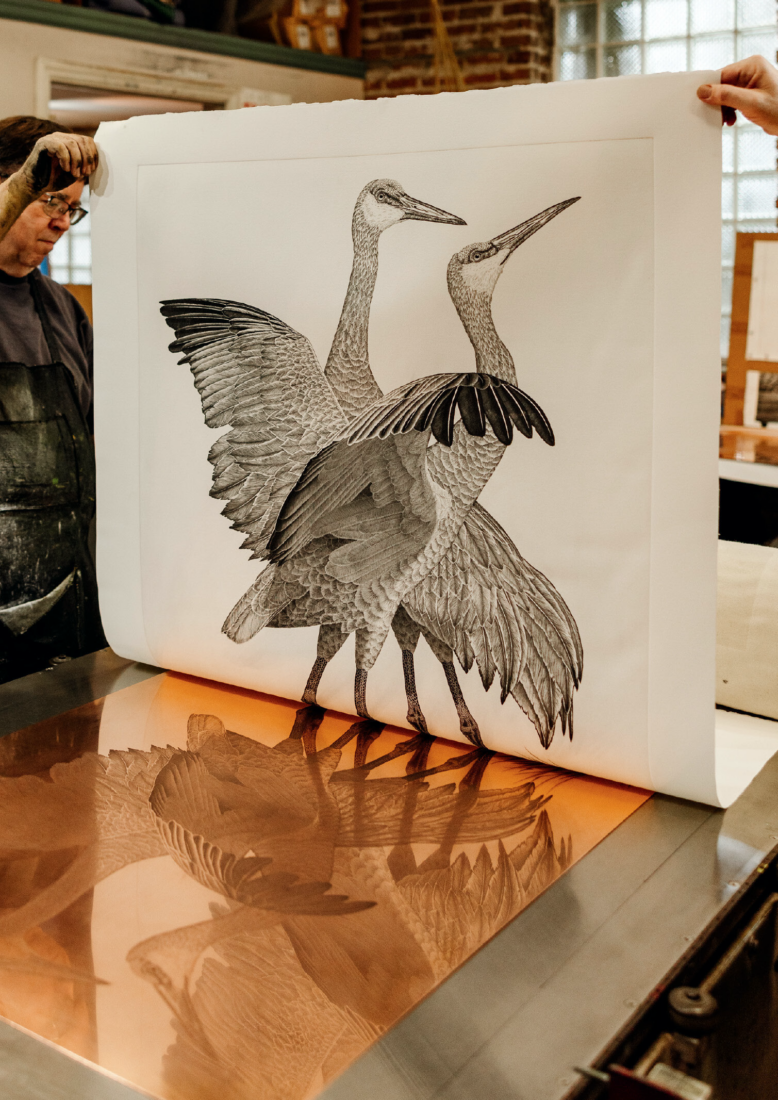

Surrounded by ink-soaked sponges spilling from a tower of tin pails, scraps of paper smudged with color tests, and scribbled notes tacked to the walls, John Costin runs his thumb over a thin sheet of copper. Measuring thirty-one and a half by forty-six inches, the sheet serves as the key plate for Verdant Landscape, an etching of sandhill cranes he’s worked on for more than six months here in his Tampa studio, formerly an early-1900s dry goods store.

“This is a plate that I generally do first, and it has all the detail on it,” Costin explains. “I’ve etched these plates I don’t know how many times, and I still haven’t finished. I dream about this bird.”

Costin, who is sixty-six, became “fascinated with birds” as a teenager when he moved with his family from Detroit to Lake Wales, Florida, in 1969. Today he’s an avid birder and carries his camera to snap photos of different species that he then catalogues to inspire future etchings. The pages of an oversize book he compiled of his pieces titled Large Florida Birds reveal his passion—in the striking details of his majestic anhinga, stoic brown pelican, and vivid roseate spoonbill.

“Even when I was a child, I was interested in art and making drawings and paintings,” Costin says. “But I never thought I would be an artist as a profession.” Instead, Costin joined his father in electrical work and carved out a successful career. Art held its allure, however, and he enrolled in classes at the University of South Florida in 1979. There, he learned about printmaking, a medium that traces its roots to about the second century in China, and the basics of etchings, first produced in Germany around 1500.

“It was such a good fit for me because of the way my mind works,” he says. “On my own, I just started working on it and designed my own press”—an apparatus that now stands in the middle of his studio—“and wow…I took off with it like a sort of mad scientist in his laboratory, trying this and trying that and problem-solving.”

Turning back to the sandhill cranes, Costin explains his process: After choosing a subject, he sketches the bird—first in pencil, then in watercolor—and from that creates a small, detailed drawing. Once satisfied with the depiction, he turns it into a life-size version, and then redraws the detailed rendering onto a copper key plate using a pencil. Next, he etches the rendering into the surface using ferric chloride acid.

“I like the idea that when viewers see these images, they get a sense of what this bird is like in the real world, because of its scale,” he says. “You can see the detail on the legs, for instance, the scaling patterns”—legs that alone accounted for forty hours of work.

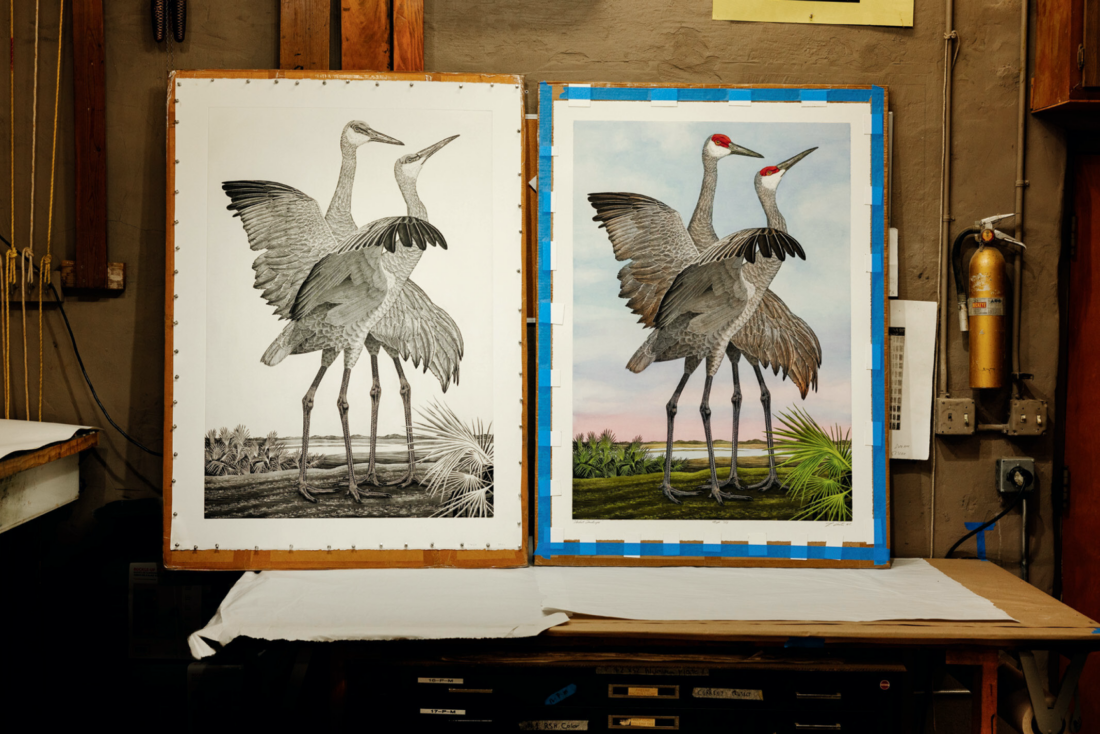

Once Costin finishes the detailing on the key plate, he transfers the image to another clean plate and begins applying color by etching areas such as the sky or trees with their respective hues. He applies these pigments a la poupee, which means adding more than one color to the same plate for printing. Because copper oxidizes and muddies colors, he achieves his vibrant hues by facing his plates with a sheet of paper-thin steel.

Problem-solving like that also comes into play during the color printing process: When paper goes through the press, it stretches. Costin takes that stretching into account by working with multiple plates of different sizes to ensure everything aligns on its way to a final image. Florida’s humidity can also impact the prints’ registrations.

“Not many artists did colored etchings; it’s extremely rare,” Costin says of his predecessors. “In most cases, they’re printed in black and white, then they’re hand painted because registration is so difficult.” He elaborates, leafing through a pile of proofs to show examples from his own trial and error: “Have you ever seen a newspaper where it looks like you need 3D glasses? That’s where the registration is off. There’s a layer of engineering that goes into these as much as the artwork, so I’m working with both sides of the brain.”

In that stage, “I’m actually creating a physical texture, which is more like sculpture than a drawing or painting,” he adds. “What that texture does is it holds ink to the surface, and then when it transfers to paper, that’s where I get my image.”

Once Costin is happy with his final proof, he determines the number of prints to make in the series and begins his final step: hand painting the finer details with watercolors, which presents its own challenges. “The ink is oil based, and the paints are water based,” he says, so he has to manipulate the paints so the two work together. “If I don’t, they sit on top of each other, and visually, it doesn’t look right.”

That attention to detail has won Costin admirers across the world, and closer to home, too. Brad Massey, the curator of public history at the Tampa Bay History Center, built a new exhibition there inspired by Costin’s work. Etched Feathers: A History of the Printed Bird runs through October 15. “After talking to John, we decided that his process and his ultimate product are just so interesting and mesmerizing that we should really do a show about them,” Massey says.

In addition to Costin’s etchings, the exhibition follows the evolution of the printing process through the centuries and showcases bird prints dating back hundreds of years, pulled from Costin’s personal collection, along with two rare books by the English naturalist Mark Catesby on loan from the University of South Florida. Costin has acquired his set of antique prints over the past thirty years, enthralled by “the history, the time period, the subject matter, how different artists of different eras approached making imagery,” he says. Earlier ones were more primitive, but “as history goes on and people learn more about the process, you can see how the images become more refined, and how they use space and perspective,” he continues, noting that John James Audubon’s and Catesby’s renderings became scientific documentations of bird species.

As for his own evolution, “I experiment all the time,” he says. “This process is made for experimentation. You’re only limited by your imagination.”