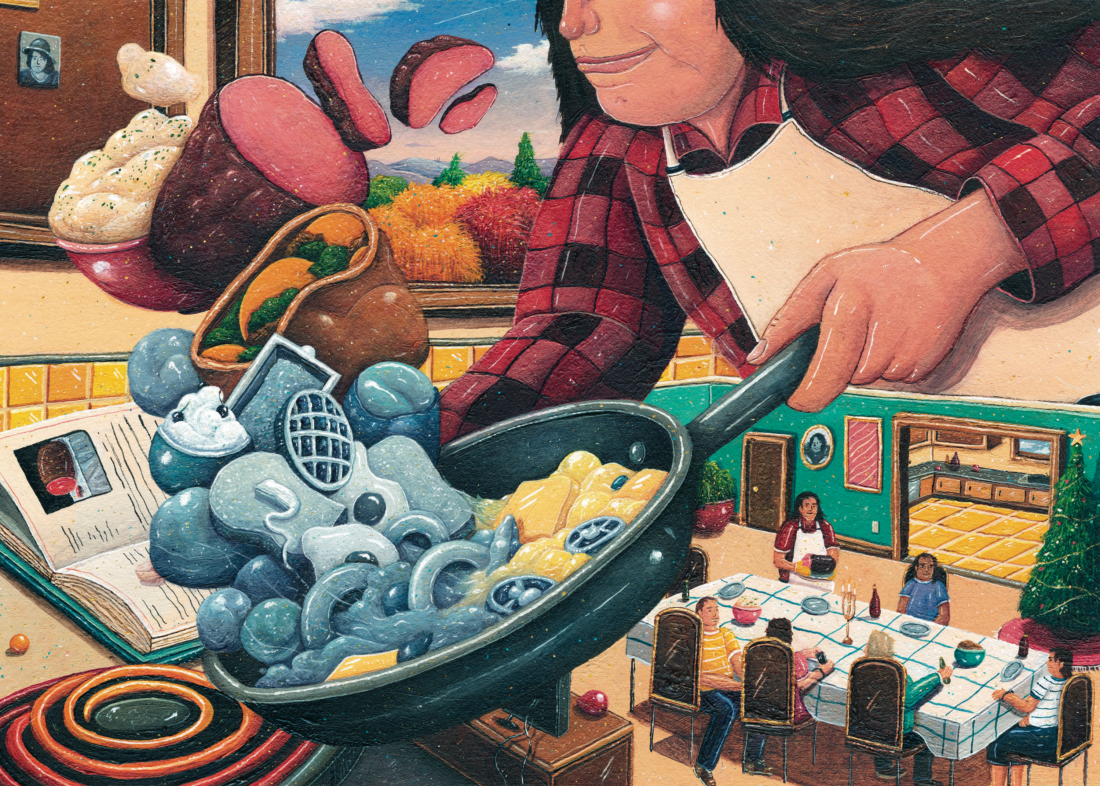

Portland, Tennessee, was a town so small that the arrival of Mamma’s grandchildren—my mother and her four siblings among them—got announced in the local paper. They came during summers and holidays, filling the large white clapboard house. I imagine my great-grandmother preparing for their visit, bustling over the yellow-tiled floor of her kitchen, between its seven doors—including to the screened-in porch where she slept nearly year-round; to the sewing room with scraps of cloth, needled pincushions, and wintertime bed; to the wallpapered dining room; to the pantry; and to the second screened-in porch she used as a kind of root cellar.

In old photographs, Mamma—who died before I was born—appears invariably stern, her pursed lips forming an exact horizontal line. But by all accounts, her outward restraint belied an inner exuberance—a love of daily life in its small domestic glories.

Her kitchen was the hub of that daily life. When her grandchildren came to Portland, she fried green apples dusted with cinnamon and sugar, and corn and bacon and eggs; she made toast with brown sugar and butter that melted into a gooey delight. She baked constantly: Japanese fruit pies with white raisins, pecans, and coconut. Strawberry pies in late spring, apple pies in the fall. On holidays, she made an abundant amount of her most famous dish—known simply, many generations later, as Mamma’s rolls.

Mamma’s rolls take Southern comfort food to the next level. They offer a smorgasbord of subtle flavors and textures in one unassuming doughy disk. Their sweetness pairs with a yeasty, sour quality; their smooth tops are dusty with flour. They are impossibly soft and dense at once, and best served with an oozing pat of butter. When I was growing up, they were a staple of every holiday.

* * *

With hardworking middle-class parents, my siblings and I were among the “latchkey kids” of the eighties and nineties. Meals were often quick and easy: macaroni and cheese, boiled hot dogs, Hot Pockets.

The holidays, however, were special. Despite three children and twelve-hour hospital shifts, Mom always found the time and energy to make our favorite family recipes—most passed down from her own mom and from Mamma before her. At Thanksgiving, she turned out a spinach casserole with four kinds of cheese, ambrosia salad, mashed potatoes, and—of course—Mamma’s rolls. One month later, at Christmas, she made it all again.

I did not inherit this commitment to cooking, and stick with meals I can throw together in minutes: scrambled eggs, or precooked chicken sausages over a bowl of prewashed mixed greens. Even so, I get inconsistent results. The sausages often wind up burned, the eggs dry and clumpy. When I attempt to soft-boil eggs, they come out too runny, or else fully hard-boiled.

All of the care that made Mamma’s food so memorable and that I find so daunting, my younger brother, JD, inherited instead.

If Mamma is a symbol of Southern quaintness, JD is the opposite. In each earlobe, he sports gauges the size of a quarter. His dark, often tangled hair falls far past his shoulders, and he wears black jeans and a flannel shirt even during the humid Virginia summers.

In the kitchen, JD is meticulous if not downright obsessive. Unlike his sister, he gets consistently soft-boiled eggs—and establishing consistency seems, in fact, to drive his cooking. I once watched him pluck exactly twenty-four basil leaves for a roasted salmon dish. He measures ingredients and even coffee grounds to the gram. If he sees me eyeballing my own grounds, I can sense him holding back commentary, and—even if no words are exchanged—the air in the room turns slightly taut.

* * *

My brother is eight years younger than me, and when we were both still children, I loved looking after him. I remember holding him as a baby while he napped on my shoulder. I liked taking over bedtime routines at night, reading him stories until he fell asleep.

Then, when he was in elementary school, a family friend with whom he’d shared a close bond died unexpectedly. In his grief and confusion, JD’s behavior spiraled. He acted distant one day, volatile the next. He had angry, sometimes violent emotional outbursts. At some point in my parents’ long quest for answers, he was diagnosed, at only eight years old, with severe depression and anxiety.

Occasionally, I would try to come up with an activity that would force us to bond again. One summer, I took him bowling—not considering that new activities caused his anxiety to spike. After we got our shoes on and the lane set up, he shut down, refusing to bowl. I couldn’t understand. I felt hurt—then angry. I barely spoke to him as we crossed the parking lot to my beat-up car.

Looking back now, I see us both more clearly: two vulnerable kids stalking across the glittering asphalt. One scared of the world; one scared to see how much each of us, in our own ways, was suffering.

* * *

JD was ten when I left home for college in Richmond, followed by moves to Pittsburgh for graduate school; to Austin, Texas, to start my writing career; and finally, back east to Brooklyn, where I live now. My brother stayed in Virginia with my parents, and when I would go home for the holidays, the same sadness, anger, and helplessness that I felt when we were younger came alive again, deep in my stomach, like a bundle of exposed live wires. In those moments, it could feel like so little had changed.

JD’s interest in cooking, however, kept expanding—and grew to include holiday meals. At first, Mom continued making our Southern staples, and my brother took over the meat. One Christmas he prepared both a prime rib roast and roasted chateaubriand—a juicy center-cut tenderloin with a red wine sauce. He juggled the roasts in a small oven, somehow timing them both to come out at the perfect temperature, at the perfect moment.

In December 2020, I flew back to Virginia for Christmas, eager, after our first pandemic year, to enjoy our usual holiday comfort foods. JD had other plans. For days, he worked to prepare an all-new menu, talking excitedly about vegetables Wellington—a play on beef Wellington—and the brisket he’d smoke on the charcoal grill. I heard no mention of my beloved traditional dishes, and secretly, I was disgruntled. I wanted to be grateful that he was doing all of the work while I sat fireside with a glass of wine—but these were not the recipes passed through generations, the ones that have always created for me what cooking now creates for my brother: something consistent and comforting in an unsteady, painful world.

When dinner was ready, my family and I took our plates of food and gathered on the couch and easy chairs in our living room, surrounded by the soft glow of the synthetic Christmas tree. My brother stood eagerly in the kitchen, as he often does while we try whatever new dish he’s made. Skeptical, I dug into my slice of vegetables Wellington.

I remember it vividly: the flaky phyllo, the burst of flavors and textures. Rather than offering our usual exclamations of praise, we ate quietly, savoring the crunch of ground cashews; the sweetness of roasted carrots; the way the herbs mingled with the smoky quality of the mushrooms—and I sensed something deeper than taste itself. In the kitchen doorway, JD beamed.

Our familiar family recipes remain a connection to our past—to Mamma’s goodness and groundedness, to Mom’s Herculean effort to make our childhood holidays comforting and special. And though at our most recent holiday meals, I requested the return of Mamma’s rolls (and helped prepare them), my brother’s new dishes, and the care he pours into them, have ushered in something surprising: a connection to the deliciousness of the present—and to a long-haired, meticulous individual, finding his own steadiness in the kitchen, introducing us to flavors we hadn’t known we wanted.