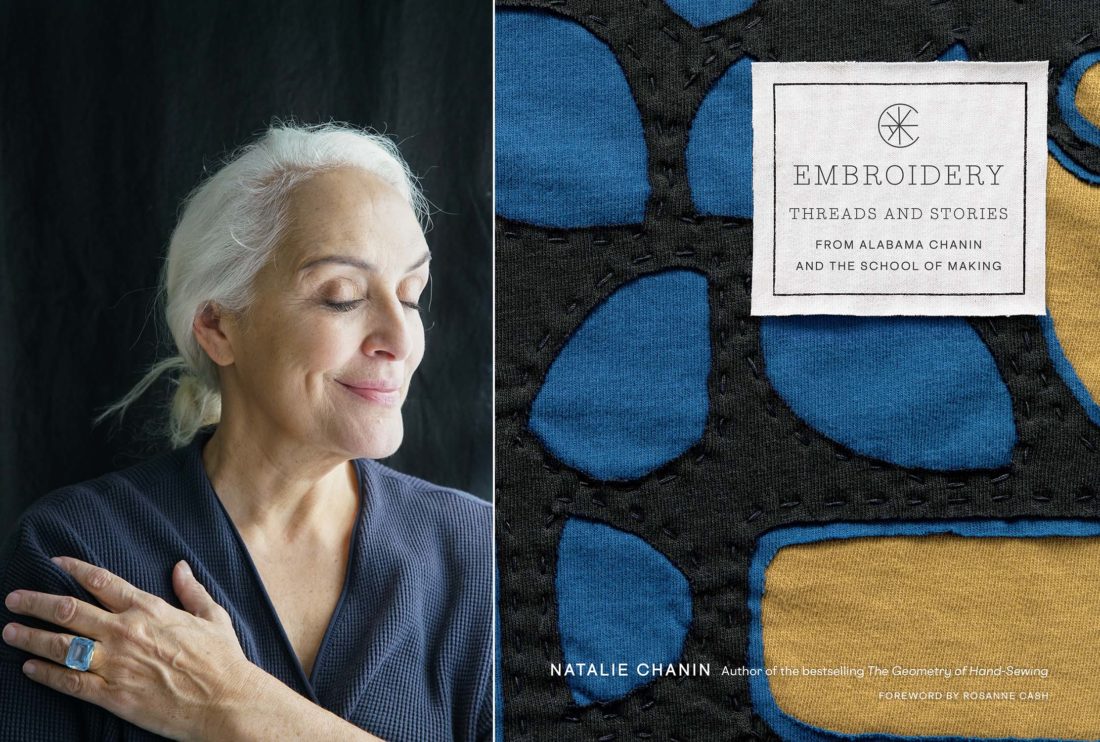

From her perch in Florence, Alabama, Natalie Chanin sees a beautiful view; the landscape of her youth, which she returned to in adulthood to launch her clothing and lifestyle company, Alabama Chanin, in 2000. The origin story of her business dovetailed with a re-awakening for her life that involved a move from New York that connected her back to the textile traditions of the Deep South and showed her the courage that was bubbling inside her. In her beautiful and personal new book, Embroidery: Threads and Stories from Alabama Chanin and the School of Making, Chanin describes not only her company’s journey, but the personal revelations she’s stitched together along the way.

“Last year, Alabama Chanin celebrated our 21 Years project—chronicling our twenty-one years of work in sustainable design and textiles,” Chanin says. “This was an important milestone for our team and the work we’ve been quietly putting out into the world for the last two decades. Embroidery is a collection of stories about my journey home, creative process, cotton, community, artisan-work, and design.” We spoke with Chanin about the new book, advice she’d give her younger self, the events she’s planning across the country this fall, and what she thinks about the current trend of old quilts becoming clothing. She even shared a few excerpts from the book.

You write about your family history of quilting and seeking out quilters who knew your grandmothers. Tell me more about what that meant to you to return home.

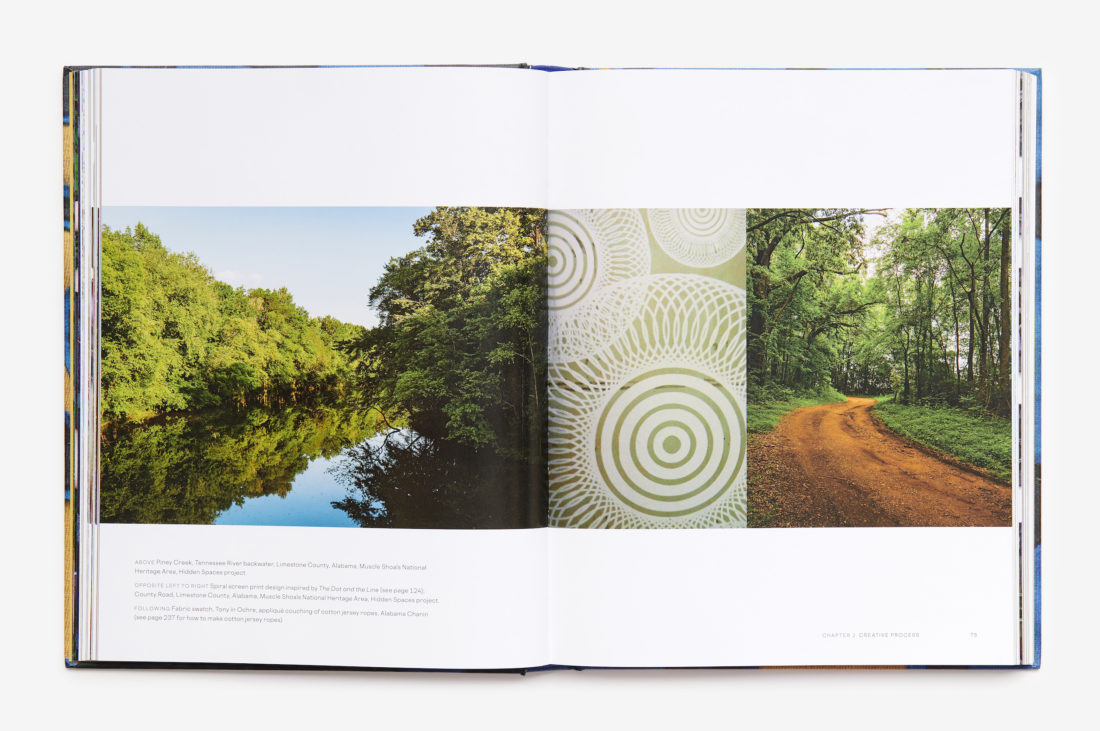

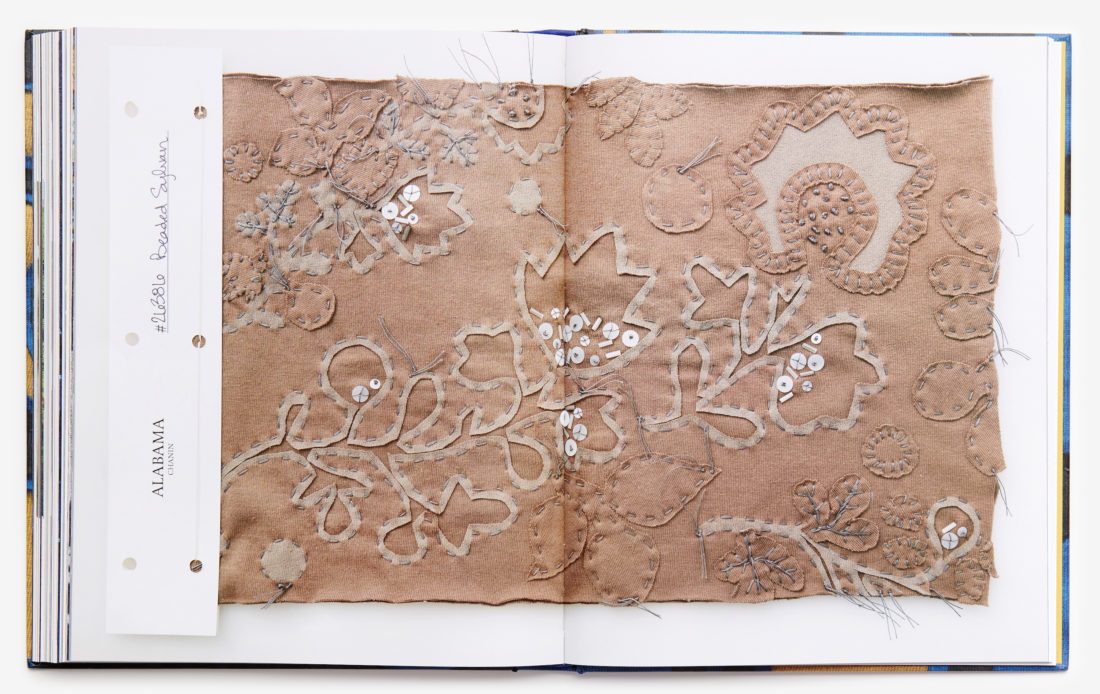

My parents were so young when I was born; consequently, I spent lots of time with my grandmothers and have so many deep and beautiful memories from that part of my life. When I first thought of returning home, a forgotten part of my childhood emerged, and I began to dream about the rivers, woods, and people of my childhood. Once I began to reconnect with these beautiful women I had grown up with, I was completely moved and inspired by their talent, connection to the land, and an undying respect for their community.

What do you wish you could tell twenty-year-old you? Thirty-year-old you?

There is so much. I remember myself in those decades as being filled with fear, uncertainty, and an overwhelming unsettledness. I wish there was a way to go back and soothe the younger me—showing her how to embrace life through fear, teaching her how to play with uncertainty in the creative process, and nudging her to tap into unsettledness as inspiration.

My life would have been easier; and yet, I also wonder if I would be who I am today if I’d come to know these important lessons at such a tender age. In the introduction to Embroidery, I tell a story of facing fear—swimming off the coast of a Venezuelan archipelago at the end of my thirties. After emerging from the water onto a little beach, I had a realization about fear and living:

I told myself that I’d never be afraid again. I can’t say that I live or have lived every day without fear, but I began to see my life with the same sense of connection and courage I felt standing on that little beach. That moment was the beginning of Alabama Chanin and the School of Making.

Every step I’ve taken since that day has led me closer to home. Twenty-one years later, I sit here and think that this may not be redemption, but it looks like something that veers in that direction. Creative process is filled with fear and vulnerability, and yet, we rise up every day and keep making stories.

Tell me what it’s like to craft with your granddaughter these days.

A few weeks ago, my granddaughter, Stella, and I were designing and sketching together. We were drawing ideas for a show she envisioned and, when our drawings were done, she commented that mine was so much better than hers. I laughed and reminded her that she is ten years old and that I started design school forty years ago. We had a big laugh and she replied, “I guess you are right.”

In Embroidery I write: In my twenty-one years of working as the designer and creative director of Alabama Chanin, I’ve been questioned more about creative process and inspiration than any other single theme or idea. There is a famous story about the poet Ruth Stone catching the end of a poem as it passes through her body and, in that moment, transcribing the poem to paper in reverse order, from the last word to the first. This is a dream creative process, but, unfortunately, not one that I’ve ever experienced. Creating can be painful and vulnerable, or at least slow, which explains the constant search for ‘inspiration’ or ‘secret sauce’ or perfect setting—anything at all that will simplify and expedite the process. But in my experience, there is no shortcut; however, if I keep showing up, day after day, the work and inspiration arrives. I make a rule with myself that I will show up in fear; I show up in love, and when it rains, and when the sun shines, and when I’d rather be a thousand other places but here. I show up in doubt, and grief, and joy. I show up to do the work—even if the work is one sentence or a single board or a stitch. Showing up is a commitment to something greater than ourselves; showing up is the commitment to ourselves. As Rollo May puts it in The Courage to Create, ‘Commitment is healthiest when it is not without doubt but in spite of doubt.’ Doubt doesn’t go away with time, but it does go away some days. Either way, we still show up.

What do you think about the latest resurgence of quilts in fashion?

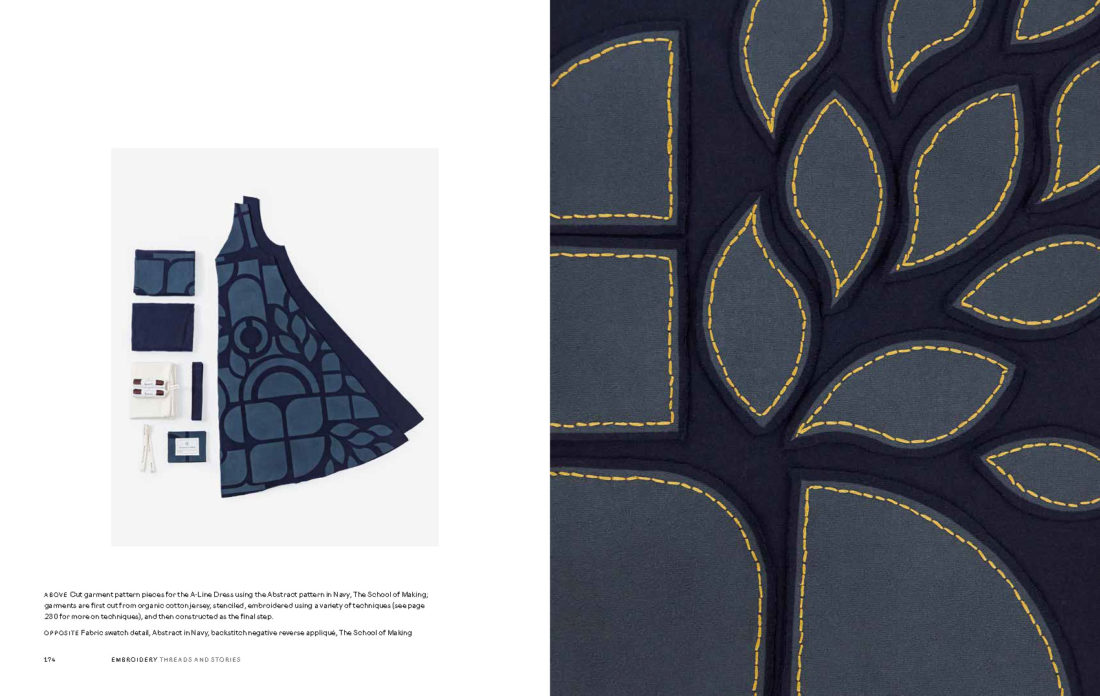

I believe we are circling through a time in our evolution where we have a visceral need to connect our lives to making—and consuming products that have meaning for us and the world. The resurgence of quilts in fashion is one of the ways in which we connect to a past ideal of what making means. I’m excited for this, but even more excited about what the next steps will be for creating artisan-made goods that truly enrich us as designers, makers, and consumers.

Tell us about any projects in the South that are bringing you joy and hope.

Right now, I’m incredibly inspired by the work we’re doing with Project Threadways [a nonprofit organization that records, studies, and explores the history of textiles]. There are so many young and brilliant public historians who are working to collect and document textile histories across our region—in order to tell these stories in a more truthful, inclusive, and beautiful way. These scholars are honoring the past and, at the same time, creating new pathways for a sustainable future.

G&G recently covered someone you know well, the designer Erin Reitz…Can you shout out some more of your colleagues and friends whose work you admire?

Yes, Erin Reitz’s company, E.M Reitz, in Charleston, South Carolina; Katherine Hayes of Dreambox Jewelry in Nashville; Phillip March Jones of Institute 193 in Lexington, Kentucky, and MARCH Gallery in New York City; Conley Averett of Judy Turner in New York City.

What kind of events will be part of this book, and do we know any dates/places yet?

Details and times here. We have events confirmed in Detroit, Raleigh, Atlanta, and Charleston.

What do you hope your legacy will be?

It has been really exciting for me to work with this new generation of designers, makers, and creatives. I see a different kind of attitude and commitment to creativity, community, and ethics as a groundswell. I believe that Alabama Chanin, the School of Making, and Project Threadways—my legacies—are being tended by strong and able hands that will continue to create meaningful impact in the coming decades.

CJ Lotz Diego is Garden & Gun’s senior editor. A staffer since 2013, she wrote G&G’s bestselling Bless Your Heart trivia game, edits the Due South travel section, and covers gardens, books, and art. Originally from Eureka, Missouri, she graduated from Indiana University and now lives in Charleston, South Carolina, where she tends a downtown pocket garden with her florist husband, Max.

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with Bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book. All books are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.