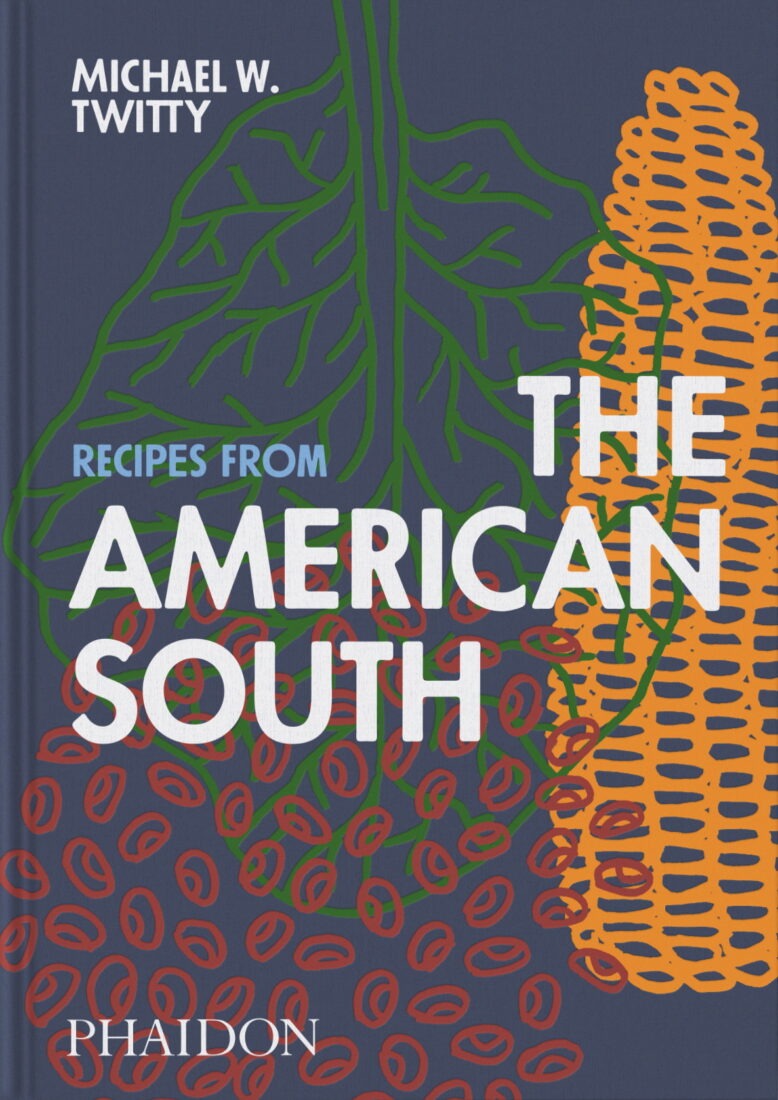

It’s been eight years since Michael W. Twitty’s James Beard Award–winning debut, The Cooking Gene, was released. Since then, he’s traveled the world for a comprehensive study of Southern culinary history through a global lens.

In his new cookbook, Recipes from the American South, Twitty contends that Southern food suffers from oversimplification. “Some Southern points of interest offer little jars of moonshine and canned ‘roadkill,’” he writes in the book’s introduction. “Others take home bags of benne wafers labeled in elegant flourishes, and heirloom vegetable seeds surround replica punch bowls at historic plantation homes or living history sites. The South itself is very much self-aware of the push-pull between competing stereotypes about Southern history and identity.”

Recipes from the American South offers a counterpoint that blends layers of history, cultural influences, and growing traditions without sacrificing a sense of heritage and place. Twitty chatted with G&G about the cookbook and shared recipes for Texas Caviar, Virginia Fried Apples, and Breaded Crab Chop.

Your book covers so much ground. How would you sum it up?

It is a scope of Southern food and cooking, and I’m aiming for it to not be either too expansive or too limited. I talk about how these recipes relate not just to specific cultures and moments of history, but also to moments of the life cycle, ecosystems. The fact that Southern food is seasonal is extremely important. Anybody in the South who has a garden right now knows this is one of the hardest-working times of the year. I don’t think there are many other regional cuisines in America where those ancient transitions of the four seasons are deeply part of the cuisine.

I’m working against a narrative that says, “They just made something out of nothing.” I mean, yeah, sometimes they did and did it beautifully. But some of these recipes go back thousands of years. We’re talking about the sum total of millennia—not just a couple hundred years—of the knowledge of the seeds of the plants, of the foods, of how to have spiritual relationship with that food.

One of the points you make in the introduction is that “the South is not a monolith, and no area can provide the breadth of the Southern story or fully set the Southern table.” How does that belief inform the cookbook?

This is one of the first cookbooks done by a solitary Black author that is a sweeping treatment of Southern food. Not just soul food, not just one version, but the whole thing, from Appalachia to East Texas to parts of Southern culture that often get ignored.

People think you have to be in Mississippi to be Southern. And I have to remind them, Mississippi didn’t show up until 1817…You have to talk about the French, the Spanish, the Germans, the many different varieties and ethnic groups from West Africa. You have to talk about the still-living Indigenous communities who are still exerting influence on the culture.

Several hundred years ago, there was a soup called caldo verde. And then it moved from the Portuguese through African hands and hands of people of all different backgrounds in the South and became collard greens. What’s even more powerful—even though I hate to admit it—is that those foods are going to be something very different in the South 400 years from now.

What was your experience like growing up in the South?

I was born and raised in Washington, D.C., but I have heritage from the South: middle Alabama, Virginia, and South Carolina. I remember how excited I was when my father took me down to see my grandfather in South Carolina—I could hardly sleep the night before. My grandfather taught me how to milk a cow, even though I got two drops out of that cow. I remember riding around in the truck with my granddaddy picking yellow watermelons. And I was thrilled. Every scintilla of my being was on fire. Little six-year-old me was helping my daddy read the map. It brings me to tears.

So for me, it was going to North and South Carolina with my father, and finally making it to Georgia and Alabama with my uncle, and going to those parts of Alabama where my grandparents are from, including Birmingham. I had the advantage of meeting the generation that knew their grandparents who were enslaved.

What do you hope people take from this cookbook?

I want people to mess this beautiful book up. I want there to be flour in it, I want hot sauce stains. I want there to be gravy fingerprints from children and grandparents.

It’s gorgeous and I’m very proud of that. The pictures of the foods themselves are so artful—not artsy, but artful. I said to my publisher, “Please avoid all red checkered tablecloths, and don’t give me messy food.” I don’t like it when I open up a cookbook and the food is strewn all over the table. Give me Sunday potluck–worthy food. I want it to be emotional and tell a story.

I want all Southerners to see themselves in this cookbook. I want this cookbook to function the same way the family tree in the back of the Bible used to function. I want people to see themselves, make their note, and pass it on to the next generation, because I really do believe in the power of our food to bring together all of our narratives and have us understand: We are one Southern family. We may be dysfunctional as hell, but we’re still a family.

You’re sharing three recipes with us today: Texas Caviar, Virginia Fried Apples, and Breaded Crab Chop. Can you tell us about them?

People think black-eyed peas and beans have to be sodden and overcooked, and I think the Texas Caviar is a really cool way to understand that we can gently cook them or use the canned version and have a bright salad. The name, of course, is fun in itself. And I had to make a point that Southern foods have nicknames. Anybody could say “black-eyed pea salad” or “vegetable salad.” We say Texas Caviar. We don’t say okra and rice, we say Limpin’ Susan. We don’t say black-eyed peas, we say Hoppin’ John. These dishes are family members, and so they have names like family members.

The Virginia Fried Apples was my grandmother’s recipe. The British Crown mandated that planters and farmers must grow apples and peach trees from the Chesapeake throughout the Lowcountry, which translated to later generations. Of course, apple country begins in the Piedmont and moves into the mountains. And I didn’t realize until my daddy and my grandmother told me that apples were fruit, vegetable, drink—the stuff of life. They were good as preserves, cooked, as cider. So the recipe is me looking at my grandmother’s way of cooking and going, “Oh, this was a staple.”

The crab chop is based on a recipe that’s just so damn beautiful from Peter S. Feibleman’s Creole and Acadian cookbook. It’s a crab chop, but it has a crab claw in place of the bone that you might see in a pork chop. It also was photographed against one of those old-school New Orleans plates that had the menu on the plate. I wanted to resurrect some of these recipes and give two or three versions. So, for example, there’s Maryland crab cakes, and there’s this crab chop. They’re similar but they’re dissimilar. They may not have the same fillers and ingredients or tell the same kind of story. It was really important to resurrect these recipes because I know that in time, good old-school recipes get forgotten because they’re way in the back of cookbooks and people aren’t looking anymore.