I will allow that my method of making beaten biscuits is peculiar and circuitous—one might say independent—and subject to the outright suspension of the so-called process to allow for musings mythic and legendary, and for the occasional metaphysical poke in the ether, but if you don’t mind taking the long way around the barn, as they say, I’ll tell you how.

First you need a deceased father who had the occasional good idea, though few came to fruition. And almost inexplicably, because ordinary food preparation of any extent ever remained shrouded in mystery to him, he needs to have squirreled away among his meager belongings a biscuit brake. Though as is fitting for this particular squirreler-away, it’s only a partial biscuit brake, glimpsed solemnly on a shelf, like a lonely set of upper dentures.

A proper biscuit brake, as it was designed in the nineteenth century, consists of the sometimes dangerous rolling apparatus of a wringer washer, preferably with a serviceable crank and adjustable rollers that can almost meet and pinch together tightly enough to squeeze the letters off a dolorous page from Leviticus. The wringers should be configured to spill the dough onto a cold slab of marble dusted with flour. Though it would only be a curious luxury, if the treadle of a foot-powered sewing machine were handy, you could affix a stray pulley in place of the crank and thereby connect the rollers and the treadle with a belt or a scrap of leather, and then you could tell your neighbors that your feet were sore from making biscuits, and that would turn a head or two. But that’s just the sort of entertainment you can get into with beaten biscuits.

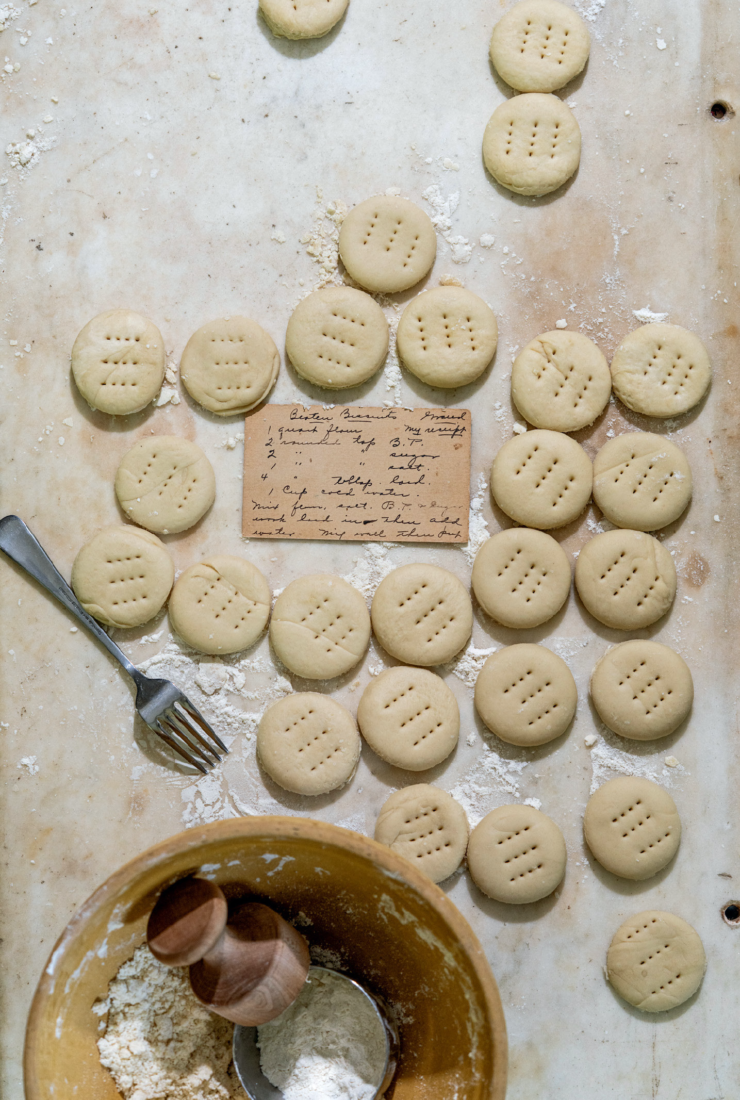

Next you need a great-grandmother with stout arms born about 1888. And the great-grandmother must be the sort to have left behind her a recipe, which she identified as “my receipt,” written on a rectangle of yellowed paper in the now aged and browned ink of a fountain pen. The receipt will call for a quart of flour, two rounded teaspoons each of baking powder and sugar, and one of salt, in addition to four rounded tablespoons of lard. Every time after the first “rounded” appears, it should not be surprising that the receipt records a ditto mark, ˝, in place of the actual word. And, of course, it will lastly advise, “Put dough thru kneader until dough is smooth and bubbles burst.”

And that explains the salvaged wringers from the old washing machine, famous eyesore or conversation piece on country porches, one no longer useful device scrapped to devise another one whose use will be revived one hundred years after the demise of the first, and lately reconfigured to allow the operation by a left-handed operator, which is you. The sound of bubbles bursting from the sedimentary compression of the biscuit dough is a kind of music.

The great-grandmother will be the sort as well who bore and yet survived every manner of hillbilly violence and corruption ever conceived either by apologists or accusers of the Southern mountaineers, she who witnessed and bore the knowledge that the men are the ones whose rashness and blood-feud-tainted code lead them to commit the violence and the corruption in the first pointless place, which only the women, if anyone, can redeem. And she did. She came through to the serenity of love that is the only thing worth the suffering and the only thing the next generation or the next will want or need as inheritance.

Then you will find yourself bewildered with the memory that as a child you often played with the same fountain pen with which she inscribed her receipt, one whose reservoir was as dry as an October cornstalk and whose nib scratched the coarse paper as if you knew letters and had something to say that required the labor and the rhythm needed to turn the pen into a musical instrument, as Orpheus of old tuned his lyre or Pan twisted his humble reed. The pen slept in a shabby drawer of refuse and old postcards addressed to “Kiddo” or “Sister” the great-grandmother kept in her room. You will need that memory recalled and now indelible in your mind many decades later, with the great-grandmother long returned to the earth, though the receipt survives, and so does the fountain pen, which one day in the search for meaning during a time of plague and pestilence you determine to refill with ink, and soon the nib glides to life.

By this point the circuit ensnaring the proverbial barn widens and snakes further into the ineffable labyrinth of time and locution, the very Logos, the bedrock undergirding articulate thought. Strangely enough (yet there must be in the dark mysterium a summoning voice to which your ear binds and determines itself to respond), you find yourself rereading the works of William Faulkner in order to—what? To broach, not to expiate, but to begin to fathom the founding sin of a nation, because violence of any measure marks its own moment but also leaves its mark to trouble and entangle the unimagined future, which is now.

As the reading mind and the written word find ever-closer commerce and consort with each other, you arrive at this from the final “Dilsey section” of The Sound and the Fury (1929). Dilsey, the Black cook who binds together the fraying strands of the white Compson family, discovers her teenage grandson, Luster, holed up in the Compson family cellar, trying to play the handsaw, an Orphic image if ever there was one: “He held the saw in his left hand, the blade sprung a little by pressure of his hand, and he was in the act of striking the blade with the worn wooden mallet with which she had been making beaten biscuit for more than thirty years. The saw gave forth a single sluggish twang that ceased with lifeless alacrity, leaving the blade in a thin clean curve between Luster’s hand and the floor. Still, inscrutable, it bellied.”

The significance of this routine that implies a version of the diddley bow and its gourd-hewed cousin of African origin, the banjo, is itself a bit inscrutable. Chalk that up to Faulkner’s overattention to detail without always providing connection. What rings true from this gothic peek into the underworld is the worn wooden mallet. That would have been the original tool required to make beaten biscuits. Dilsey would have rolled the dough onto a wooden slab and beaten the dough with the sizable mallet until the bubbles burst. Compared with the bluntness of the mallet, the wringers discarded from a washing machine seem like glisters from a gilded age of progress and advancement.

By now your mind is full of many things the biscuit brake has called forth or perhaps turned out: the fountain pen, the sweetness of the old woman who owned it first, her handwritten receipt, and the books, novels wrought from anguish and truth, hard to fathom and harder to digest. Beaten biscuits make a similarly offhand appearance in Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, and later appear almost incidentally in three novels by Walker Percy. In each, however, the biscuit maker is a grandmother. The wheels turning in your mind lurch to a stop. As with many other facets of truth, what you are about to endeavor is delicate and hard.

And so it is time, after seventy years it is time. You retrieve the receipt that calls for a quart of flour, the rounded teaspoons of baking powder, sugar, and salt, the four rounded tablespoons of lard, and a cup of cold water. You mix the dry ingredients and cut in the lard with a pair of forks, then stir in the water. Then you lay the dough on the marble slab and work it lightly before feeding it with your right hand into the kneader you turn with your left, over and over, until the dough is smooth and the bubbles burst in the choir loft of their own singular music. Cut the biscuits with the lip of a shot glass if one is handy, and prick each three times with a fork. Ten or eleven minutes in a hot, transfiguring oven. One pat of butter for the warm biscuit to receive and melt into itself like a sacrament. And soon, for a moment, the gloom is lifted, and the heart, though tried, for the brief span of ancient and sacred indulgence, is restored.

I suppose you might also need to be the sort of person who succumbs to the vicissitudes and curiosities and occasional wisdom of the proverbial wild hair, as well as one with the temerity to follow through. If that’s the case, then you are most likely one who believes that despite the brutal name, making a beaten biscuit is an honorable and decided art. It is a labor whose recompense cannot be measured and whose effort occasions no regret.