I have known Andrew LaMar Hopkins since he was seventeen, and watched as he’s become the internationally known artist and force of nature that others meet today. Originally from Mobile, and a longtime student of French antiques, Creole culture, and real Champagne, Andrew creates paintings that blend historical accuracy with the cheeky fun of courtesans and cocktail parties. Last year, in his adopted hometown of New Orleans, the Louisiana State Museums hosted a major exhibition of his work at the Cabildo, titled with his catchphrase Creole New Orleans, Honey! Then recently, he moved to Savannah and began painting Gullah Geechee subjects. “His art is about life lived in peacock glory, dazzling, crazy,” the critic Jerry Saltz says. “It has this great sexuality.” (It’s also selling as fast as he can paint it.)

Paris is his happy place—he’s been going there for more than a quarter century and delights in its nooks and crannies. Paris has been my happy place for longer than Andrew has been alive. So it felt like destiny last year when we met up in the City of Light for the first time and I attended a gallery opening of his during my annual sojourn. This year, we rendezvoused again to go to a flea market. While most antique lovers know of the massive markets to the north of the city at Clignancourt, Andrew and I prefer the smaller weekend market just beyond the southern edge of the city at Vanves. Those on the hunt descend at dawn for what is called the déballage, or unpacking. Andrew and I, who each admit we do not need another thing, arrived at a more civilized hour when vendors were finishing up and likely to discount. Andrew would initiate discussion in English. I’d then take over in French to negotiate. By our third purchase, we’d fine-tuned our tag team. On three occasions, I even ended up with gifts, or lagniappes, as they would have been called in New Orleans, where we first met.

The next day we ate at Le Récamier to gloat over our treasures. After a lengthy and exceptionally liquid luncheon, we parted, vowing that the “dream team of Vanves” would reconvene same time next year. But not before we chatted about his life in the art world.

You were born in a Creole city, have spent a fair amount of your life in another Creole city, and now you live in a third.

At the beginning of COVID, I got a place in Savannah, and recently permanently moved there. I realized it has a parallel culture, of Gullah Geechee. In the Gulf South, you say voodoo, and in the Lowcountry, it’s hoodoo. It’s a rabbit hole that I’m going down and painting as I learn.

Marie Laveau is your Creole icon. Do you have a Gullah Geechee one?

A person I have painted a few times is Dave the Potter, from South Carolina. I love his work. He made some of the biggest pottery pieces in America at that time, as an enslaved person. But he signed his work. He wrote poetry on his pieces.

I’m doing my Gullah Geechee paintings based off reading, but I really want people to tell me about their culture. With my Creole work, people would tell me about a story in their family, and I tried my best to create it on canvas. The past is not always beautiful, but I do feel the ancestors talk through me to have another voice in this modern day and age. I’m dedicating my whole life to bringing these people back. I hope I’m doing them justice.

How did painting become your medium?

As I was growing up with not a perfect childhood, it was my way of creating another world. It was like, I love antiques, I love architecture; as a person of color, let me paint people in this reimagined, aristocratic way. And then as I got older, I learned about free people of color and realized, oh, there were a small group of people that were like this during that time. I was also paying homage to these people who could no longer speak.

What are some of your favorite things to do in Mobile and New Orleans?

Oh goodness, one of my favorite things, which is a little silly, is Morrison’s Cafeteria. We have the only Morrison’s left in America in Mobile. Oh, I can smell it. I get the same meal, chicken fingers with honey mustard sauce. And honey, if they don’t have the rutabaga when I get there, I’m not a happy camper.

I love going to antique shops in New Orleans. Of course, I love Lucullus. I’ve gone there since I was sixteen. And Renaissance Interiors in Metairie. But I cannot buy one more piece of furniture, so I have to buy something small.

Where do you like to paint?

In my bedroom. I love being at home, surrounded by my antiques. I like to think that my lifestyle brings the nineteenth century alive. I buy what I paint in my paintings—pottery, porcelain, silver—and use them when I entertain. This is what people did in the past. You didn’t toss something in the microwave and eat off paper plates and throw away utensils. Someone’s coming to my house, they’re going to be sitting down at a tablecloth with napkins from the nineteenth century and Champagne glasses that are two hundred years old. It’s a ceremony!

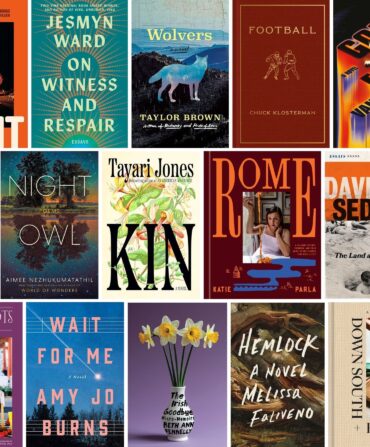

Read more about the South’s new slate of artists, curators, preservationists, movers, and makers in Art’s Rising Vanguard.