Q. What makes a true “heirloom” tomato? A neighbor is trumpeting the world-class pedigree of her vines.

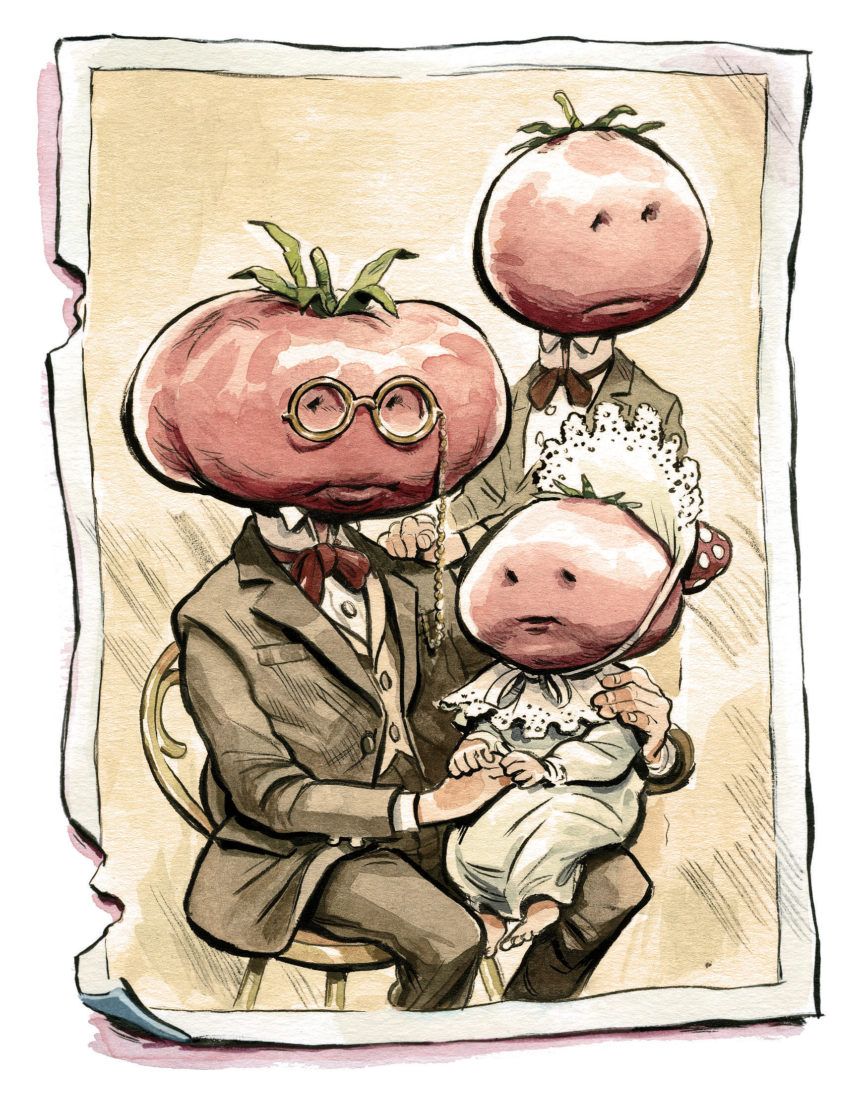

This is also wedding season, so if fending off your neighbor isn’t challenge enough, raise the topic among the gardeners you know at the next reception. And be grateful for every fight that will rain down upon you. It speaks to the South’s agrarian health that we are so willing to take to the battlements over gardens, and specifically over the cultivation of the nightshade family. Southerners care about their ’maters. The heirloom debates are a hard-fought front in the wider tomato wars, and a jolly one. The reason is (that tearing Velcro sound you hear is me tightening my body armor): There is no such thing as an heirloom tomato. Put more diplomatically, every tomato variety is, by definition, with the passage of time, technically an “heirloom.” Legions of aficionados—seed savers, commercial and private farmers, and plain-ass old tomatoheads—are out there mixing, matching, and madly cross-pollinating new ones for us 24/7/365. Of course, we all know what we mean when we use the word heirloom, namely, an old variety passed down. Some of these varieties bear fantastic fruit, if they fit your climatic zone. Three heirlooms born and bred in the South are: the Cherokee Purple, which came from a family in Sevierville, Tennessee, who received the seeds from the Cherokee; the hardy Arkansas Traveler; and our favorite, painstakingly developed during the 1930s in Logan, West Virginia, by

ace truck-radiator repairman Marshall Cletis (Charlie) Byles. It’s called Radiator Charlie’s Mortgage Lifter, because the plants he sold paid off his house. If you really want to cut your neighbor’s egregious lectures short next summer, tell her you’ve put in a bed of Radiator Charlies.

Q. Is Florida officially Southern?

Of course it is. You’re being confused by that whole hubba-hubba P. T. Barnum stuffed-gator-and-swim-float salesman thing they do down there, and the scrim of condo-village blandness, not to mention the blacked-out SUVs now swarming around Mar-a-Lago. Ignore all that. When I was growing up in Alabama, we visited our cousins in Florida with joy and trepidation, because, well, anything could happen: gators wandering Fort Lauderdale backyards casually devouring dogs, barracuda jauntily thrashing unbidden into your boat, twenty-square-mile blooms of jellyfish, bales of marijuana washing in. Licentious all-night parties with scantily clad women on yachts back in the canals. Big fish, no rules. For a high- school prank, a Florida friend of mine would take his skiff out at night, catch a sand shark out on the flats by hand, with no hook, then hurry it back to dump it in a swimming pool he and his friends had targeted. When folks came down for their morning dip: ¡Buenos días! In my childhood view, anything that happened in Florida, even the giant waterspouts when we were out fishing, took on a biblical, doomsday edge. Everything happened because it was Florida, but doomsday never really arrived. Doomsday was somehow put under arrest at the state line. That’s what makes Florida the South.

Q. It’s hot. How far into fancy dress can we take linen?

Not very far. Linen has spent a few centuries meandering from underwear to outerwear—meaning, generally, from the eighteenth-century chemise to Atticus Finch’s godlike rumpled white linen suits in the un-air-conditioned courtroom of 1930s Maycomb, Alabama. Flax fibers are famously conductive, so the garments are cool—hence the preference to put linen next to the skin, as bedclothes, underwear, and shirts. My grandfather had linen collars for his cotton shirts, not least because they took the starch better. Our brutal summers have broadened the fabric’s range, but its curlicued transition to outerwear has left the fabric a subtle scale of dress. In this season, especially on the torrid coastal plains, linen can be worn on most occasions, barring funerals and black tie. Whether it should be worn is subject to a tacit, contradictory body of law. Linen looks best in the daytime, thus the fresh zing a crisp linen dress brings to a garden party. Women can wear linen to evening events, but as the sun sets, the fabric has a way of turning men into fops. Let’s engage in some fun reverse sexism and remind everybody that, in the South, men are not supposed to be comfortable, ever, really. For evening “business” functions indoors, the boys will want to remember the tropical wools in their closets. Not every man can pull off a linen suit like Atticus.