It’s not entirely uncommon for college football stadiums to double as burial grounds. At the University of Georgia’s Sanford Stadium in Athens, for example, Dawgs fans have interred all nine of their beloved Ugas near the southwest corner of the end zone. Over at Mississippi State in Starkville, the SEC’s other bulldogs spread the ashes of some of their former mascots on the field—the first Bully was even buried beneath the sideline bench on the fifty-yard line. Alabama’s Bryant-Denny Stadium in Tuscaloosa sits about one hundred feet from an actual cemetery dating to the 1830s. Perhaps the most unusual, though, is Florida State University’s Sod Cemetery: a colorful and well-kept resting place for chunks of grass and dirt ripped from opponents’ fields after a victory.

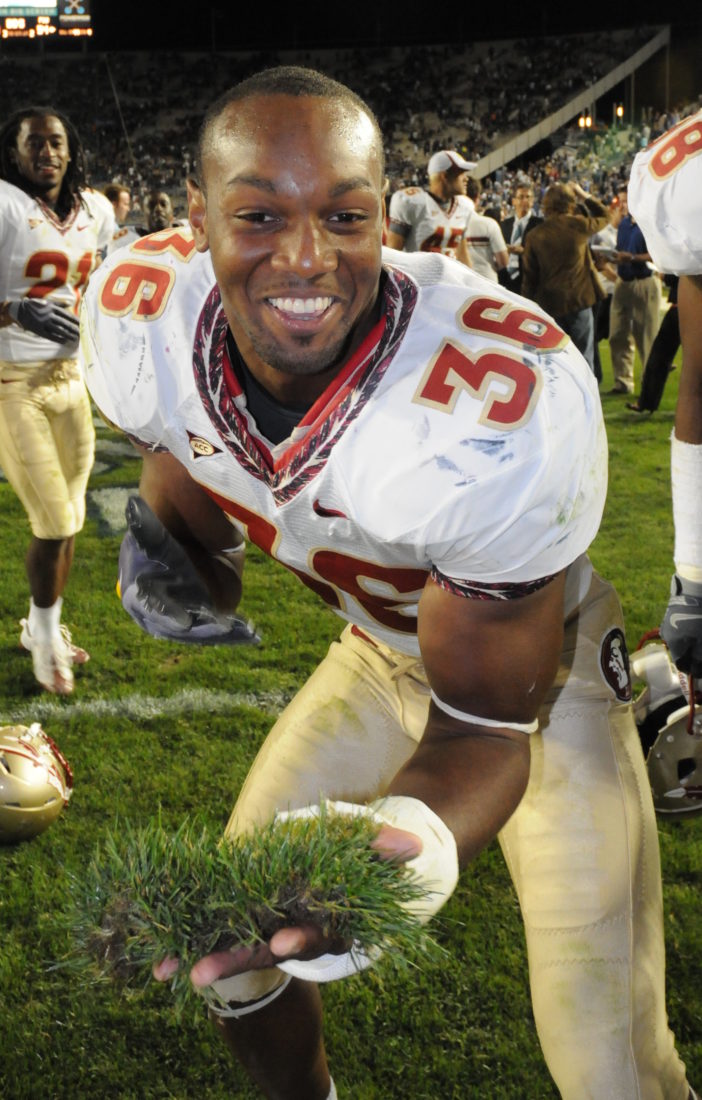

Photo: Courtesy of Florida State University

FSU’s Sod Cemetery.

No one tells the story of how this tradition came to be better than Doug Mannheimer, a lawyer-turned-part-time-cemetery-keeper, who has overseen FSU’s hallowed institution since the job was passed on to him in 1988. “It’s a grave responsibility,” he laughs, “but it’s a lot of fun.” It started like this:

In 1962, FSU’s football team was only fifteen years old; prior to that, the school had been a women’s college. Perpetual underdogs, the team needed some encouragement. Enter Dean Coyle Moore, “a wonderful and unusual guy who was dean of the school of social work and loved college athletics,” Mannheimer says. “We were about to play UGA. They were ranked fifth and FSU was thoroughly unranked.”

Before the team left for Athens, Moore gave an encouraging speech, ending it with a charge: win, and bring back a little sod from between the hedges. The Seminoles did just that, upsetting Georgia 18-0. Two players returned home to Tallahassee with dirt in a paper Coca-Cola cup, which Moore kept on his living room mantel until his wife made him find another, more appropriate spot for it. He, along with Bill Peterson, the team’s head coach at the time, decided to plant the sod outside the stadium beneath a marker that noted the year, the opponent, and the score. Today 105 graves lie in a gated greenspace across the street from the stadium, adjacent to the practice field.

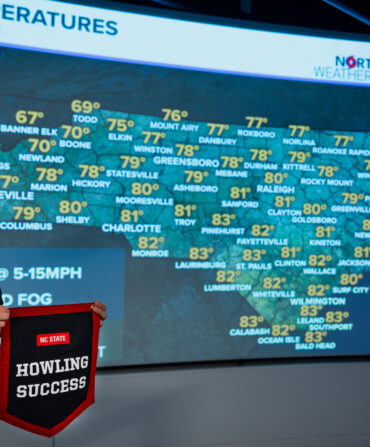

Photo: Courtesy of Florida State University

Sod from Clemson’s “Death Valley” in an open casket after FSU beat the Tigers on October 19, 2013.

“Sod games are away games when FSU is the underdog or slightly favored, a big game on the road, any game we play Florida in Gainesville, and all ACC or National Championships,” Mannheimer says, although ultimately, the decision is up to the head coach. If he deems the upcoming match-up a sod game, he’ll alert Mannheimer and choose a sod captain on Thursday. If Saturday is a success, Mannheimer will usually receive the sod in a plastic bag on Sunday afternoon.

It’s his job, then to order a marker from a West Virginia foundry that makes the engraved tombstones, flat on top and extending three feet into the ground. Until it’s ready to bury, the dirt is kept in an undisclosed location. On gamedays, that sod will sometimes be placed in an open casket with sashes and flowers, so fans can pay their respects.

Of course, this tradition comes with a little good-hearted taunting. “When an opponent comes to Tallahassee, we put flowers of their color around each of their graves,” Mannheimer says. “We like to honor the departed.”

Read about Southern college football traditions:

>> Georgia’s hedges: How they endure and thrive

>> Florida State’s Sod Cemetery: “A grave responsibility”

>> Auburn’s Toomer’s Corner: Touchdowns, trees, two-ply

>> LSU’s Mike the Tiger: Always on the prowl

>> Tennessee’s Vol Navy: Sailgating on the river