Arts & Culture

Forrest Gump Turns Thirty: An Oral History of the Unexpected Blockbuster

Three decades after the release of the film, a collective story of its making reveals Gump still looms large in the lives of the stars and the locals who helped turn a movie no one wanted into an Oscar-winning smash

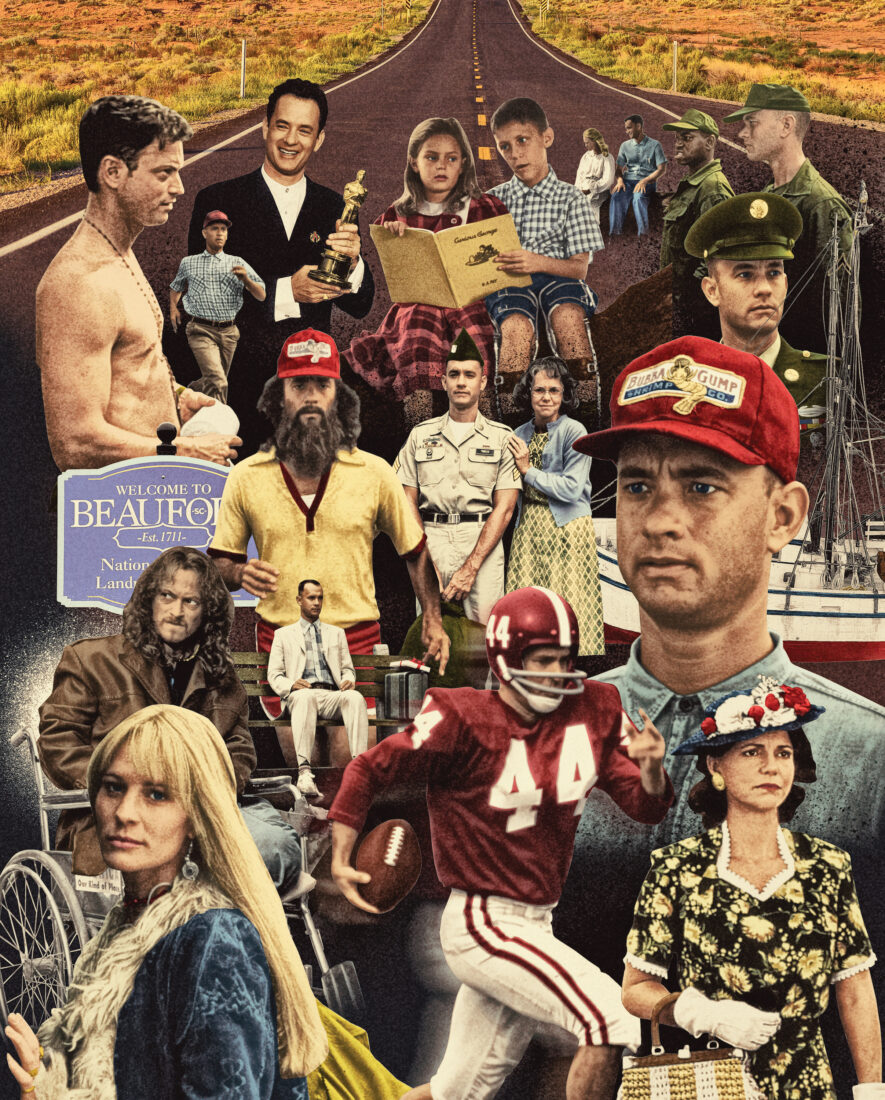

This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of the release of Forrest Gump, a film Southern in its setting and sensibility, and global in its resonance.

The movie sprang, of course, from the eponymous 1986 novel by the late Winston Groom, who was a Garden & Gun contributing editor. When asked how the film version affected his life, his favorite response became “I upgraded to a better brand of toilet paper.”

That’s because upon its release on July 6, 1994, Forrest Gump—directed by Robert Zemeckis, and starring Tom Hanks, Gary Sinise, Robin Wright, Mykelti Williamson, and Sally Field, among others—took the world by storm, earning nearly $700 million at the box office and six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor, for Hanks.

Three decades later, the film remains a classic, maintaining its winning, heartening, and indelible place in American culture. But its impact on the people who took part in its filming, which happened primarily in Beaufort, South Carolina, may offer an even bigger legacy. In the following oral history, both the main players—including Groom, with words from a previous G&G interview—and the everyday folks who brought the movie to life tell the story of its making and its meaning in their own voices, their lives forever changed by their time on set.

The Genesis

Winston Groom came up with the idea for his novel while on a trip home to Mobile from Manhattan, where he was living at the time.

Winston Groom, novelist: I went home to see my dad. We had lunch in a restaurant downtown, and he started reminiscing about his childhood. In his neighborhood, there was a boy who was what you would call slow-witted, and the kids would tease him and chase him and throw sticks at him. Then one day this truck arrived outside of the boy’s house, and out of it came this big piano. And within a few days, this beautiful piano music began wafting out of the windows. It turned out that this boy was some sort of musical genius. The kids stopped picking on him then and took him under their wings. [The show] 60 Minutes had also recently run a story on what was called the savant syndrome, where a person could barely tie his own shoes but could perform remarkable math or memory problems. I went home and started to make notes on that conversation, thinking I might use it as a scene in a book. By late that evening, I had written the first chapter of Forrest Gump.

Groom finished the book in six weeks.

Groom: I’d sit down in the morning and say, “What’s he going to do today?” And I think the thoughts flowed from what I call the lizard brain, which is down in the back of my neck, and straight onto my ten fingers at the keys…I sent it to my agent and waited a day or two. The phone rang, and all I heard was the sound of laughter. My agent said, “I love it.” He sold it pretty quickly. One great thing about the book is that it got me home. It made me want to leave New York and hang with my friends in Alabama.

Wendy Finerman, Forrest Gump producer: I got Winston’s book in galleys a year or so before it was published. It got under my skin. When I optioned it, I was twenty-four.

It was about a ten-year battle to get it made. We had a lot of rejections. Rain Man came out during development, and people said, “There can’t be two of these; there can’t be two phenomena like that.” But I was not going to give up on it.

Warner Bros. eventually bought it. They had it for a number of years. An executive named Kevin Jones was there. He loved it. The script had gone through a number of different phases, and we just couldn’t get it.

Then Kevin went to Paramount. This movie was his project. He knew that Warner Bros. wanted to make a movie called Executive Decision, which Paramount owned. So he said, “What if we do a trade?”

Paramount indeed traded Executive Decision, which ended up starring Kurt Russell and Halle Berry, for Forrest Gump. Executive Decision came out in 1996 and grossed $122 million at the box office, on a budget of $55 million. Forrest Gump also had a budget of $55 million but reaped $678 million.

Finerman: There was a new regime at Paramount when Forrest Gump got there, with Sid Ganis, Brandon Tartikoff, and Sherry Lansing in leadership roles.

Sherry Lansing, chairman and CEO of Paramount Motion Picture Group from 1992 to 2005: When I became chairman, Forrest Gump was already at the studio in development and a second draft had already been written. When I read it, I was excited and cautiously optimistic that, if we brought the right elements together, this was a movie we would be thrilled to make.

Finerman: [Screenwriter] Eric Roth, Tom Hanks, and I had worked together, on The Postman, so we decided to develop this, too. Eric went back to the beginning with the script and didn’t use any previous versions. He came up with the idea for the feather at the beginning and end of the movie. When the script was ready, we gave it to Sherry. She had some notes. Then Bob Zemeckis and I went out to dinner, and he was in.

Groom: I was at Elaine’s [the erstwhile New York City hangout] one night. A guy turns to me and says, “They’re making the movie about your book at Paramount.” I told him, “That’s news to me.” The guy told me Paramount had gotten it from Warner Bros. I couldn’t believe it. I found out Eric Roth had done the screenplay and Bob Zemeckis was directing and Tom Hanks was starring. I had not seen Hanks in anything other than Bosom Buddies. So I went to see Philadelphia, and I realized he was a really fine actor. Everything went fast from that point.

The Setting

Finerman: I moved to Beaufort for four months. We all did—Tom, Robin, Bob, Gary, Sally. I’m from a Southern family, so I was comfortable there. Going on location in a place like Beaufort is different than going on location in, say, Chicago. There weren’t many restaurants in town. We were all together, day and night. Tom’s and my kids would play hide-and-seek in his trailer. Robin had just had her second child, who was down there with her. Sally was so good with Michael [Conner Humphreys, who played a young Forrest Gump], this boy who had never acted professionally. She had her experience as a child actress to draw on.

It was tough filming. We needed to get a lot done in a short time. We all had our moments. I remember I was in the church while they were shooting the Hallelujah Singers scene and I just burst out, “My God, it’s so hot in here,” and everyone shushed me.

But it was so fun. We all had a great time. It really felt like we were a big family.

Gary Sinise, who played Lieutenant Dan: I’d never been to Beaufort. Forrest Gump was very early on in my film career. Just the fact that I got the role and had to get on an airplane to go shoot it was exciting.

I loved Beaufort. I was there the entire shoot, but also had preproduction time, so was there before the shooting, learning how to shrimp and doing a military boot camp to get ready for those scenes.

Marlena Smalls, head of Beaufort’s Hallelujah Singers, who played the mother of Bubba Blue: I don’t think the average person understands the magnitude of what happens when a film crew comes to your town. Paramount created a city within a city. They had their own electricians, water folks, construction crew, billing department, everything. I found that so fascinating, because you don’t think about the care and preparation that go into it all when you sit down to watch a movie.

Tom Hanks was wonderful. Some of us had dinner one night at one of the restaurants in town. I watched him as he came in. He was so marvelous at making everyone in there comfortable. He walked around to each of the tables and said hello and asked how the food was. By the time he was finished, no one bothered him during his meal.

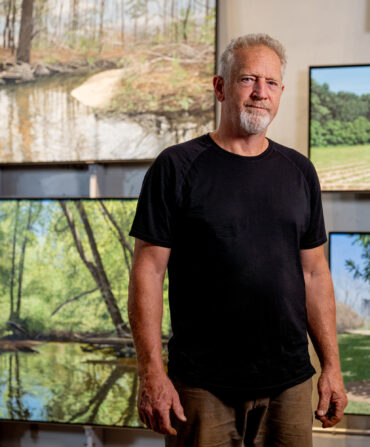

Jim Passanante, set painter: I was in California and got a call that they needed some help. I brought all of my equipment down there. We painted everything you saw in the movie—the props, the cars, the boat, the trees. I had worked with Zemeckis on Back to the Future and knew how he did things. It was nothing out of the ordinary, kind of calm, actually, except for the hurricane we had during the filming. It didn’t hit us directly, but we had to cover up all of the windows and doors to keep the set safe.

The Gump House

Much of the movie takes place at the Gump house, set in fictional Greenbow, Alabama. In actuality, the property lies in Yemassee, South Carolina, some twenty-five miles northwest of Beaufort, along the Combahee River—and no house existed on it, just a lodge used for weekend hunting.

Ann Kulze, daughter of the late Harry Gregorie, a doctor and co-owner of the property: My father and two partners owned what was then known as the Bluff Plantation. The property was about three thousand acres.

The story goes like this: It was a Sunday and my parents happened to be at the small lodge on the property, right at the end of the driveway lined with the big oaks. There was a film scout who had been driving around the area. We had cows at the time, and she had seen one in the road and had stopped by because she was worried that it had gotten loose. My parents were very welcoming and friendly people. They invited her in. She must have liked what she saw. She explained her interest in the property and the plans for the movie. The movie people called later and leased the property. My dad got the okay from the other owners.

My parents knew who Tom Hanks was and were made aware Bob Zemeckis was a big director. They were superficially aware that this was possibly a big-time movie.

I visited the property just before the movie people showed up, and then went home to where my husband and kids and I were living in Georgia, and then came back up a week or so later. And there was a house on it! Paramount had flown in artisans from all over the country to build the Gump house. They finished the wood so it looked like it had been there for a hundred years.

My mom knew there was going to be a wedding scene, and she suggested the place for one, right on the lawn by the river underneath the canopy of oaks. That’s exactly where I had gotten married.

After the movie people were finished, there was some discussion among my father and his partners about keeping the house. It wasn’t up to code, but they talked about bringing it up to code. The decision was ultimately made to not do it. It became apparent that it would become logistically complicated with three families who all had kids who were getting older. Later on, the partners decided to break the property up into three different parcels so that every family would have its own piece.

That oak tree that plays a big role in the movie was on our property, too, the place where a young Forrest and Jenny climb, and where Jenny is eventually buried. It’s our family burial ground. We spread my sister’s and father’s ashes there.

The Boat

Miss Sherri, a shrimp boat owned by the late Beaufort fisherman Jimmie Stanley, became Jenny, the boat Forrest Gump buys to shrimp with Lieutenant Dan.

Jimmy Stanley, son of Jimmie (yes, their names are spelled differently): We owned the boat for nine years before Paramount came. I was working on it. Sixteen years old, the youngest guy out there shrimping. The Paramount people went through all the boats in Beaufort. They picked ours because the sides were wide enough that they could roll cameras down it.

Tom Boozer, a Lowcountry woodworker and model maker: That boat was completed in 1973. It wasn’t made from a mold or a plan or a factory, like most shrimp boats. It was one of a kind, with a very sharp bow and turned-up nose.

Stanley: We took people from the movie out shrimping, showed them how the boat worked and how to put up the outriggers and put out the nets. We told them that we dragged for four hours and checked the try net every fifteen minutes. One of the men asked me what I did when waiting to check the net, and I told him that I climbed the ladder and sat up on the mast and watched the wildlife, the sharks swimming by and the shrimp jumping. They decided to put in a pulley system and a chair so they could have Lieutenant Dan sit up there.

We took Hanks and Sinise and Mykelti out dragging once. Sinise stayed in the back and asked me questions. Hanks and Mykelti stayed inside with Dad. We showed them how to pull in the nets.

One time, Hanks, Sinise, and Mykelti had dinner with us at my grandparents’ house. My dad told Mykelti about all the different shrimp dishes. He was a cook. I’m not sure if that’s where Mykelti got the idea for Bubba listing all the different things you can do with shrimp or not.

I was on the boat during filming a bunch. When the boat ran into the dock. When the news crew showed up to report that Gump’s boat was the only one that had survived the hurricane. The movie people kept radioing me to tell me they could see me, and I had to get out of the shot. The hurricane scene was crazy. They had four barges set up around the boat. One had a jet engine blowing on us. They had water cannons on the other ones. They had a sprinkler system above us. People on the sides were pulling on the boat to rock it back and forth.

Boozer: When the movie was over, Jimmie asked me to do some models of the boat. My wife and I spent about five days on it, measuring it and getting the details to make sure it was all totally accurate. I built Jimmie the first model, and then made one for the son of the man who built the boat in 1973. Then I made one for my wife. She had to have one. We took hers to a maritime show, and then I started getting orders like crazy. I’m on my thirty-first model now.

Stanley: We shrimped the boat for about another two years after we got it back from the movie people. And then Planet Hollywood called and bought the boat.

Drew Chipchak, former employee, Sanford Boat Works and Marina in Sanford, Florida: Planet Hollywood contracted us to move the boat from Beaufort to the Orlando area, where they were. My boss sent a pilot and a mechanic. I asked to go along just for the experience. I was in my twenties, and it sounded like an adventure. We rented a car and drove up there and met the owner. You could tell that people in town were kind of sad that the boat was leaving.

We left in the morning. We went by the ocean. We had to go like six miles an hour. The boat was pretty beat up. We entered the St. Johns River, where we had to lower and raise the outriggers at every bridge. We got to Sanford in a few days.

We did some repairs on it because it had been sitting in the water. A TV station came by one day. Planet Hollywood put a bench with a dummy of Forrest Gump sitting on it. The pilot was also a woodworker. He took the Miss Sherri placard off the side and put up one that said Jenny. I still have one of those placards hanging on the wall in my house.

Planet Hollywood parked the boat in a lagoon as a tourist attraction until 2013. During a renovation, it was moved, and has never been displayed publicly since.

Susan Flower, director of public relations, Planet Hollywood: We no longer have the boat and don’t know where it is.

The Shrimp

On September 7, 1993, Paramount bought 4,984 pounds of shrimp, forty-five baskets of ice, and a used shovel from Gay Fish Company on St. Helena Island, near Beaufort, for $15,125.30. A week later, the studio purchased another 1,141 pounds—at a nickel more per pound—and more gear, for $11,814.80. The filmmakers used the shrimp in the scene when Forrest and Lieutenant Dan finally have success as shrimpers.

Charles Gay, owner, Gay Fish Company: It was a good-sized order, all right. They were using our shrimp boats, so it made sense. They were pretty cheap, though. They wanted me to sell the shrimp after they used them to get some money back, I guess, so I sent the shrimp to a cat food place. They called and said, “Charles, what in the hell did you send us? This stuff is rotten.”

The Photobomb

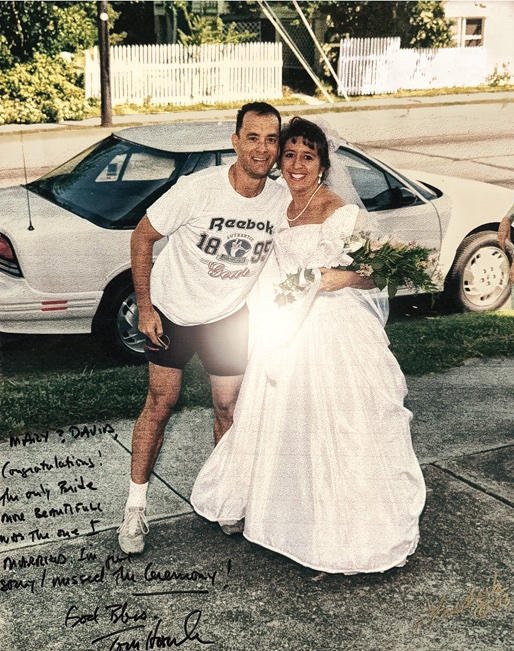

Forrest Gump was filmed from August to December 1993. The wedding of Mary Dunning and David Chapman took place on September 11, 1993, at 4:00 p.m. at Carteret Street United Methodist Church in Beaufort.

Mary Chapman: Just before four o’clock, I was coming around the side of the church with my bridesmaids, about to head inside, when we heard a car blow its horn. We waved. We didn’t know who it was. When we got to the front of the church, the same car pulled up, and out hopped Tom Hanks. He was in workout attire. “Hey, my name is Tom Hanks, and I wanted to say congratulations,” he said. He gave me a quick hug and started to walk back, and I said, “Wait, let’s get a picture.” Our photographer took a photo, and Hanks gave me a little peck on the cheek and jumped back in the car. My bridesmaids were hooting and hollering.

We were on our honeymoon when my parents called and said that Hanks’s driver wanted a copy of the photo for Hanks. So when we got back, we printed out two eight-by-tens and signed one and gave them to the driver. A week later, we got one of them back in the mail, signed by Hanks. David and I live in Beaufort now. I was the original crashed wedding. Hanks has crashed several since then.

The Voice

Groom told Garden & Gun in 2019 that the voice coach for the movie called him one day before filming began to ask what Forrest Gump’s accent should sound like.

Groom: I sent her to Jimbo.

Jimbo Meador, a friend of Groom’s from Point Clear, Alabama: I talked to Jessica Drake, a dialect coach. She called me and taped our conversations. She said I had an unusual accent, a Point Clear one, that was different from even other Southerners’. They also used [as inspiration] the voice of the little boy who played a young Forrest Gump [Michael Conner Humphreys, who was from Mississippi]. But I talked to Jessica after the movie, and she said she used our tapes for Tom.

People have always teased me for how slow I talk. Lefty Kreh [the renowned fly fisherman] said they asked me to be on 60 Minutes, but couldn’t do it because it would have taken an hour and a half. Then he said, “You know, Jimbo has had a lot of different jobs in his life, but the one he failed most miserably at was being an auctioneer.”

Jessica Drake, voice coach: We did use Jimbo’s tapes. We took some things from Michael too. The way Forrest talks is a bit of a mash-up. The accent is all Jimbo. From Michael, we took the vocal pattern. He did something called upspeak, where every sentence sounds like a question, which seven-year-olds sometimes do. We liked it because it was a tricky balance with Forrest Gump to not make him seem pathetic. You have to be part of his journey and go along with him on it and not feel sorry for him all the time, and this was a way of doing that by making him sound like a kid.

The Actors

Sinise: My agent sent me the script. The year before, I had produced and directed and acted in a movie version of Of Mice and Men. I was told that Wendy and Bob had seen it and wanted me to come audition.

I had been actively involved in various Vietnam veteran initiatives for a full ten years when I got the script. I had Vietnam veterans in my family—my wife’s two brothers and her sister’s husband—and loved Lieutenant Dan and his story, so I very much wanted to audition for it. My audition was in a conference room. Wendy and Steve Starkey [another producer] and Bob and Eric were on one side, and I was on the other, sitting in a chair, pretending it was a wheelchair. They told me they liked me, but that they were seeing a lot of people for the part. So I went and auditioned for a couple of other things and got close to getting them, but thankfully didn’t, because Bob and Wendy came back to me and offered me the role in Forrest Gump.

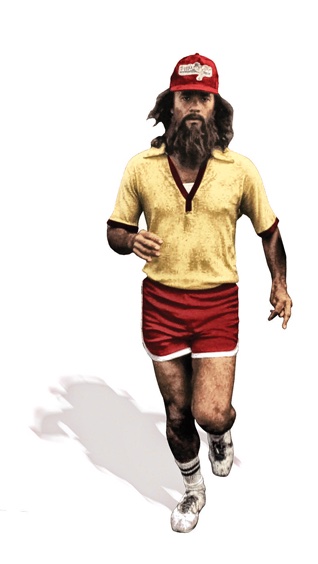

My first scene was when Tom jumps off the boat and then the boat crashes into the dock. Then we shot all of the Vietnam scenes. I had to have a wig because I went back and forth between the short hair shots in the war and long hair shots after.

Brett Rice, who played Forrest’s high school football coach: This was early in my career. I was living in Florida and shooting a TV show when my agent told me he had a part to read for a movie called Forrest Gump. The description was a high school football coach, standing with Bear Bryant [the legendary Alabama football coach].

I did my audition. As I spoke my lines, I looked from right to left following Forrest running on the field. The casting director told me I was awesome. “Why?” I asked. “Because you were the only person who watched Forrest as he ran,” he said. I knew football. My first role was actually in a Bear Bryant movie.

Jessica [Drake] came into the dressing room when I got on set and told me to do my lines, because she said I needed to have a Southern accent. I said, “Seriously?” I said my lines and she said, “We’re good.” I was born in Chattanooga and raised in Atlanta.

We couldn’t shoot my scene for a week, because it was raining. When I finally got on set, Zemeckis sent Sonny Shroyer [who played Bryant] and me into the stands to do our lines. We shot for about two hours. The whole time, Tom and his brother were running up and down the field. I worked with Tom later on, on the movie Sully, and I said, “Man, you ran a lot during the shooting of that scene.” He said, “I didn’t mind. My brother was doing the sprints.”

Marlena Smalls: The Hollywood producer Joel Silver had a property on the Beaufort County line. The house had been built by Frank Lloyd Wright. Joel had events there, and he started inviting me out to sing for the guests, Hollywood-ites like Bruce Willis and Demi Moore and Sylvester Stallone. Robert Zemeckis was at one of the events.

At the time, there was a list of South Carolina people to know whose names and numbers [state officials would] send to newspapers and magazines and movie people when they came to town. I was on that list. When the movie people came in, they called me and asked me to help them with the music, and then to find Black faces for parts.

One day, the casting director Ellen [Lewis] called me to the office to read for the part of Bubba’s mom. It was lunchtime, so I didn’t take it too seriously. I thought she was just filling time. A couple days later, the music director called about the choir scene. I thought, Okay, all righty. And then Zemeckis’s office called [about Bubba’s mom]. Now, I’m a musician. I would have been more excited if Sony Records or Zubin Mehta [the conductor] had called me. Then Zemeckis got on the phone and asked me to do the part and explained the money, and I changed my position, as anyone would do.

My first day, I went to makeup, and I walk in and there’s Tom Hanks. I didn’t speak to him, because what would I say? He was reading the paper. He put down the paper and said, “Well, good morning, Bubba’s mom.” It broke the ice.

That scene where I pass out when Forrest hands me the check [for Bubba’s portion of the shrimping proceeds]? I did that. No stunt double. Now, I didn’t have a slip on that day, just black panties. And I was surrounded by all of these men. When Zemeckis asked me to fall down, I tried it several times, but it wasn’t working. They put a mattress behind me. I wasn’t falling right. He started to get a little impatient and said, “Why can’t you just fall down?” I told him that I didn’t have a slip on. And he said, “No one here is going to be looking at your ass. Just fall.” So, finally, I just let it go.

For the choir scene, we recorded the singing at First African Baptist. Hanks was there when we were singing, and he joined us. He wasn’t supposed to, but he did. We filmed the actual scene at a little church near Yemassee, in Hampton County.

Stevie Griffith, who played Forrest’s Vietnam platoon mate Tex: I was living in New York, acting, and then I moved to Atlanta because there was cool stuff happening there. My agent told me there was an audition for a Tom Hanks movie. Hanks wasn’t that big back then, but my cousin told me I better go. They flew us to Savannah for the audition. It was a Southern movie, and I had grown up in Greenville, South Carolina. I got the role.

They had a half dozen Vietnam veterans there to train us, and Captain Dale Dye, a vet who had advised Oliver Stone for Platoon. They took us out into the thicket on Fripp Island and dropped us off. We were there for three days and three nights. I slept in a foxhole with Mykelti. We were both big guys. We were still digging out our foxhole, trying to make it big enough, while everyone else was eating their MREs.

They wanted us to get into character. They attacked us in the middle of the night, blowing up these small explosives that were covered in peat moss that would fly everywhere. It was all well planned. We weren’t going to get hurt. But it was chaos and misery, and no one slept. The day we came out of the jungle, they put us on film. They wanted that thousand-mile stare.

The greatest day of my life as an actor was the filming of the scene when Forrest finds me in the ravine. “There was this boy laying on the ground” was his line. Tom and I had to sit there all day, waiting for the golden hour to shoot. At the end of shooting, he signed out and was walking away, and then he came back to tell me that I had done a great job that day. That meant everything. His generosity. That’s Tom Hanks.

Another day, we were finally ready for a rehearsal of the scene where Forrest picks me up and takes me out of the jungle, when the planes start dropping bombs. We were just standing around and at one point I started to sing, “Burn, baby, burn.” And I heard someone behind me sing, “disco inferno,” the rest of the line. It was Hanks.

When it was time for the scene, Tom asked the crew, “You had to pick the tallest guy?” Then he picked me up onto his shoulders. The stuntmen told me to grab his belt and push down to transfer the weight from his shoulders. Once I got up on his shoulders, Hanks said, “Roll it. I’m not putting him down.” The camera was ahead of us on a dolly track. When I’m ducking trees with my head in the film, that’s the real thing. At the end, we fell down a little ravine, off camera. Hanks jumped up and asked if I was okay. I said, “You’re the twenty-million-dollar man! Are you okay?”

Sinise: The Dale Dye military boot camp stuff was key to helping me settle into the soldier part of my role.

Afemo Omilami, who played the drill sergeant: I was living in Atlanta and went to the casting call. It had been twelve years since there had been a dynamic Black actor cast in a big movie, Lou Gossett in An Officer and a Gentleman. I was a long shot, not a New York or L.A. actor. But I fit the part. I grew up in Petersburg, Virginia. I’d done some work as a Union reenactor at the Civil War battlefield.

I had that scene where I yell in Hanks’s face and say, “Gump, you’re a goddamn genius!” I was nervous because it was Tom Hanks. He was cool. He calmed everyone else down. And he laughed when we first shot it. It is a pretty funny scene. We had to do a bunch of takes. By the time we did take six, we had the laughing out of the way. And then we had to do the second drill sergeant scene, and my voice was pretty much gone. Zemeckis said, “Let’s get this kid while we can get him.” We did that one much quicker.

The character of Lieutenant Dan underwent some changes during filming.

Sinise: I was sitting in a restaurant with Bob one night during the shoot, talking through the script. Originally, Lieutenant Dan got into his wheelchair and then went tooling around Saigon after his injury. I suggested to Bob and Eric that it felt too early in his injury for him to be doing that there. So we ended up saving that for the New York scenes, when he hangs out with Forrest.

Another time, Bob and I were talking, and I was thinking about the scene where Lieutenant Dan crosses the street in New York in his wheelchair. I started laughing when I came up with the idea of him having a taxi almost hit him and then banging on the hood of the taxi and saying, “Hey, I’m walking here!” just as Dustin Hoffman’s character had done in Midnight Cowboy. Bob liked the idea and took it even further. During the scene, he played the Harry Nilsson song “Everybody’s Talkin,’” which was in Midnight Cowboy.

Playing Lieutenant Dan helped support the formation of Sinise’s eponymous foundation, which honors and assists military veterans and first responders and their families.

Sinise: I was already very involved in supporting Vietnam veterans when I started filming Forrest Gump, with my wife’s family and as a young actor at the Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago. But after Forrest Gump came out, I got a call from an organization called Disabled American Veterans. They supported one and a half million veterans at the time. They asked me to come to their convention. I did, and they gave me an award for playing Lieutenant Dan.

It was very moving to be in a room with two thousand wounded veterans. I started becoming very active in the organization. Then September 11 happened, and I felt like I was teed up to help our service members who were going to Afghanistan and Iraq. I started going on USO trips and have been on hundreds of them. Thirteen years ago, I started the Gary Sinise Foundation. I invited Wendy to come to one of our events, when we hosted eighty wounded veterans, and she was blown away and has started supporting veterans’ organizations and is very committed to it.

The Aftermath

Stanley: The movie people invited us to watch the movie before it was released. We all went one night in Beaufort to an old movie theater that’s since been torn down. It was so awesome to see the boat on film, knowing that I was on there.

Gay: I guess I was proud of my shrimp being in the movie, but nobody probably knew they were mine. A shrimp is a shrimp.

Rice: I had no idea how this movie would do. It’s funny, because when I got on set and saw Tom’s haircut for his role, I was like, “What in the hell? What did I get myself into?” It never dawned on me this would go anywhere. Then I saw it in a theater in Atlanta with my mother and siblings, and I was gobsmacked.

Smalls: The thing that stood out to me about the movie were the lines “Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re going to get.” I parallel that with my view of America. It doesn’t offer you anything other than the freedom to do or be whatever you want. And it doesn’t guarantee that it will be easy. But you can do it.

Griffith: Hanks had this trailer he took everywhere. One day he went into it and came back out with these South Carolina Gamecocks hats and gave one to everybody. I’m a Clemson fan, so it’s hard for me to look at it. But I still have it. It’s signed by everyone.

Omilami: I have to pinch myself now, when I think about the movie. You could go your whole career and never be in a movie like that. It’s like Citizen Kane or Miracle on 34th Street, one of those movies that each generation discovers. I ran into Sinise when we were doing a TV series together. We took a Gump moment. Then I worked with Robin on a film called Hounddog, and we took our Gump moment.

I’m a blessed man. I’m still working. Forrest Gump? I love that guy. Thanks to him, my life has been a box of chocolates.

Passanante: I was the last person on the set in Beaufort, with the locations person. Everyone else went back to L.A. to do stuff in the studio. I restored a few things, like the dock where we painted Jenny. I restored some office buildings and turned the key and said to the locations person, “Hope to see you again.” And that was that.

I’d never been to that area of the country before then. I loved it. I took my wife down to Beaufort a little while later. I showed her Bubba’s house. She looked across the street at this falling-down house and said, “What’s that?” We ended up buying it. We still live here.

Groom: I was in Savannah, and I was watching the Today show, and they had an enormous ad for it, and I thought, Good God almighty. I realized they were spending a lot of money backing it. Boom. It opened. I didn’t go to the premiere in Hollywood. But Paramount gave me my own screening at the Carmike Theater in Mobile. I invited a couple hundred of my best friends. They had a tent outside with a bar and food. It’s funny watching your own stuff, to hear your words roll off the tongues of actors. But after about ten minutes, I got into it. They did a great job. I sat there stunned when it was over. Everyone sat very quietly and then stood up and cheered, and the mayor presented me with a one-sheet, the advertisement poster, sent by Paramount, that all the actors signed.

Sinise: Tom was nominated for an Oscar [for 1993’s Philadelphia] while we were filming, so he was a big movie star. And Bob had had massive success. We knew the elements were there for making a really good movie. But look at the story and how it was structured, with Forrest in the center of it, and then all of these other stories revolving around him. Lieutenant Dan is his own thing, and so are Bubba and Mrs. Gump and Jenny. The actors really didn’t interact with each other on set much. I had a little bit of time with Mykelti because of the Vietnam scenes. I had only one moment with Robin and Sally. The rest was with Tom. So I didn’t really know what the others were doing and couldn’t have predicted how it would turn out. It really wasn’t until the moment we all saw it together in a small screening room at Paramount. The principal cast members. My wife was there. Robin was there with Sean Penn. I remember when the lights came up after the movie and we all looked at each other with massive smiles because it was damn good, and everybody knew it.

And the movie still resonates. I see it when I visit troops in the hospital. They get excited Lieutenant Dan is there. It’s important that in the movie, Lieutenant Dan is okay in the end and moves on with his life. Prior to that, there were a bunch of Vietnam movies and you never thought the veterans depicted in them would be okay. Then Forrest Gump comes along and tells a different story, of a Vietnam vet who is able to stand again and is wealthy and is a businessman. It was unique. The whole movie is a great, classic story that’s well made and touches on so many different things. People who saw it when they were young now watch it with their kids. It’s like It’s a Wonderful Life, a movie people just keep coming back to, year after year. I’m proud to have been a part of it and thankful to have played Lieutenant Dan.

Finerman: I had no inkling that the movie would be a hit. I never feel that way about any movie. But I do throw my heart and soul into them, and I knew we had made a movie that came from the heart and had meaning. And that was the goal. It is the gift that keeps giving, not only as a movie, but because we continue to do so much work with veterans because of it, and try to bring them joy and recognition.

Paramount Pictures/Everett Collection; Chocolate box: winston – stock.adobe.com; collage: Everett Collection (15); Road: Tomasz Wozniak – stock.adobe.com; Sign: Bill Keefrey – stock.adobe.com; Shrimp: nathanipha99 – stock.adobe.com; Everett Collection (2); Mary Evans/AF Archive/Paramount/Everett Collection

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book.