Much to our parents’ chagrin, my wife and I adopted Layla out of wedlock.

We were both raised in the Bible Belt. A dog wasn’t as bad as moving in together prior to tying the knot, but it was close. Maybe I’m not giving our parents enough credit. Maybe they just didn’t think we were ready for such a commitment.

I was about to start my first year as a high school teacher and coach, while Mallory was working night shifts at a nearby hospital. We were busy, but damn, we wanted a dog. Not just any dog. A blue-eyed dog. The bluer the better.

Fast-forward a few weeks, and we were sitting outside a Harps supermarket in Marshall, Arkansas, watching a woman slide out of a Dodge with not one but three blue-eyed dogs dangling from her forearms like possums from a branch.

The woman didn’t have papers, but she said the momma was “a Aussie.” We didn’t care about papers. We had a choice to make. There were two boys and a girl. The males kept tumbling over the wheel stops in the grocery store’s lot, wobbling off toward Highway 65. The female, on the other hand, went straight for Mallory and never looked back.

We were married a few months later, and Layla was in the wedding. She went with me to football practices and stayed in the bullpen during baseball season. Layla was one year old when we took her canoeing on the Mulberry River. A mile or so in, we stopped above a rapid for lunch. Before we’d unwrapped our sandwiches, we heard a sharp yip, followed by splashing.

Our dog was being sucked downstream.

Or so we thought.

It wasn’t until Layla had exited the current, run up the bank, and jumped back into the river that we understood what was going on. She was riding the rapid down, and she kept riding it, again and again.

Layla was officially a water dog.

I initially guessed it had to do with her thick red merle coat: Perhaps she was hot. But her love of the water ran deeper than that. Layla was smart, a herder at heart who kept close watch over her flock. In the water, I think she felt free. Watching her splash and yip, it was like she was reborn, a puppy once more.

Layla’s love of swimming got me in the water too. It wasn’t long after that fateful trip to the Mulberry that we had our first human child, a daughter. By that point, I’d given up on coaching and had hopes of one day becoming a writer. I wasn’t sleeping much, but a nice long swim with Layla always helped clear my head.

I came to love the water so much that I wanted to live by it. That’s why, as soon as my first novel sold, I was officially in the market for a lake house.

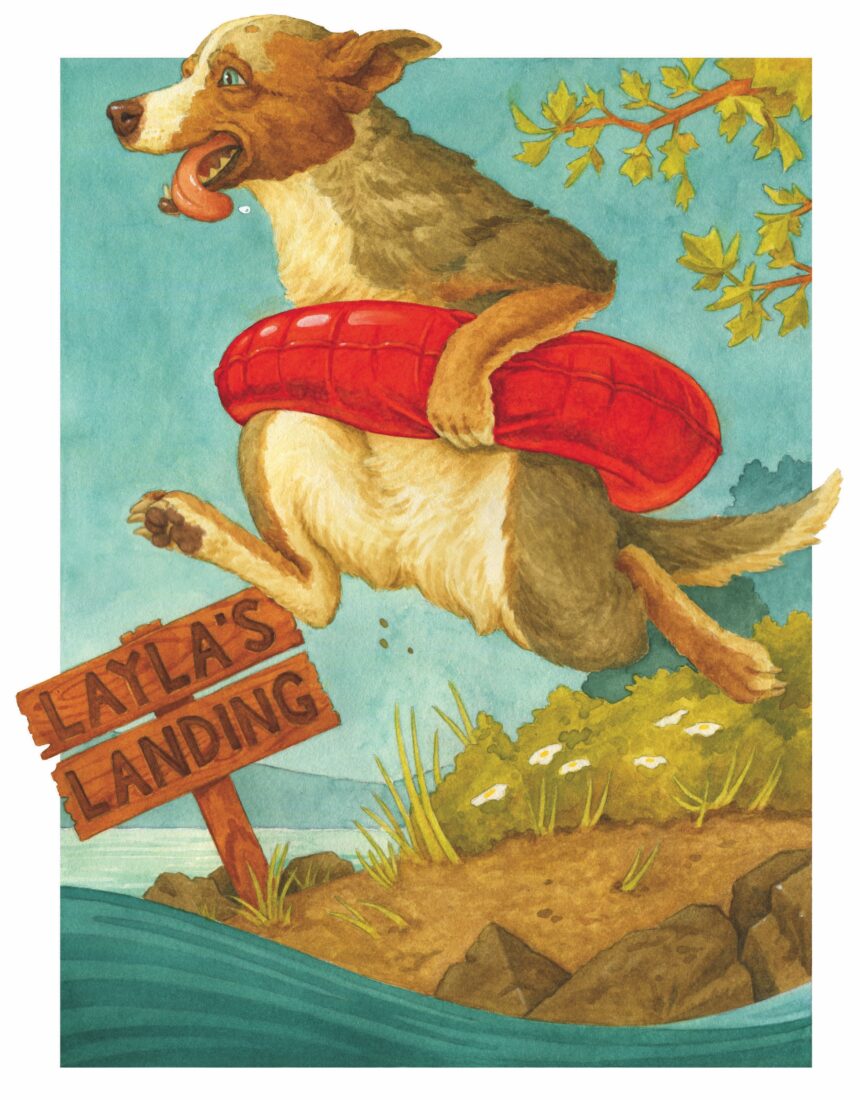

When we moved into our home on the banks of Lake Dardanelle, northwest of Little Rock, we named the place Layla’s Landing. By then, Layla’s and my routine had already changed. Gone were the field houses and locker rooms of our youth, replaced by the solitary existence of an author and his dog. Layla spent her days on the floor beside my desk. I’d write until lunch, then we’d both go out and swim. Five straight years of this, the life I’d always wanted, and then it came to an end.

I found a tuft of Layla’s fur on the dog bed—the one I still can’t bring myself to put away—just before I sat down to write this essay. She’s been gone six months now, but I keep discovering pieces of her: a faded orange life jacket, a gnawed-down bone, the baby-blue collar that sits on my bookshelf.

Two days before she died, Layla refused to get in the water. That was strange enough for me to take her to see the veterinarian. He talked of surgery, the chances of removing the mass he’d found in her abdomen, but what about her kidneys and the fact that they were failing?

Layla endured her remaining hours better than anyone expected. She ate. She drank. On the final evening of her life, right after we’d finished supper, she even got up and sniffed for scraps.

Her heavy breathing roused my wife and me in the middle of that same night. We moved her into the living room, dog piling around her favorite chair (the one that nobody, not even my daughter or son, will sit in to this day). I slept on and off until I heard Layla get down from the chair. I awoke in time to see her walking toward the kitchen. When her legs gave out, when she collapsed flat on her belly—I knew what was about to happen, what was happening already.

I keep thinking back to that moment; how, if she hadn’t gotten up, I might not have either. There’s a saying about how dogs prefer to die alone. But many think it’s a survival instinct, a way to safeguard their pack because their corpse could attract predators. Which would mean, even as she took her last breaths, Layla was still trying to protect us.

But she didn’t die alone.

Layla passed with her head in our hands and our tears in her fur. She departed surrounded by the two people she loved more than anything else in this world, and she did it gracefully.

Even in death, Layla was perfect.

She gave us an hour alone with her before the kids got up. We covered her with the same blanket we’d wrapped her in that night we brought her home from the Harps in Marshall. We held each other. We cried. When the kids came into the kitchen, we told them the truth. Staring down at their own mortality, they were confused. I was confused and broken and wondering why I wasn’t crying more.

The tears came when I started digging, tearing away at the dirt just up from the bank where we’d swum together too many times to count. It was still dark out. I wasn’t wearing gloves. I wanted to feel every shovelful, and I did. I cried more in the hour it took to dig that three-foot hole than I have in the past decade. When I finally reached the bottom, I climbed in. I stood in the place where Layla is now, and I cried some more.

Burying her was the hardest part, carrying her already stiff body down from the kitchen, down all those steps to the hole I’d just crawled out of. The blanket pulled away from her snout as I laid her to rest. That’s when I really lost it, when I saw those beautiful blue eyes for the last time.

I got it together enough to ask everyone to share their favorite Layla story. To this day, I cannot remember a single one. The kids dropped daffodils, a tennis ball, and a squeak toy onto the remains of our beloved pet, the dog we so often called “our first child.” And then we said goodbye.

As I began to fill in the grave, I kept fearing Layla would wake up. I kept thinking we had made some terrible mistake. I was so lost in my chore, my thoughts, I didn’t realize the rest of the family had walked back to the house. I just looked up and they were gone.

That’s how it felt. How fast it happened.

I stared out at the lake, waiting to hear a splash, a yip. A faint pink glow rimmed the eastern horizon. My writerly mind grasped for metaphors, some sort of symbolism about a new dawn, a new day that would help ease the pain. But there was no getting around the truth: For the first time in the whole of my adult life, I was completely and utterly alone.

I stepped into the water and started to swim.