfowl taken. Early in the season, a good wood duck hunt seems a gift. But too many are too quickly jaded by these jewels of the Southern swamps. Familiarity breeds a smidge of contempt. “How’s it going?” I ask my hunting friends a few weeks into the season. “Pretty good,” they’ll say. “Mostly just wood ducks, though.”

It’s only when the sun breaks free of the trees, and you wade over to pick up a downed bird lying still in a corona of sparkling green duckweed, that you feel the full measure of the moment. Aix sponsa, the “water bird in a bridal dress,” is a riot of color. Pompadour of iridescent green. A spotted russet chest, like snowflakes on a log. Lemon flanks and blue wing patches as rich as lapis. And a startling bloodred eye, eye-ring, and even eyelid. No matter how many mornings I hunt, the reaction is always the same: In all of animalia, is there a more beautiful bird than a wintertime wood duck drake?

Just as impressive as their runway looks are their drag-strip performance metrics. Wood ducks are built for a specific combination of speed and agility: wings shorter and broader by percentage than nearly any other duck’s, a rudder-like tail longer and more squarish than nearly any other duck’s. The bird is a feathered Corvette, with a blistering zero-to-see-ya-later blastoff speed and the ability to juke and jive through interwoven tree branches so dense you wouldn’t think an ill wind could pass through them.

I had scouted the swamp the previous morning, because the best way, and often the only way, to kill a wood duck is to know where it wants to be and be precisely there. Not close to there—exactly there. Decoys work, but just a little. Calling works, but even less. To tip the odds at least in your general direction requires watching the birds in real time a day or two before the hunt. Find the spot, and be ready.

The farmer who works this land, rolling and creek riven and heavily timbered, is a dear friend who knows me well. When his family was working out hunting leases to their several thousand acres of farmland and big woods, he asked his father to hold out this little piece of beaver pond and flooded stream for me. “I told Daddy,” he explained to me as we chatted late one morning, pickup truck window to pickup truck window. “I said, ‘Daddy, you know that Eddie Nickens loves a swamp like Peter loved the Lord.’ So we want you to have it for duck hunting.” I’m not sure I’ve ever received a higher compliment.

Now the light is up, and I have two ducks in hand and one more to go, and the full beauty of a wood duck swamp comes to light. Jacob’s Ladders of sunlight stripe the air, and the topmost tips of the cypresses are afire. The sky is finally blue, and the first crows caw, a portent, I’ve learned, that the wood duck flight is nearly over.

But there is often a straggler or three, birds that hit the snooze button. And this one comes flying down the creek channel, head erect and searching for company. If decoys work at all, this is when they are at their best, and my half dozen hand-carved wooden birds do the trick. This hot rod of a duck deploys the drag parachute, wings set, webbed feet askew, finding passage through the labyrinth of branches as the gun comes up and the muzzle blots out the bird, and I pull the trigger without thinking about pulling the trigger.

Three ducks. A full limit. An out-of-the-way piece of flooded woods. A sunrise for the ages, just like every sunrise in a wood duck swamp.

I once had a friend who disparaged these ducks. I’d asked him how his season was going: “Wood ducks, wood ducks, and nothing but wood ducks,” he spat, with seeming disgust. “I am sick and tired of wood ducks.”

As I said: I once had a friend.

See the other articles in our For the Love of the Game collection:

In Pursuit of the Ancient Tarpon of the Everglades, by Monte Burke

Man vs. Turkey: The Quest to Outsmart a Gobbler, by David Joy

Chasing Chinook—and Family Memories—in the Waters of Alaska, by Kim Cross

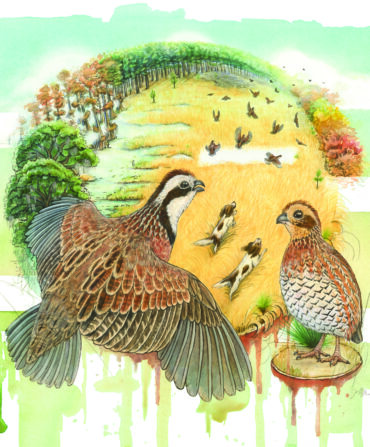

A Quail Hunter’s Ode to the South’s Signature Game Bird, by Russell Worth Parker

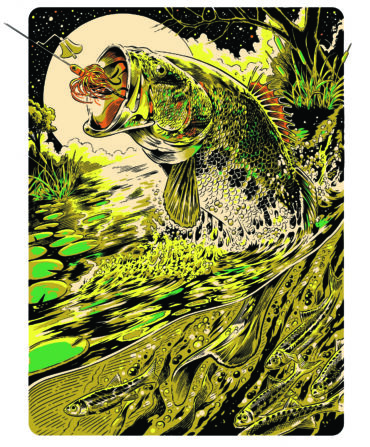

A Love Letter to Largemouth Bass, by Charles Gaines