Charles Thomas, the day you died I cradled your head in my palms with my face pressed to yours, our foreheads together, the two of us nose to nose, and I told you I loved you until you did not breathe again. I buried you in the winter when the ground was solid, and you, always the digger, would surely not have had it any other way.

That next morning, I carried stones from the base of the mountain to place at your grave. I did the work as if an act of meditation. I took my time is what I’m trying to say. I continue to take my time.

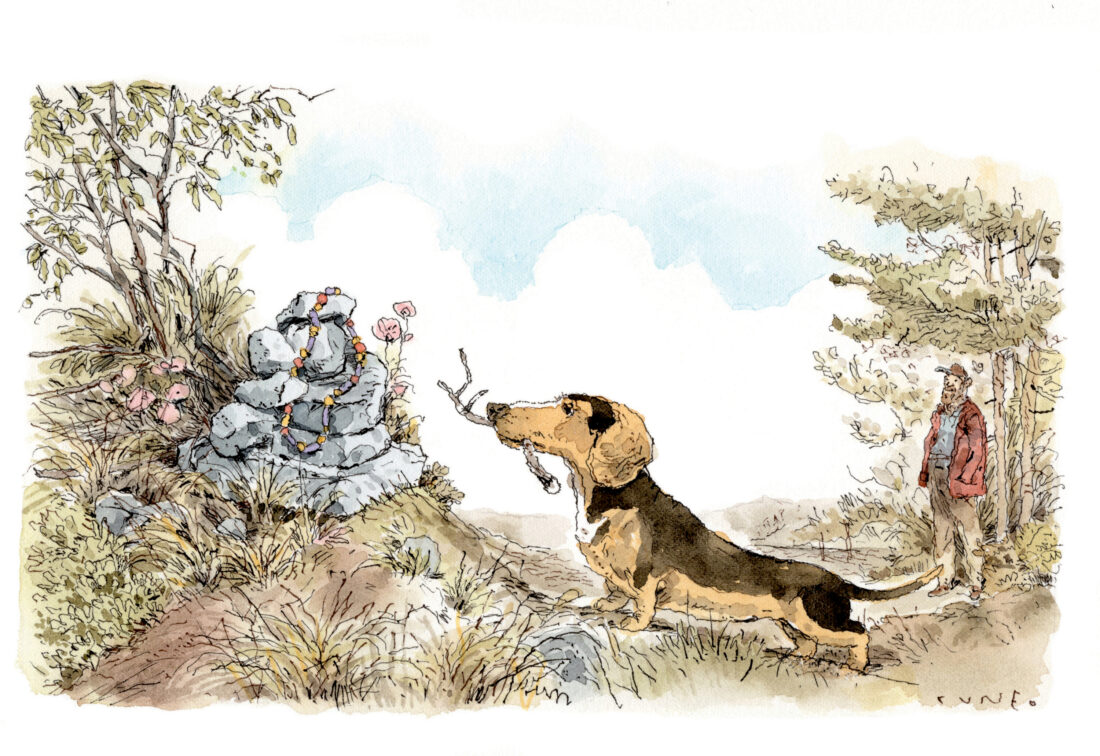

Slowly I’ve added to the stones. First it was a mala, prayer beads for you to count, because, just like me, you were always so anxious. Next it was pine knots like the ones we’d find on hikes, the ones you carried in your mouth like tennis balls. Over the past year, I’ve built a bed of green around the stones with puzzle pieces of moss gathered along the path from the house to your grave.

The other day I brought you a bouquet of cockleburs. If you’d been here, you’d have worn them. We’d have had to comb them out of your tangled white hair. You’d have hated us for it. I miss that. Oh, sweet dog, I miss that.

I have read that in Lakota tradition the grieving are to be revered, for they are the most awake, the most holy. There have been two moments in my life I have grieved with that sort of gravity. The first time was with my grandmother as I sat near her bedside while her eyes fixed softly on the end. She heard singing. She told me this. In that moment, I could feel the spell swirling around me, but I could not surrender to the absolute magic of it. I was too young and immature. I was not ready. I regret that.

The second time, sweet dog, was with you.

Your spirit hung around those first few days, just on the other side of some thin veil through which I could not see but feel. I know this for truth. I know this because I spoke to you and you responded with words you could not have said until you reached that place. And while some may say that’s crazy, I know you spoke to me because you said things I would not have said to myself. You said things that surprised me, that took me by the nape of the neck.

That first week, I knelt there on hands and knees for hours by the stones. My head was bowed, and I cried until I was empty. I told you things, some of which I’ll never tell another soul, but what I remember most is this: I told you that while I do not know how any of it works, if there were some way to come back, no matter how many lifetimes it might take, for you to leave and start that journey, I would be waiting and looking for you to find me.

In the years that led up to losing you, while we watched you inch then walk then sprint full on into the end, you surely heard us talk of the next dog. Your mother thought we could get one while you were still around. I always cut that conversation short. You were too old by then. It was too much to ask. In my mind, it would not have been fair. But you heard me describe what I wanted.

I wanted a dog that would track, a dog that could help the old men I hunt with each fall find the deer they’d shoot and lose. I didn’t want a dog that was gun-shy. I tossed around breeds but always seemed to settle on dachshund. My uncle who kept rabbit dogs when I was a boy had dachshunds in the house. My grandmother and grandfather on my mother’s side bred them. There was a history there, and you knew how important a history was to me. The only other requirement was that the dog be a rescue from these mountains.

Edie Munster is four months old. She has a dark, deep widow’s peak for which she is named, a black-and-tan face, and a white streak running from her throat down her chest that looks like you barreling headlong through the shadow and rust of autumn. She is a dachshund, at least in part, but like you a full-blown North Carolina mountain mutt. You were born beneath a trailer in Cherokee. She was born not far from there, just over the Big Laurel. I found her on Caney Fork staying with a woman who taught me poetry.

Edie Beans eats sticks like you. She has an equal disdain for bees. And if pressed on a last meal, she stands in full agreement that she would like a plate of my grandmother’s salmon patties, made with Double “Q” canned fish and soda crackers, fried crisp and gold the size of Morgan dollars. The first day I had her, I made her sit at my feet while I fired a rifle over her. She did not flinch. Unlike us, she seems to be scared of little.

One morning before the fog lifted, she led me up the hillside to your grave. She sniffed a circle around the stones, then climbed over them. I bit my tongue and tried to be patient. I was surprised by her gentle curiosity, even more when she lay down beside you and studied your grave piece by piece. A few days later, she carried a stick there and placed it on top of the stones. I did not know what to say when she did this. I still don’t.

That first week with her, I dragged a piece of beef liver on a ten-foot string through the oak grove down the ridge. I made the trail too long and too difficult. She was unsure of what was being asked, and multiple times I had to pick her up when she’d go off blood and carry her back to the start. Eventually, though, she got it worked out. She found what we were looking for.

By the third track, she understood exactly what I wanted the moment I placed her on the scent. By the fifth, we’d moved from beef liver to deer hide. She covered a hundred-yard trail with two hard bends, one straight up mountain, in a fuzz under two and a half minutes. All of this to say, she is a natural, and hopefully I will not screw it up.

The old men are excited about the work Edie and I have been doing. Willy the German sends me messages with instructions he translates from the Deutsch out of old books on training tracking dogs. He told me one way to get her to alert would be to cover food at the site so that when she finds it, she can’t get to it and begins to bark out of frustration. We’ll see how it goes. We’ll wait and see. But make no mistake, sweet boy, the old men miss you.

As I told you every day that you were here, no amount of time would have been enough. Not a million years. I’ve had dogs all my life, good dogs, all of them, and I have loved them all. But you were the one. You were my one, sweet boy.

Last week I finally cleaned out my truck to get it ready to sell. I had not moved anything in the two years since our final fall together. The towel covering the passenger seat was exactly how you’d left it. The horse lead we used for your leash was still on the floorboard. There was still water in your jug. When I started to clean your seat, I found your hair and it broke me.

I had to force myself to finish, and in the hour it took me to do it, I remembered a moment from my grandmother’s funeral. My sister and I were by the casket, and my sister could not let go of Granny’s hand. I tried my best to console her. I told her, “She’s gone.” I said, “That’s not her. That’s just a body.” My sister looked up at me and replied simply and beautifully, “Yes. I know. But I loved it.”

That’s all I know to say about the disappearing, sweet boy, the pieces of you that are gone and going away. Every once in a while, I still press your collar to my nose and try to smell your stink. I say that with a smile on my face and with tears in my eyes and with laughter that stutters out. Yes. I know. But I loved it.

David Joy, a twelfth generation North Carolinian, is the author of five novels, most recently Those We Thought We Knew (winner of the 2023 Willie Morris Award and the 2023 Thomas Wolfe Prize). Others are When These Mountains Burn, The Line That Held Us, The Weight of This World, and Where All Light Tends to Go. He is also the author of the memoir Growing Gills: A Fly Fisherman’s Journey and a coeditor of Gather at the River: Twenty-Five Authors on Fishing, a book that raises money for the CAST For Kids Foundation. Joy lives in Tuckasegee, North Carolina, with his dog, Edie Munster. Read more at his website.