The strictures of bourbon-making are narrowly defined—it must be distilled in the United States using at least 51 percent corn and aged in a new, charred oak container, among other conditions. But as tastes continue to evolve, there’s more room for experimentation to enhance flavor and complexity. An increasingly popular technique is “finishing” a mature bourbon in a second vessel previously used to age another spirit or wine, such as rum, port, or sherry. The resulting spirit can no longer be solely designated as “bourbon” due to this secondary aging, and its label must reflect that extra step. Common terms one might see include “bourbon finished in,” “cask finished,” or “double-wood finished.”

“It’s fascinating to watch these master distillers decide what flavors they want to celebrate in a bourbon, and then take it even further,” says Peggy Noe Stevens, a consultant with more than thirty years’ experience in the whiskey business. Based in Louisville, she’s also the world’s first female certified master bourbon taster, and pens dozens of reviews each year, including of finished bourbons. “It’s like a chef creating a great recipe—you really have to know the deep-down flavor profile of your original bourbon before you decide ‘what do we want to enhance?’” she says of creating complementary flavors without overpowering. “For example, I might taste a cherry note in a bourbon, and if I use Oloroso [sherry] barrels, then I’ve just heightened that to an almost blackberry, sherry-like flavor.” A short stint in a secondary barrel is often all it takes.

Distillers of Scotch whisky have long aged their products in used barrels—often bourbon barrels exported from the U.S.—and in recent decades have experimented with cask finishes. In 1999, the late Jim Beam master distiller Booker Noe, to whom Stevens is related, became the first major American distiller to release a cask-finished bourbon with Distiller’s Masterpiece. Selected from stocks aged for eighteen years, the whiskey was finished with a dip in barrels previously used to age cognac and packaged in an ornate decanter. It’s likely that the sky-high price (for the time) of $250, rather than the whiskey itself, turned off regular drinkers, and Distiller’s Masterpiece languished on shelves collecting dust.

As was often the case, Noe was ahead of his time. Jim Beam later released Legent, created in collaboration with Shinji Fukuyo, chief blender of Suntory Whisky (a sister company also owned by Suntory Global Spirits), and seventh-generation master distiller Fred Noe from a blend of Kentucky bourbons aged in both red wine and sherry casks. In 2023, it released a version that also includes a portion of bourbon finished in casks previously used to age Yamazaki Single Malt Japanese Whisky.

“I think you’re going to continue to see more finishes and more creativity in the industry,” Stevens says. Here are three examples that showcase a range of flavors derived from the approach.

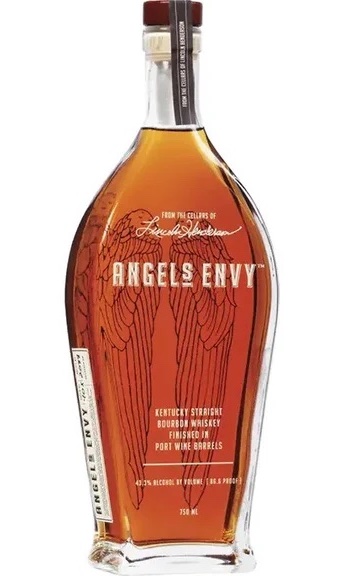

Angel’s Envy is a widely available small-batch whiskey finished in ruby port wine casks. “If you’ve ever had a cheese that’s soaked in port, it just goes together so well,” Stevens says. “Port also works fabulously as a bourbon finish.” Angel’s Envy also offers a rye finished in rum barrels, and it released a limited-edition whiskey finished in Oloroso sherry casks as part of its Cellar Collection.

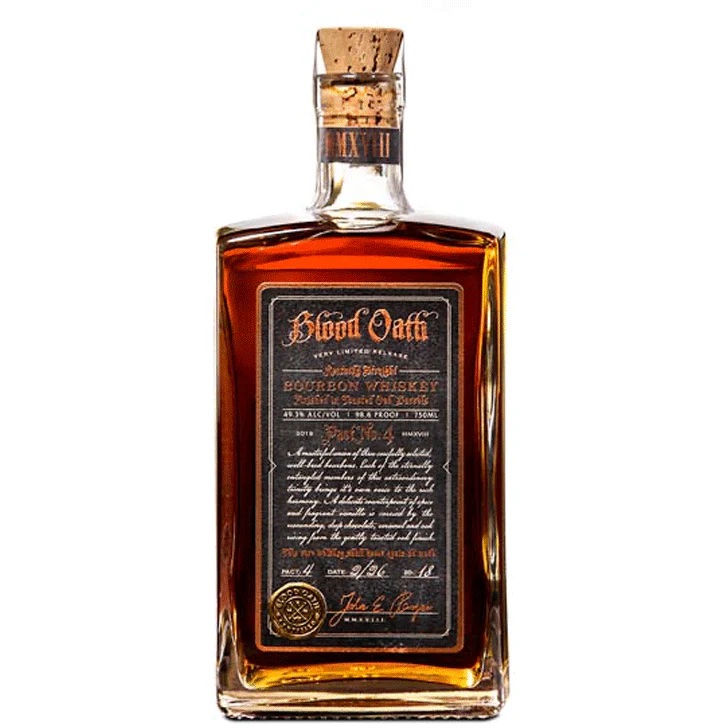

Given the culinary parallels in blending and finishing whiskey, it isn’t surprising that John Rempe, the master distiller behind Blood Oath whiskey from Lux Row Distillers, is also a food scientist. While each “pact” of Blood Oath is unique, the limited-edition bottlings are often blended from select barrels and cask finished. Pact No. 3, for example, is a blend of three bourbons finished in Cabernet Sauvignon barrels. “You might think, red wine joined with bourbon? That doesn’t sound right,” Stevens says. “But what they were trying to do is bring out coffee notes, dark fruit, and stone fruit, and they were very successful in doing so.” The current release, Pact No. 11, is a blend of three bourbons finished in Añejo tequila barrels.

Jefferson’s Reserve Pritchard Hill Cabernet Finish, released occasionally, is another successful example of whiskey finished in Cabernet Sauvignon barrels—in this case from an award-winning Napa Valley winery. Mature Jefferson’s Reserve bourbon is aged an additional year in French Oak casks that previously held Pritchard Hill Cabernet Sauvignon, lending sweet notes of “dark berry, espresso, and chocolate.”