Like most Americans old enough to remember the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Michael Myers vividly recalls his whereabouts that morning. “I was at the intersection of Greenwich and Duane [in Manhattan] when the first plane hit, with my youngest son perched on my shoulders, taking him to school,” he says. His view south framed the abruptly altered landscape, and Myers, a Georgia native and successful fashion and beauty photographer, instinctively knew that the event marked a distinct split between before and after. The full shape of what came next for him, however, would take a decade to come into focus.

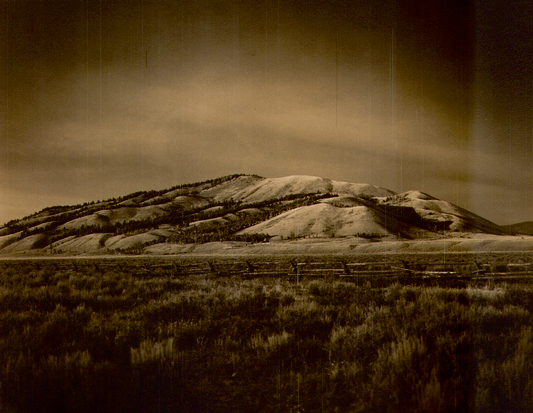

Myers and his family relocated to Colorado Springs, where his then-wife’s parents lived. It was intended to be temporary until the family could move back into their condominium building, three blocks from Ground Zero. But, after briefly moving back, they decided to make the transition permanent. Myers commuted to New York nearly every week for photography assignments. Flying back to Colorado in 2010 after a Vanity Fair shoot, he read an article about Steven Grasse, a marketing professional who’d created Hendrick’s Gin and Sailor Jerry Rum. Myers’s mind turned to whiskey. “I was looking for a change, and I thought, I’m from Georgia, they make it in the woods there. How hard can it be?”

Myers grew up on his family’s farm in Sandy Springs, just north of Atlanta. His family also raised Tennessee walking horses on a farm in Flat Creek, Tennessee, midway between the Jack Daniel’s Distillery and Cascade Hollow Distilling Co., where George Dickel is made. “I’ve been around whiskey a lot in my life,” he says. “I love Kentucky bourbon and I love Tennessee whiskey, but I set out to make a Colorado whiskey.” He envisioned something distinctly bold and flavorful, like what might have passed across the bar in a Western mining town.

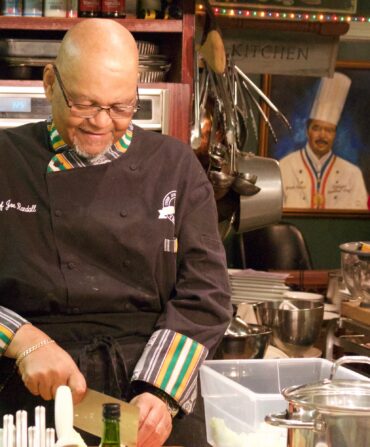

In addition to reading books and watching dozens of videos on distilling, Myers worked with the head brewer of Bristol Brewing Company to learn how to brew beer, an essential step in whiskey-making before distillation. When he realized it costs upward of $50,000 to purchase even the smallest still from Louisville-based Vendome Copper & Brass Works, he decided to make his own. Years earlier, Myers had exhibited a series of images at a gallery in Tribeca that represented important places in his life—Jackson, Wyoming; the Chrysler Building; the California desert—made using the photogravure method. Essentially, the negative of a photographic image is etched onto a copper plate, which is used to ink the image onto paper. He drew the design and dimensions he wanted for his pot still, made a paper mock-up, and took it and the copper plates from the exhibit to a local welder.

A series of delays dragged the project out over the summer of 2011, and the still wasn’t ready until early September. “I thought I might as well wait until September 11 to distill the first run, so that’s what I did,” Myers recalls. “It ended up being a nice way to remake the anniversary, but I probably would have started sooner without fate dragging it out.”

Myers chose to recast fate in a similar fashion in naming his distillery. During his first year as a student at the Savannah College of Art and Design, Myers’s dorm room was number 291. He later learned that, in 1907, Alfred Stieglitz opened the first gallery dedicated solely to photography at 291 Fifth Avenue in New York. “I said, ‘Okay, I’m meant to be a photographer,’” Myers recalls. “And when it came to making whiskey and building a still out of photogravure plates, it was 291 Colorado Whiskey.”

While the symbolism of crafting a new life from pieces of his old one isn’t lost on Myers, he sees the genesis of that first still more as a matter of practicality. “It was what I had available at hand,” he says. He adopted a similar attitude over his first three years of operation, working solo to distill, age, blend, and bottle thirty-gallon batches of bourbon and rye inside a three-hundred-square-foot facility. “I felt like I was back on the farm,” he says of hauling sacks of grain and buckets of liquid. He likens cooking corn mash to making a giant batch of grits.

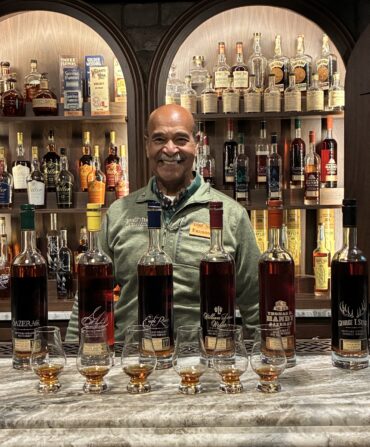

Over the past twelve years, Distillery 291 has grown into a much larger facility, but its recipes and hands-on process remain essentially unchanged. Although its output is still relatively small—“The big distilleries in Kentucky probably spill more whiskey than we make in a year,” says marketing and sales director Emily Rhoades—Distillery 291 has established an outsized reputation and won international recognition, including World’s Best Rye from the World Whiskies Awards and the Icons of Whisky 2022 American Craft Producer of the Year.

Since the beginning, the distillery has used malted rye varieties more common in brewing beer than in making whiskey—although lately that trend is catching on in distillation. Its whiskies are triple-distilled, with conservative “cuts” to capture only the heart of each distillation run. Its bourbons and ryes are aged in small-format barrels and finished with toasted Aspen staves, complementing the whiskey’s naturally spicy, bold flavors with notes of baking spice, maple syrup, and a hint of smoke.

Myers’s original pot still remains in use, only now as a “thumper” to further refine the output of the primary stills. The view out the back of the distillery frames Pikes Peak and the Front Range. And in the right light, you can still make out the faint images in the copper.

Tom Wilmes is a journalist based in central Kentucky, specializing in bourbon and other spirits. A contributor for Garden & Gun, he has also written for Whisky Advocate, The Local Palate, Southbound, and various other publications. Follow @kentuckydrinks on Instagram.