All beginnings set us up for endings. As a farmer, I know that well. A farm is a living, breathing thing, and the changes I see almost daily remind me that time is fleeting, and nature is cyclical. We plant seeds and harvest crops. The sunny days of today will give way to clouds and rain, but the sun will come back, and the cycle will repeat itself.

Our South Georgia farm sits off a loose sand road in rough but beautiful country—just thirty miles due east of the Okefenokee Swamp and home to gators, snakes, and a king’s ransom of insects. My wife and I have three kids, two boys and a girl. We farm pigs that we raise on pasture, meat chickens, and eggs, with a smattering of vegetables and citrus. It’s a fairly bucolic life. A good life. The kind I lie in bed at night and feel thankful for.

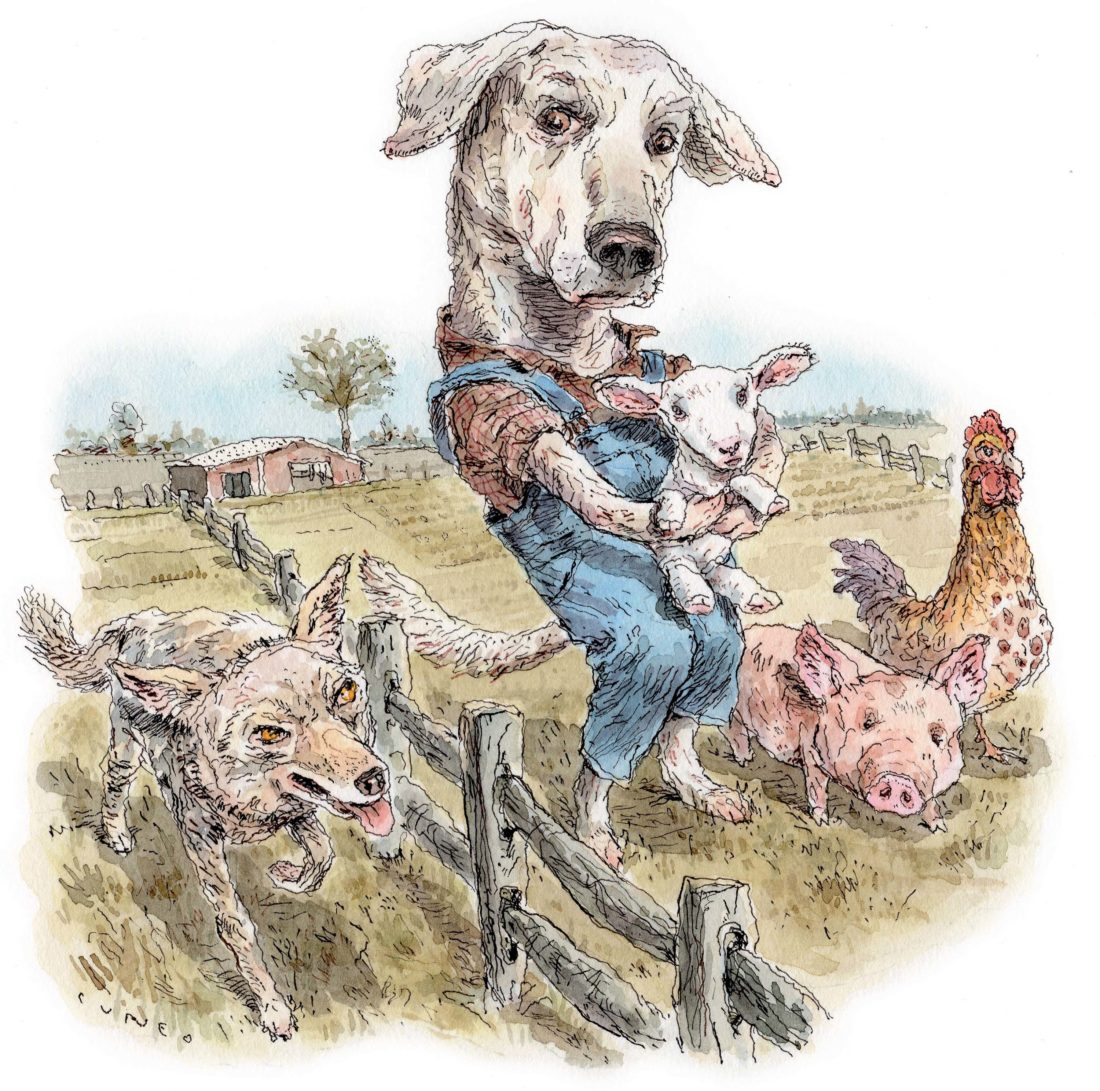

There is a special glue that holds us all together, more than the dirt and the chores. Our dogs. The luckiest dogs on earth. Loved beyond measure. They help me work. They give my daughter “pony” rides. They help my boys hunt squirrel and rabbit. The farm just wouldn’t be the same without them.

The property was once part of a plantation, but by the time we came along in 2014, it had changed hands many times and surrendered to a tangled mess of pine, oak, grapevine, and briar that took months to clear out. It is in what locals refer to as “the north end” of Camden County. Last county on the Georgia coast before you get to Florida. The terrain is as flat as a lake on a windless day, interrupted only by deep drainage ditches along the dirt roads, which wash out after heavy rains. In our pastures, our pigs routinely root up one-hundred-year-old clay turpentine cups, properly called Herty cups. They appear peeking out of the black sand, relics from the days when the longleaf pine ecosystem ruled this area. I imagine men in overalls and brogans wandering these remote woods, leading a mule and wagon and collecting the sticky pine resin from tree after tree, day after day. At night I swear I feel their ghosts breathing down my neck. It’s the kind of place that either draws you in or pushes you away, no middle ground. I love it. So do the dogs.

I spend a lot of time working alone, with only the dogs for company, and over time we’ve learned to understand one another as members of the same pack. We’ve come to an unspoken agreement. I’ll protect you and you’ll protect me, and as long as we’re able to live, we’ll do it to the utmost. You’ll live in a dog paradise, with the run of your thirty acres. You won’t know the tether of a leash. In the winter you’ll be free to sleep where you find warmth, and in the summer you can cool down in the creek. The rest of the world will remain outside our gates. This is our kingdom.

I share that bond with two livestock guard dogs, Mags and Paws, both majestic Great Pyrenees; Chase, a part-Pyrenees mutt with a taste for wild rabbit; and Otis, a black pit-Lab mix I found in the woods on a cold winter day, starved and chewing on a pine cone. Then there was Chance—Old Chancey Boy, the old Sarge. The toughest old dog I’ve ever seen. He joined the pack some years ago, just after we’d lost two dogs on the same night to unrelated causes. The first died of old age on the porch, and the other at the vet’s office after getting into coyote bait some jackass had put out down the road. Around that time, someone showed up at the vet with two dogs, identical brothers. They were abandoned, hungry, and well past their prime. Both were heartworm positive. One died at the vet’s office. The other was Chance.

The vet called to ask if I’d take him. For some reason, if you own a farm, people think you’ll take an endless parade of canines. Of course, I obliged.

No one knew his exact age, but I’d guess he was eight or nine, maybe older. He looked like a full-blooded yellow Lab. His eyes had begun to gray around the edges, and age had taken the bounce from his step, but he got along pretty well, like an old dependable pickup truck that won’t win a drag race but won’t leave you stranded on the side of the road, either.

From the moment he arrived, Chance was in his element. I cured his heartworm with sheep wormer and got him back in match shape. Like a farmer’s foot slipping with ease into a well-worn work boot, he seamlessly found his place in the pack. On a farm, you have different kinds of dogs, all fine animals in their own ways: guard dogs, working dogs, and lying-around dogs. Chance was mostly the lying-around type. He loved sleep, food, and wallowing in the dirt trying to scratch that impossible-to-reach spot on his back. Lurking just underneath his seemingly carefree demeanor, though, was a palpable wisdom.

Chance took to ambling behind me as I fed the animals. Content in his own skin and seeking no approval from me, he wasn’t the crowding type and didn’t have a neurotic bone in his grizzled body. But he was always in my vicinity, poking and sniffing around the dirt. He was good to alert me to snakes in the tall grass and seemed to enjoy protecting those around him. With the chickens he was gentle. Around the more rambunctious hogs he was stern. I rarely saw him growl, but I never saw another animal cross him. Chance reminded me of a soft-spoken grandfather who had weathered life’s storms long enough to see old age, the kind of man who doesn’t have to yell and scream to get his point across. His very being seemed to be enough to give pause to anything looking to exploit any perceived old-dog weakness.

As he got older, I worried he wouldn’t make it through the winter. When spring came along, I worried he wouldn’t survive the heat of summer. This dance went on for years. Me doubting him and him paying my uncertainty absolutely no attention. He was ageless, infinite, giving the middle finger to time. In all the years I knew him, he never changed much. When I’d bring him up to friends, they’d say, “Shit, that dog is still alive?” Bet your ass still alive. Still following me around as I work. Still eating his weight in table scraps.

Farm dogs aren’t like their suburban cousins. They don’t want to come inside. They’re more primal, wilder. I’ve seen a farm dog kill a coyote and care for a newborn lamb with equal tenacity. Many don’t like to ride in cars.

Once I took Chance on a drive up to the feed mill in my truck. Hell, I thought, he’s an old dog, and old dogs love to ride around. Not Chance. To say he was uncomfortable isn’t doing it justice. He was anxious and whiny, his tough exterior melting in the unfamiliarity of the truck. After he got back to the farm that day, he never rode in a vehicle again. He’d seen enough to know he didn’t need to see any more. With his own land to roam and a large barn to sleep in and all the animals to look after, he had all he wanted.

As a livestock farmer, I am reminded of death fairly regularly. Often my customers will ask me if I get sad taking a load of hogs to the abattoir or processing chickens. The truth is, no, I don’t. I am grateful and appreciative, but not sad. Daily I’m surrounded by magnitudes of life. I see babies born and flowers bloom, and at night the frogs can be so loud they keep me up. I also see death, and not only is it a part of life, it provides life. To be a livestock animal on my farm means you get a lot of great days and one bad one. We should all be so lucky. But when you work with dogs, you get into a rhythm, even with the lying-around types. It’s a beautiful thing. And when you lose a dog, that rhythm changes in a way that is profoundly heartbreaking.

On the day Chance died, he didn’t look any older than the day I got him, though he must have been fourteen or fifteen. Part of our pack’s agreement, I’d like to think, is that when it’s time to go, we go quickly. We don’t question it or run from it. When the quality of this great life slips into the ether, we follow.

I’ll always remember his last day on earth, one of those sunny late-winter days when the air teases you with spring. The pines thick with pollen. Frogs croaking in the swamp. The smells and sounds of the place that had come to inhabit his soul surrounded him. I laid him on the tailgate of the truck and cried, and my fist dented the steering wheel a few times. Oh how the death of a dog makes me angry. I carried him to that old, crooked pine where we lay our fallen dogs to rest. Even though I only knew him as an old dog, I picture him now as a puppy, running in a field, the wind at his back and his tongue hanging out, reunited with his brother and free from the heavy weight of age. Someday the rest of the pack will be running with him. Someday it’ll be my turn. And when it is, I couldn’t ask for a better sentinel to greet me as he wakes up from a nap and looks at me with those steady eyes, surely asking, “Did you bring any table scraps?” To Chance. Toughest old dog around. Long may he run.