Grandma Mary Alice and I crumbled the stale cornbread into her dented stockpot, our fingers eroding the chunks into fine silt. The corn oil she had coated the pans with days earlier turned her hands to onion skin as we worked, the blues and pinks of her veins shining.

We slipped in the sautéed onion and her secret ingredient—half a bag of Pepperidge Farm dried stuffing. She never actually called it her secret ingredient, but I have to imagine it was. Who would admit to stacking their cornbread dressing with store-bought? But Grandma got married in 1948 and had her two boys in the fifties, the postwar Jell-O mold years when saving a little sanity with a shortcut became a matter of course—a status symbol, even. I never asked her why she did it. Adding the Pepperidge Farm felt mostly natural if a little mysterious, like when the cows in the pasture just beyond her kitchen window all stood facing the same direction.

Grandma lived to host the Brown family—birthday dinners, Christmas brunch, the New Year’s good-luck meal, hog jowl and all. But she treated Thanksgiving like a sacrament. Before she retired, she would take the whole week off from her secretarial job at the brick company and spent days making lists and schedules so everything—the turkey, the dressing, the giblet and boiled egg gravy, the creamed corn, the mac and cheese casserole, the real cranberry sauce, the canned cranberry sauce, the dinner rolls—was perfectly timed.

Over the years, she took me, her oldest grandchild, the one with her same blue eyes, wry humor, and righteous temper, under her wing in the kitchen and just about everywhere else. Mary Alice and “Little Mary Alice” read Little Women together, laughed at The Golden Girls and Designing Women together, and cooked together, her teaching me how to make tea cakes and mashed potatoes and eventually, her dressing, the dish that more than any other we revered as a totem on the table each November.

Grandma had grown up in the textile mill village of Dunean, in the Upstate of South Carolina, and perhaps not a little of her hospitality developed out of spite. Her home economics teacher at the high school there once asked Grandma’s class to make up a menu for a dinner party. Teenaged Mary Alice planned and considered. She proposed an ambitious lineup: let’s say something like a chicken liver paté, followed by a green salad and a leg of lamb, capped with a chocolate torte. Her teacher scoffed. “Someone of your background will never need to know how to make a meal like this,” she said, and Grandma burned. She kept that slight in her pocket, turning it over until it became as smooth as a river stone, relating it to me again even as other memories faded. I showed her, I could see her thinking. Except we never really did eat anything that fancy at Grandma’s, unless you counted the cranberry congealed salad with crushed pineapple she also made on Thanksgiving, which not a few of us did.

The pastel flowers on Grandma’s thin housecoat blurred as she spun to the counter where the turkey rested in its pan, a rich amber liquid pooling beneath it. She plunged a dipper into the juices, skimming up bits of skin and fat and loose meat and sloshing it all into the stockpot, stirring in more and more until the cornbread fairly squelched.

She leaned her head over the mixture and sniffed, then tilted her head back to stare at me through the bottom of her readers. Her eyes glistened, their surface a flat reflection since her cataract surgery—Dad teased her that she looked like one of the Children of the Damned. “Tiiiiiiime to taaaaaaste!” she would say, dropping into a basso profundo. She trembled a teaspoon into the mush and gummed a bite. Add a little more salt and pepper. And sage, too. Again and again till it was right.

We poured the raw dressing into the buttered casserole dish, all the way to the top, smoothing it perfectly flat with the back of the spoon, the craggy stuffings of food magazines anathema. Into the oven it went, 375 degrees for thirty or so minutes. Then we would bring it out and scoop a shallow hole from the very middle to taste for doneness, smoothing the dent flat again so no one would be the wiser.

We squeezed the finished dressing into an old picnic basket with her address sticker on the bottom, the one she used to carry deviled eggs and potato salad to church potlucks. I picked up the treasure and side-winded to the door around her recliner, where she sat and worked crosswords and the Jumble and the Cryptoquote, and then waddled with it across the street to my parents’ house. Grandma would be over in a few minutes, after she drew on her eyebrows and pressed an Estée Lauder lipstick to her lips, after she combed her hair, what was left of it her one vanity that remained, her standing appointment on Wednesdays to have her curls set the only reason besides Sunday services she still got behind the wheel of her old gray Buick.

For years, we ate two Thanksgivings—lunch at Grandma’s, then supper at our other grandmother’s, our stomachs bloated and cramping. There was a certain relief when both women ceded the day to my parents to host. Once we combined the meals, Grandma’s dressing would sit next to Grandbunn’s on the kitchen island. Grandbunn made hers very thin and very dry with lots of sage, because that was the way Billy, her longtime boyfriend and our surrogate grandfather, said he liked it. We never knew what was the chicken and what was the egg in that situation. Did she continue to make her version because Billy actually did like it, or did Billy hear us praising Grandma’s, and so told her he preferred hers to spare her feelings? We didn’t want to hurt her, either, so as we spun around the island, filling Mom’s Pfaltzgraff with food, we’d all take a giant hunk of Grandma’s, and as tiny a slice as we could get away with of Grandbunn’s.

As we sat down at the table, one more tradition had to occur before we could dig in. We glanced at each other, and then at Grandma, anticipating the moment. Then Grandma would cast her eyes down at the dressing, sigh, and say dolefully:

“Well … I really don’t think it’s very good this year.”

It became something of a family joke, the faux modesty she wore like a crown of thorns. But when I started helping her with the dressing, it freed her to finally soak in the praise, a shared achievement with her only granddaughter.

When Papa went into a nursing home, Grandma began to spend Thanksgivings there instead. No matter how much she loved roasting the turkey, she loved Papa more. And so I took over the making of the dressing completely, lugging my own shinier stock pots and mixing bowls to her house to use her oven, her Corningware better left in the wooden cabinets to time and the spiders and the mice nests and the vines that crept in from God knows where. I didn’t like to look too closely at the grime and grease and dirty dishes piled in the sink. It was too painful to confront her living there by herself, unable to keep up with it all.

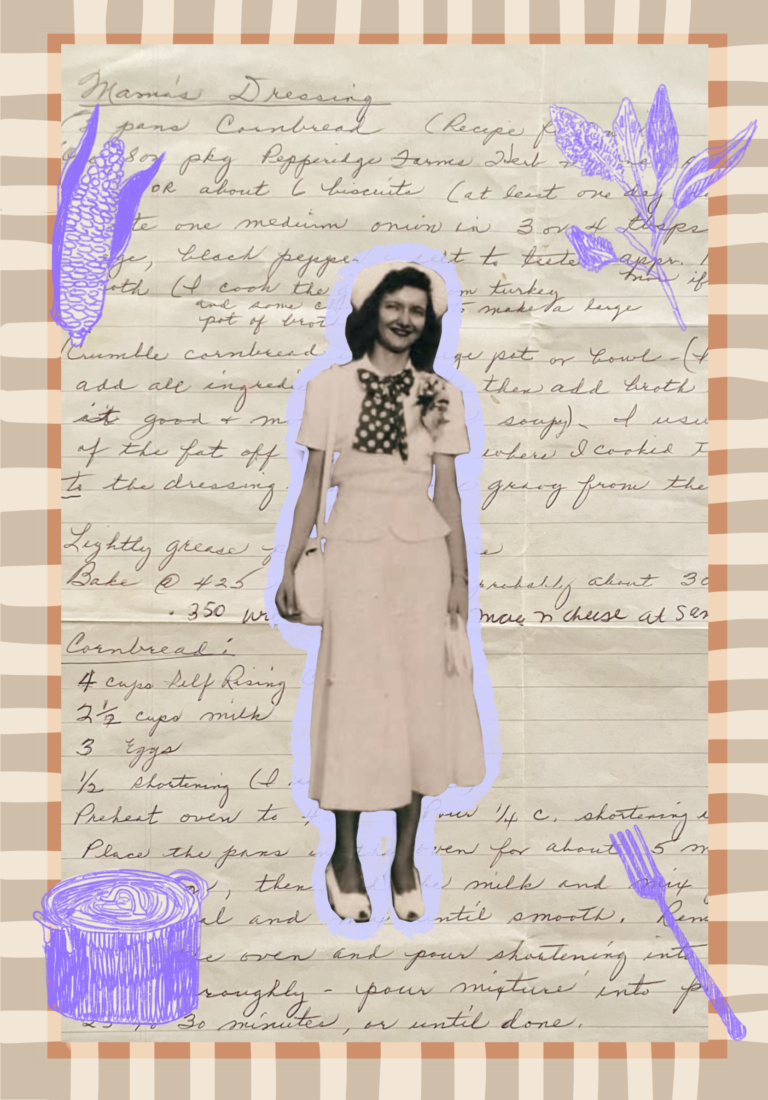

After Papa died, she mostly watched as I cooked, though we would always taste for seasoning together. Then she died, too, and Thanksgiving has never been quite the same. But every year since, I spend the weeks leading up to the holiday doing my best impersonation. I drag out the laundry basket and begin to fill it with the pots and pans I need to cook in Mom’s kitchen, slowly, methodically ticking my checklist as I go. Three days before, I get out the buttermilk and cornmeal and unfold the notebook paper where long ago Grandma wrote out for me in her secretary’s cursive the recipe for her cornbread and dressing, consulted so many times now it’s gone soft at the creases.

I keep meaning to do something with that paper. Frame it before it disintegrates, before the ink fades. But what of the steps not recorded on those lines? What of the bond and pride and teasing shared between two people, so alike?

On Thanksgiving morning, when I crumble that cornbread, and pour the stock, and season and taste, I close my eyes like it’s a prayer. A meditation. And for just a moment, she’s there.

My oldest nephew, Grandma’s oldest great-grandchild, turned eight in September. Old enough to stand on a stool and stir a pot, which he loves to do. He has blue eyes, and long eyelashes, and loves learning, just like his Aunt Amanda. My family sometimes calls him “AJ”—Amanda Junior. Perhaps this is the year that I invite Amanda Junior over to help Little Mary Alice. To learn the unwritten steps that make the dressing more than just a dish.

Amanda Heckert is the executive editor of Garden & Gun and the editor of the magazine’s book Southern Women. A native of Inman, South Carolina, she previously served as the editor in chief of Indianapolis Monthly and as a senior editor at Atlanta magazine. She lives in North Charleston with her husband, Justin, and their dogs, Felix and Oscar.