“I was in Tipitina’s, in New Orleans, one night. I overheard drummer Eric Bolivar joke, ‘Here comes the fifth member of every band.’ I thought it was funny, but also really flattering. I respect the men and women that I photograph so much. I want to tell their story, and that’s what I try to do in my portraits.” —Michael Weintrob

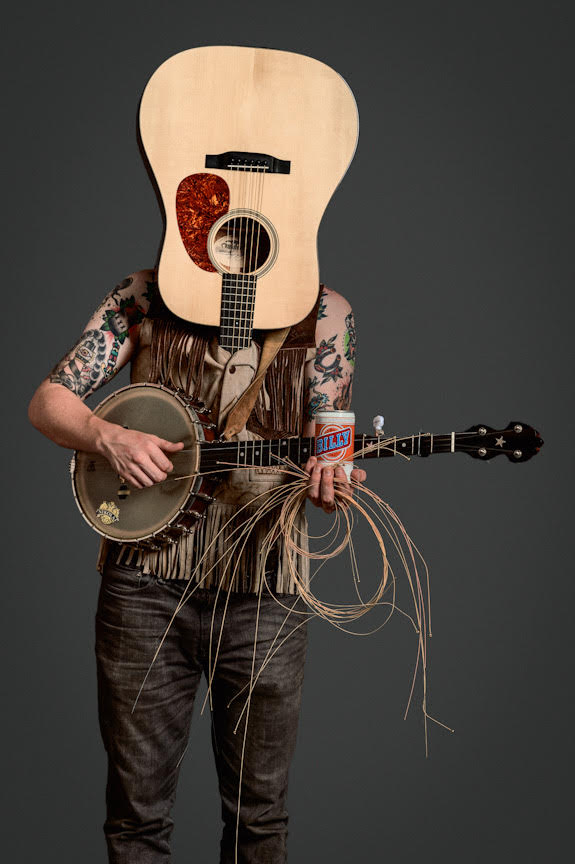

Michael Weintrob’s portraits are simple, yet provocative: He places a single subject against a soft, charcoal background, then leans into the props of their stage personas, asking a drummer to pull on his rhinestone jacket; requesting a banjo player adjust her iconic, cat-eye sunglasses. The accoutrement, instrumental and otherwise, lend humor and color, and just a hint at each musician’s identity.

And, that’s the most a viewer gets—a hint—in the Nashville photographer’s first coffee-table book, Instrumenthead, published in 2017. For the series of 368 portraits, he obscured the faces of the world’s most famous musicians with their instruments. Costumes, lighting, props, and surrealist nods give clues as who is behind a drum or a bass—say, Mickey Hart, drummer for the Grateful Dead, or Tina Weymouth, the bass player and cofounder of the Talking Heads. Yet, no caption provides certainty. Readers of the book, which won “Most Outstanding Design” at the Independent Publisher Book Awards that year, were left to guess—that is, until now.

Weintrob recently published the reprise to Instrumenthead—titled Instrumenthead Revealed—with those same 368 artists exposed, in the exact same order as the original book. Sold independently or as a set with the original, the collectible piece of table art both appeals to music lovers and testifies to Weinstrob’s remarkable, enviable career.

The photographer now lives and works in Nashville, but he was born in Birmingham, Alabama. He recalls an early interest in cameras. “I found a photograph of me at thirteen, taking a self-portrait in the mirror,” he says with a gentle laugh. “I was that kid at summer camp, carrying around a point-and-shoot.” His father gave him an SLR at nineteen, and, while attending Colorado State, Weintrob landed his first gig, shooting at a venue in Fort Collins. He worked his way up as a live music photographer, eventually freelancing for illustrious places and publications, including for two of music’s most recognizable names: the Red Rocks Amphitheatre and Rolling Stone. But he wanted to push his own limits, and decided to move to Brooklyn in 2003.

“I never took a class, but I had amazing mentors in New York,” he says. “I was really interested in portraiture, but I knew nothing about it. I had editors tell me, ‘Your live concert shots are as good as it gets, but if you want to be a serious studio photographer, you’re going to have to study.’” He spent years slowly sharpening the requisite skills of the world’s best studio photographers, from brainstorming out-of-the-box ideas to developing the ability to genuinely relate to his subjects on a deeper level.

Then, “In 2000, I was hanging out backstage with the Derek Trucks Band,” Weintrob remembers. “I said to the bassist, ‘Can you put your bass down your shirt?’ He did it. I wouldn’t say that was a lightbulb moment to making Instrumenthead, but it was the moment I realized a musician would do that if I only asked.”

And so he began ruminating on a series. “An instrument is a part of a musician’s identity,” Weintrob continues. “It’s an emotional, beloved item. Sometimes, in the case of Bootsy Collins’s star-shaped bass, or Dolly Parton’s big blond hair, the instrument or the look is as famous as the musician. I wanted to bring those things forward, and then to leave fans the joy of guessing.”

By 2007 or 2008, Instrumenthead began to take shape, but the undertaking from there, understandably, took years. Busy, scattered musicians would have to be wrangled into a studio—either in his town or in their own. He began making phone calls, to everyone from agents to assistants to the musicians themselves, including Victor Wooten of Béla Fleck and the Flecktones and George Porter Jr. of the Meters, offering free promo shots in exchange for their time in a studio.

“I’d describe my style as whimsical,” he says. “Everyone has the ability to be a kid again, and on the shoots, we’d have a really good time.” He convinced the musicians to stick guitars, banjos, keyboards, and more down their shirts, secured with a tight belt. “You are intimidated by the value of these instruments,” he admits. “We’ve never broken one, but I did crack a lens diving to catch a guitar once.”

Weintrob plays with whimsy and surrealism often. He dyed sugar cubes bright blue for a shot of Sugar Blue, the Grammy-winning harmonica player who sat in with the Rolling Stones for Emotional Rescue. Bootsy Collins, formerly with Parliament-Funkadelic and James Brown, went on to front and play bass for a group called Bootsy’s Rubber Band.

“I asked him to toss hundreds of them,” Weintrob says of the little office supplies, which he captured with the snap of a shutter as they fell like confetti. “I think about a musician’s overall identity,” he says, “and I want a way to have fun with that. The rubber bands and the blue sugar cubes—these things just made good sense to me.”

Not every shoot, however, came easy. Not every instrument can easily be suspended in front of a face. “The first time I ever hung an instrument from the ceiling was at Preservation Jazz Hall in New Orleans,” Weintrob recalls. “‘Uncle’ Lionel Baptiste was elderly and a little weak. He couldn’t hold a drum over his face, so I got the idea to hang it. We hung a coat hanger from an electrical conduit, and I sat him on a bench beneath it. From that moment, I began hanging instruments, using Photoshop to take out the wires in the final print.”

Weintrob’s connections with the artists he photographs has not only translated to these two art books, but also to intimate musical performances. In the summer of 2020, when venues were shuttered due to the pandemic, he turned his Nashville studio into a virtual concert venue and released five concerts a week for four weeks. The events helped to crowdfund Instrumenthead Revealed. Coming in 2023, Weintrob is planning to put on more of those kinds of immersive experiences around the books, from live shows inside galleries to signings at music festivals. Even better: “For Instrumenthead Revealed, a portion of the book sales will benefit the New Orleans Musicians’ Clinic, which provides social services to the local musicians there,” Weintrob says. “They’ve given me so much. It was only right that I give back.”

Jenny Adams is a full-time freelance writer and photographer, most often penning pieces on great meals, stiff drinks, and the interesting characters she meets along the way. She lives in New Orleans, with a black cat, a spotted pup, and a Kiwi-born husband. Right now, she’s working on a (never-ending) horror novel, set in the French Quarter.