The perfect Tampa Cuban sandwich starts in the palmetto fields in rural Central Florida. Just about every day, “the palmetto guy” (as he is known by many) heads to where the Serenoa repens is plentiful at a property he owns in Crystal River north of Tampa, as well as other choice palmetto spots. Danny (he prefers not to give his last name) dons Kevlar sleeves, gloves, and boots to go with a long-sleeved shirt and jeans. He walks into the hardy palmetto acres with a linoleum knife and starts cutting off fronds. With help from his assistant, they collect and load into the bed of Danny’s truck fifteen or so bunches each trip, each containing 250-plus fronds stacked on a longer palm branch.

Though Danny, who is 60, loves being outdoors, the work can be miserable. In the hottest months, the sun and humidity are merciless. The palmettos prick and slice. Rattlesnake sightings are common; Danny’s former assistant once let a pygmy rattler get loose in his truck. After rain flooded the palmetto fields not long ago, Danny came across a four-foot alligator. “He gave me a warning,” he says. “He made a noise, and I said, ‘Okay, buddy.’”

But his arch-nemeses are the common yellowjackets that make their nests in the ground near palmettos. “You don’t see them until they are on you, and then all you’re trying to do is get away,” he says. “They attack in bunches. Once one hits you, it stays on you and releases pheromones so the others can find you. They’re just mean. Mean, mean, mean, mean.”

Danny has been committing to this work full-time for thirty-five years. No one else has his job title, he thinks, in the entire world. And right about now, you might be wondering what this has to do with Cuban sandwiches. Answer: It’s about tradition. Dedication to process. Adherence to the details. And as anyone who makes a good sandwich knows, details are everything.

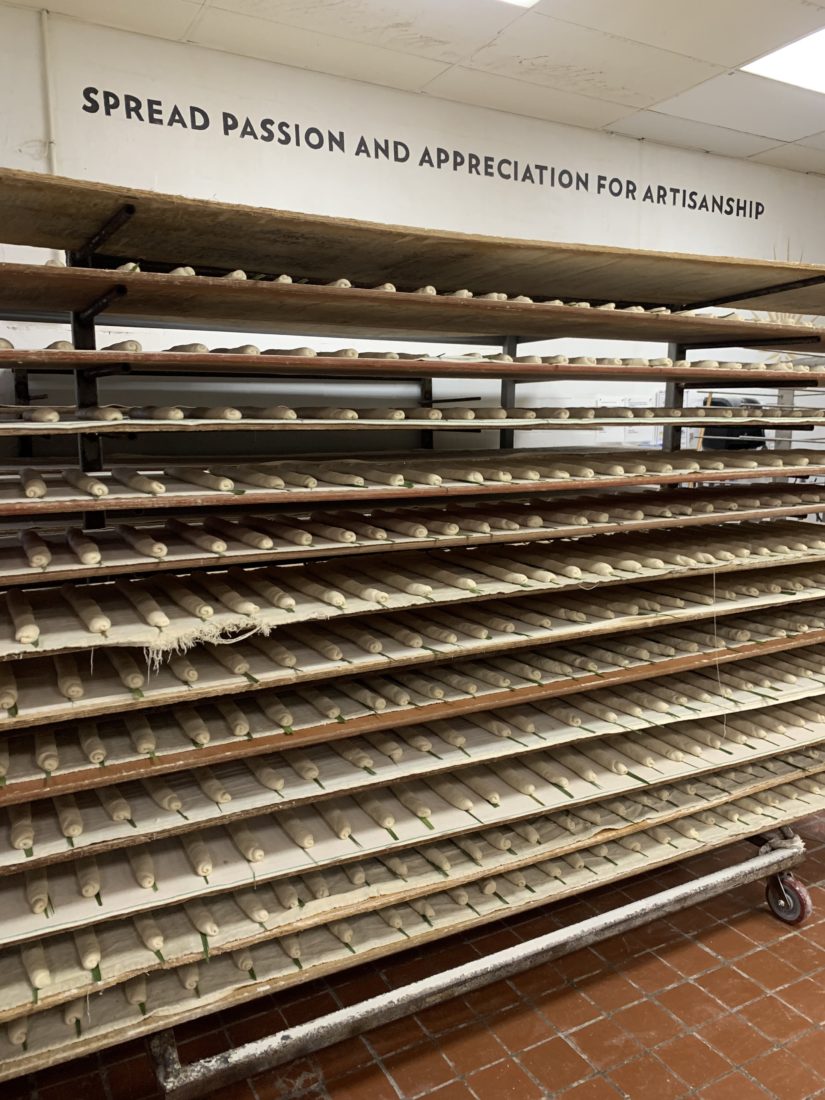

Danny delivers the palmetto bunches to places such as La Segunda Central Bakery in the historic Tampa enclave of Ybor City. A family-run business, La Segunda has been around since 1915. Along with a front-of-house shop that sells cookies, pastries, and Cuban food, the bakery leavens upwards of 18,000 loaves of Cuban bread a day. It’s a 24-hour, three-shift enterprise, shipping as far away as Alaska, and just one of several Cuban bread bakeries in town, including Faedo Family Bakery and Casino Bakery. They all need palmetto fronds from Danny.

Once Danny delivers the fronds, the bakers water them down, peel off the skinny leaflets one by one, and lay them individually on each long, doughy strip that will bake into Cuban loaves. The palmetto holds in moisture, they say, and it scores the dough so that when it heats and browns, the bread blooms along the length of the leaflet. The bakers could use twine or thin rope, but the palmetto leaflet on Cuban bread is a tradition dating back, some say, to bakeries in Cuba in the 1800s. It’s also one important difference between a Cubano you will get in Tampa and a Cuban sandwich you will get most anywhere else. “Everybody in Tampa has grown up with this,” Danny says. “It’s tradition, and they’re all about tradition.”

I grew up in Tampa. I was eating Cuban sandwiches in school cafeterias long before I knew about hoagies, subs, Reubens, or paninis. I still remember the day in fifth grade when John, a new classmate hailing from New York, called our school Cuban sandwiches “heroes.” He never really recovered from that gaffe. Which is to say, I once thought everyone knew what a Cuban was and how to make one. And I was very wrong.

Since those innocent days, I have lived most of my adult life away from Tampa. In that time, I have realized the sad truth that the Cuban sandwich is often loosely translated, tastelessly gentrified. Zabar’s in New York City, for example, calls one of its paninis a “Cuban,” but it’s nothing more than ham and cheese on pressed ciabatta. (Ciabatta!)

If you are like me, you want to introduce people to the joys of a good Cuban. But the problem is, if you grew up in Tampa, it’s hard to find the kind you love.

I spent a good portion of this last year back in Tampa, visiting with family, getting to know the city again, and obsessing about my hometown’s sandwich (i.e., I ate so many Cubans that I lost count). I also got in touch with Andy Huse, a Tampa-based food historian and co-author of the forthcoming book The Cuban Sandwich: A History in Layers (University Press of Florida). Although Tampa and Miami frequently bicker over which is the “home of the Cuban sandwich,” Huse maintains there was never a Frankenstein moment when someone piled a combination of meats and other ingredients between slices of bread, pressed it in an old plancha, christened it a “Cuban,” and sent it staggering out into the world. Rather, like humans, the sandwich has evolved over time and location.

“It’s like a family, okay?” Huse says. “The head of your family tree is in Havana. And then there are branches, children. They grow up in different times, and they’re all immigrants, so they end up in different places. Coming to Tampa, the Cuban would have taken on some of the characteristics unique to the city.”

The Tampa Cuban came out of Ybor City, the “cigar-making capital of the world,” in the late 1800s. With Ybor City’s red-brick streets, factories, and cafés populated by Cuban, Spanish, Eastern-European Jewish, and Italian immigrants, the sandwich veered from its Havana roots to satisfy the city’s own working population.

Today, the Tampa Cuban is a combination of three complementary meats—ham, pork, and salami, each representing the early ethnic diversity of Ybor—along with a few other key ingredients. (Traditional Miami Cubans forgo the salami.) But before we get to the sandwich’s inner workings, it cannot be stressed enough that it all starts with that Tampa Cuban bread. The ingredients—water, salt, sugar, shortening, yeast, flour, and oil, massaged and stretched thin to about three feet per loaf—are altered slightly by each bakery. With the sacrament of the palmetto, the master bakers then judge the day’s outdoor humidity and temperature, as well as the general personality of the dough. When the time is right, they lay out the loaves on carts in front of the hot ovens, open the hearths, and turn on the bakery fan. The foreplay runs hot air over the raw dough’s exterior.

“This process instantly makes a really crispy crust on the outside, fluffy on the inside,” Huse says. “Not a lot of places take the time to do that.”

Only then are the loaves hand-placed in the ovens, where they bake for about 45 minutes give or take, based on the dough’s temperament. (Bread bakeries in Miami and elsewhere, it should be said, are not known for their commitment to the Palmetto Frond Rule or Hearth-Flirting Rule, though some might do it, and also Miami bread in particular is hand-made to be wider than Tampa’s, and in some cases kind of ovally.)

Bakeries wrap the loaves individually in plastic or paper while still warm and deliver them across the city and beyond. When you order a Cuban at a Tampa restaurant, the sandwich makers remove the dried and crumbling palmetto frond and slice the loaf to a length ranging between six and twelve inches, depending on the restaurant. Then, if they know what they’re doing, they layer (in the following order!) about four ounces of thinly sliced ham; one to one-and-a-half ounces of spiced, slow-roasted pork; and an ounce or so of Genoa salami. That’s followed by a semi-thin slice of Swiss cheese and two to three deli pickle chips piled on top.

They slather the inner portion of the top bread slice with yellow mustard or a mustard-mayo combo; some restaurants get frisky and add a “special sauce,” which is often mojo, but this is getting into gentrification territory. (Many Tampa shops ask if you want your Cubano “all the way,” which means adding lettuce and tomato, an addition that earns scoffs from the purists.) The sandwich is then closed, and the top and bottom slices of the bread brushed with butter. It is hot-pressed until the outer crust browns and turns crispy. The meats warm. The cheese melts. Before serving, the sandwich is sliced diagonally—the angle varies with each restaurant—and your eating journey usually starts at one sandwich half’s top corner.

Which brings us to the taste—the triarchy of those three meats with accoutrements presented in sufficient portions. When you bite into a proper Tampa Cuban, the outer bread crackles and crumbles before giving way to the sweetness of the ham, the salt-citrus of the pork, and the smoky spice of salami. The flavors, built around the fat of the meat, blend together in a culinary version of consonant harmony, especially when you get a bit of the funky-gooey Swiss and the gland-expanding mustard-mayo and pickles all shouting their own notes. A Tampa Cuban, in these moments, pops with an all-new singular taste.

“One thing I’ve always liked about the Cuban, and it’s certainly true of the Tampa one, is how all of the elements can come together and sort of make one master flavor, if that makes sense,” Huse says. “The parts become the whole. They really belong together, and it’s hard to extricate them.”

This past year, I thought a lot about the Tampa Cuban and its connection to the city and its people. I did this while eating a La Segunda Cuban and standing in a gravel parking lot located across the street from a white clapboard church with a yellow cross painted on the door. I thought about it while sitting at an outdoor picnic table along busy Hillsborough Avenue, inhaling a twelve-inch Aguila’s Cuban with lettuce and tomato (I sinned!) and slurping a batido (a Latin American milkshake/smoothie), and while eating a Cuban over a white tablecloth with my sister in the haughty-romantic decor of the Columbia Restaurant.

I thought about it in West Tampa Sandwich Shop’s clattery confines, its walls ornamented with photos of happy customers, including President Barack Obama, who has a honey-Cuban sandwich named after him there; at the swoopy diner counter of La Teresita; amid the blue-collar crowd who line up at Brocato’s off I-4; with the charming waitresses at West Tampa’s Arco Iris; at the unassuming Gio’s Cuban Café on MacDill; at the Ybor pub/restaurant Stone Soup Company; and at the butcher shop Boozy Pig, which makes Huse’s favorite Cuban. And many other places.

If you’re looking for someone to tell you what “the best” Tampa Cuban is, I suggest you attend the Cuban Sandwich Festival in Ybor this April. But having appreciated so many Cubans in the city where I was born, I began to wonder if something more was at play—with the Cuban, or with me. Because, see, the Tampa Cubano seems to mix especially well with its surroundings, with the people. Over the course of more than a hundred years, the city of Tampa—independent of Miami or New York or anywhere else—has embarked on a collective and successful quest to create a lunchtime hunk of sustenance to answer specific, geography-inspired queries:

What sandwich would taste good in this blazing sun, or in the blackness of an afternoon thunderstorm? What dish would one serve to downtown bankers and lawyers that would also mingle with chicken and yellow rice, garbanzo bean soup, plantains, or papa rellenas? What goes well with both Gulf saltwater and Central Florida swampland, spring’s sweet orange blossoms, and Ybor’s cigar-smoke bouquet?

The Tampa Cuban is pulled from the air and the water and our desires. In short, that’s why Danny puts up with unbearable heat, reptile run-ins, and yellowjacket attacks. The bakeries need him. It’s part of a larger community pledge to abide by traditions—to gather the palmettos to score the bread.