Quilters’ eyes and hands work in tandem, translating rural Southern surroundings into the stitchwork at their fingertips: Flocks of migratory warblers and blackbirds evolve into pointed triangles, all veering toward the same direction; rural rooftops melt into stacked slats of cherry red, cornflower blue, and strips of plaids and ditsy florals. “Any abstract artist is taking things from the real world and reducing and formulating it into arrangements of shapes and color,” says Katherine Jentleson, the High Museum of Art’s senior curator of American art and Merrie and Dan Boone curator of folk and self-taught art.

Historically, quiltmakers, many of them women, were left out of the canon of fine art, separated by a distinction between domestic “craft” and modern art. Jentleson’s show leaves viewers to explore the beauty and brilliance of Southern quilters, many of whom were not academically trained but instead learned techniques passed through generations of family and community circles. For guests and museums alike, she poses the question: “How can quilts made by Black women change the way we tell the history of abstract art?”

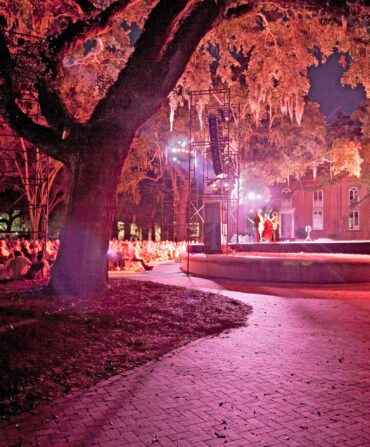

The High’s newest show, Patterns in Abstraction, which runs until January 5, 2025, presents seventeen of the High’s quilts, including the work of Alabama’s renowned Gee’s Bend quilters. In 2017, when Jentleson joined the team at the museum, she immediately knew she wanted to add more fiber works to the collection. “They are incredible objects, but they’re sensitive,” she says, referencing the delicacy required to handle them in a gallery setting. Lights can cause colors to fade; fabric grows brittle and dyes weaken naturally over time; the gravity of hanging them on a wall can damage the shape. Even the most impressive pieces from the museum’s permanent collection—examples from the eighties like Faith Ringgold’s Church Picnic Story Quilt and Jessie Telfair’s Freedom Quilt—must periodically rotate out of view for their protection.

But in the past six years, the museum has quintupled its holdings, including thirteen pieces from Gee’s Bend, twenty-six from a West Coast collection of unidentified makers that adopt improvisational styles similar to those in the South, and several purchases from contemporary artists including Marquetta Johnson, Bisa Butler, and Dawn Williams Boyd. “These big acquisitions meant from that point forward, we could hold a place for quilts in galleries,” Jentleson says. “When visitors come to the museum, they know they will see great examples of artwork from Black women.”

The exhibition takes a closer look at the popular centuries-old Birds in the Air and Housetop patterns, using these variations as a foundation to study how artists reconfigured their lived experience into evocative artworks. “Quilters are thinking about the real world—architecture and migrating birds—and making patterns to correspond to what they’re seeing,” Jentleson says. “Artists arrange birds in directional contrasting triangles that create a sense of movement, mimicking their migratory patterns.”

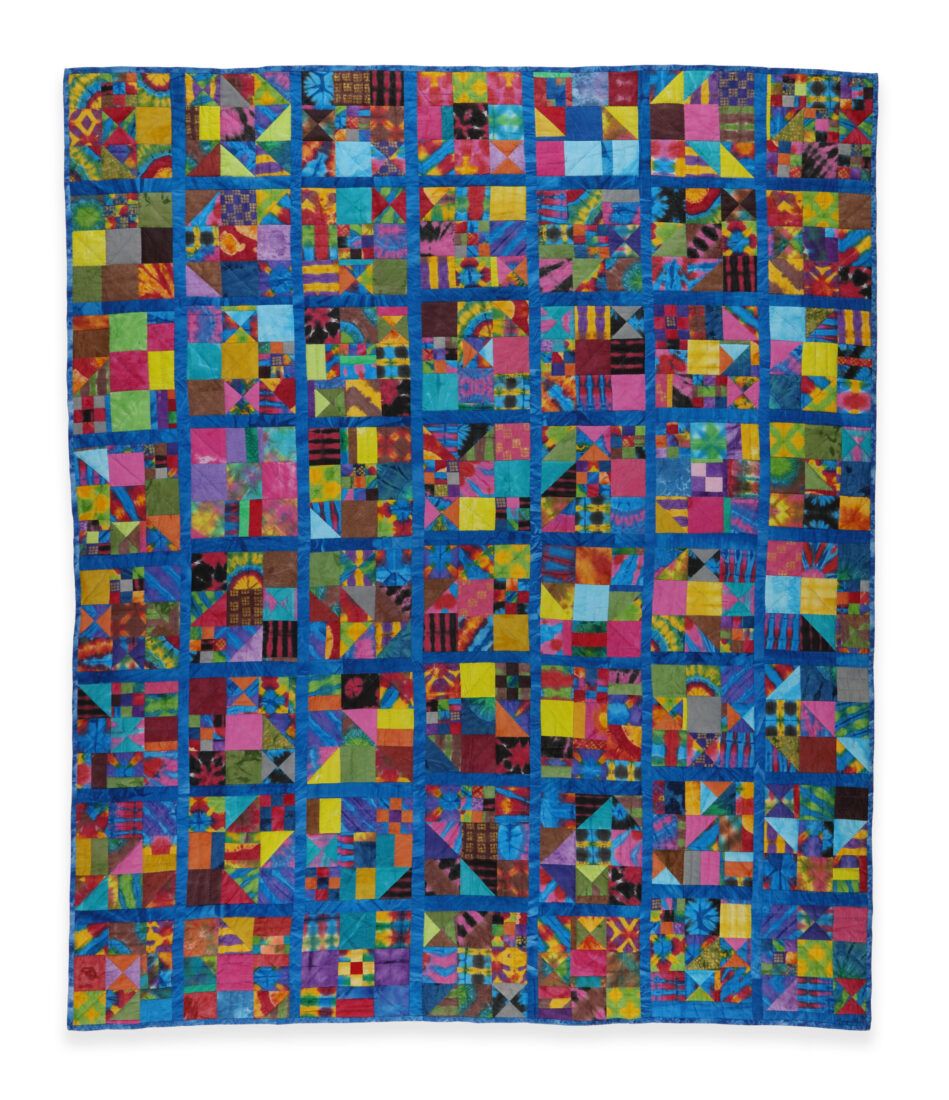

The pieces from the legendary quilters of Gee’s Bend, including Lucy T. Pettway, Louisiana and Mary Lee Bendolph, and Annie Mae Young, shine individually, but they also allow viewers to connect threads between works created in the same community. Informed by the patterns she produced at the Freedom Quilting Bee textile factory and her aunt’s pattern book, Pettway’s methodical and geometric shapes allowed her to investigate wide color palettes and bold compositions. Her 1981 Birds in the Air quilt plays with the scale of neat black, gold, cream, red, and purple triangles, designing a blanket of vibrating light, shadow, and rhythmic motion with high-contrast forms stacked beside one another.

While Pettway is known for her perfectionism and precise technique, other quilts in the show adopt a lyrical, freeform arrangement, offering a diverse look into the ways these artists can study the interactions of form, color, and layout. In a red, cream, and blue quilt from an unknown artist, a layered Housetop pattern brings together squares, strips, and slices of striped and star-dotted fabric, concentrating and simplifying American flag imagery into found material. Like in Pettway’s Birds in the Air quilt, the unknown artist investigates rhythm and motion through the material’s shape and placement—but where Pettway’s symmetrical triangles point in the same direction, this red and blue quilt displays tilted, varied sections of cotton to create a rippling sense of movement, a collection of flags caught in the wind.

Jentleson is also interested in studying the history of each thread. In the High’s interviews with known makers and family members, they describe the past of each item. Many of the pieces were utilitarian objects, passed through generations of families to keep grandmothers warm, to cocoon babies, and to act as a playground for crawling children. In an example from China Pettway, she repurposes brown, red, and black corduroy clothing her mother had once made for her and her siblings. Jentleson says that in a discussion with China, she remembered how her brother hated his pepper-colored fabric, but she adored her smart-looking skirt; she saved the garments for years until she deconstructed them for a blanket. “Her kids played on different sides of the quilt,” Jentleson recalls, noting the places where the quilt has worn over time. When Will Arnett, a Southern collector and founder of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, first saw the quilt, China was surprised he preferred the well-loved brown side of the quilt. “These quilts have these amazing stories with them. Their life precedes the museum.”

Guests at the High can learn more about artists, specific pieces, and themes throughout the Patterns in Abstraction with LINK, a collection of interviews and videos.