Like banana pudding and the boat shoe, the Junior League is one of those things that didn’t start in the South but feels like it should have. Founded in New York City in 1901, the women’s volunteer organization maintains a Southern stronghold, with about half of its 295 international chapters based in the region. Among those, the Junior League of Charleston (JLC) can’t claim the most membership or the longest history (superlatives that belong to Dallas and Baltimore, respectively), but the South Carolina organization has played a unique role in its home city: that of historian and cultural steward.

It was a role the chapter was born to play. With twelve founding members, the JLC formed in 1923 during what’s known as the Charleston Renaissance, a period when tourists awakened to the picturesque old city and historic preservation became the issue of the day. The Junior League naturally took up the mantle, says Amy Jenkins, the JLC’s current executive director. One of its members, Frances R. Edmunds, went on to become the founding director of the now-venerated Historic Charleston Foundation in 1947.

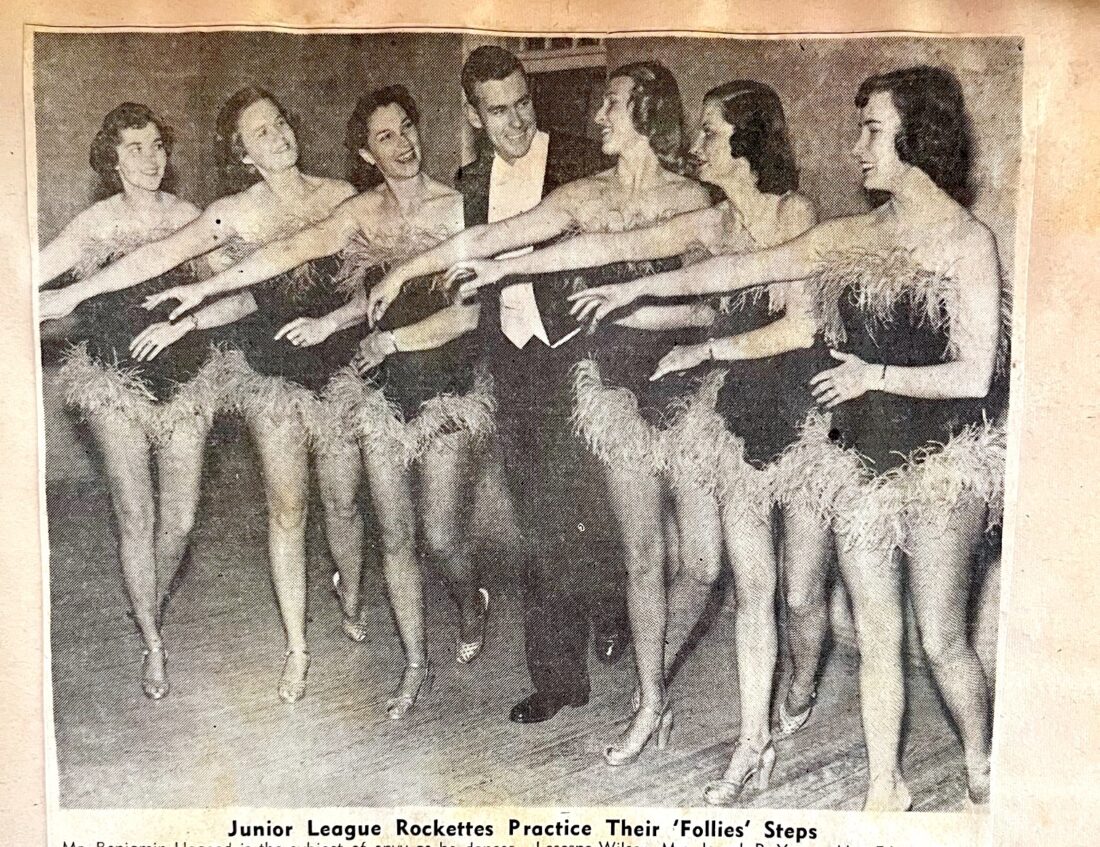

When tourists arrived in the Holy City, they encountered not just antiquated buildings but distinct culinary flavors. In 1950 the JLC published Charleston Receipts, a spiral-bound community cookbook, to raise funds for a speech and hearing center. League members and their families—including a teenaged Vereen Coen, now eighty-nine and honorary cochair of the JLC’s centennial (along with Nella Barkley)—tested each recipe in a Julie & Julia–like undertaking. (Alongside Cotillion Club Punch and Carolina Housewife Wedding Cake, there are dishes instructing the reader to saw open a turtle shell or reel in a couple dozen large-mouth bass.) In 1957, local Junior Leaguers served the book’s cooter soup to Queen Elizabeth II.

The oldest Junior League cookbook in print today, Charleston Receipts hasn’t altered its original text, an artifact of the Jim Crow era in which Gullah verses are transcribed by white authors with bylines that start with “Mrs.” But as an early, encyclopedic catalogue of Lowcountry cuisine, the book still informs chefs across the country. “We feel Southern food, and particularly Charleston food, is really the basic ingredient for all successful endeavors in cooking,” Coen told the Southern Foodways Alliance in a 2015 oral history.

The JLC’s publishing forays never lacked for civic pride. In 1965 the group produced Across the Cobblestones, a guidebook to historic sites and local flora that skewed romantic in its prose. “Charleston, curled up in the pointed toe of a slim southern peninsula, has preserved more antique beauty than any other city on the Atlantic coast,” one passage reads. “Bolstered by a proud if tumultuous past, she is a cosmopolitan city…”

They distributed educational pamphlets to local schools; Jenkins recalls encountering one as a third grader in the 1970s. “When one of our old buildings is torn down or defaced, a bit of American history belonging to us all vanishes,” went the opening of a 1960 edition of the JLC booklet Our Charleston. The author then made a prescient acknowledgment: “We cannot keep everything that is old for we live in the present and not in the past.”

Today Charleston’s food and tourism credentials are well established, and its current “renaissance” is that of a rapidly expanding metropolitan area. (From 2020 to 2022, the region’s population grew three times faster than the national average, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.) The JLC attends to permanent residents in its partnerships with food banks, children’s hospitals, crisis ministries, and hurricane relief efforts. Last year the organization distributed more than 120,000 diapers through a diaper bank—and still fell far short of demand, says Kitty Robinson, a past JLC president who is cochairing the centennial celebration with another past president, Betsy Clawson. “Charleston is growing by some thirty-five people a day, so there’s plenty of need,” she says.

Robinson herself moved to Charleston in the seventies, transferring her Junior League membership from Montgomery, Alabama. For her first volunteer role in town, she served as a docent in a historic home on East Bay Street—the start of a long career in preservation that would include eighteen years as CEO of the Historic Charleston Foundation. With current and recent members in high posts at the Gibbes Museum of Art, the Charleston Museum, the Charleston Horticultural Society, and other institutions, the JLC remains a force in the local cultural scene.

But asked to name the project of which they’re most proud, both Robinson and Jenkins cite the Dee Norton Child Advocacy Center, a support center for victims of child abuse. The Norton Center (then the Lowcountry Children’s Center) opened in 1991 and has since served more than 35,000 Charleston-area kids through physical and mental health exams, forensic interviews, therapy sessions, and professional training. And like Charleston Receipts, a cookbook created for philanthropic purposes, it began as a simple idea between Junior League members.

“One hundred years ago there were twelve women who got together under the auspices of bettering the community,” Robinson says. “The whole purpose of the Junior League is about serving, and serving well.”