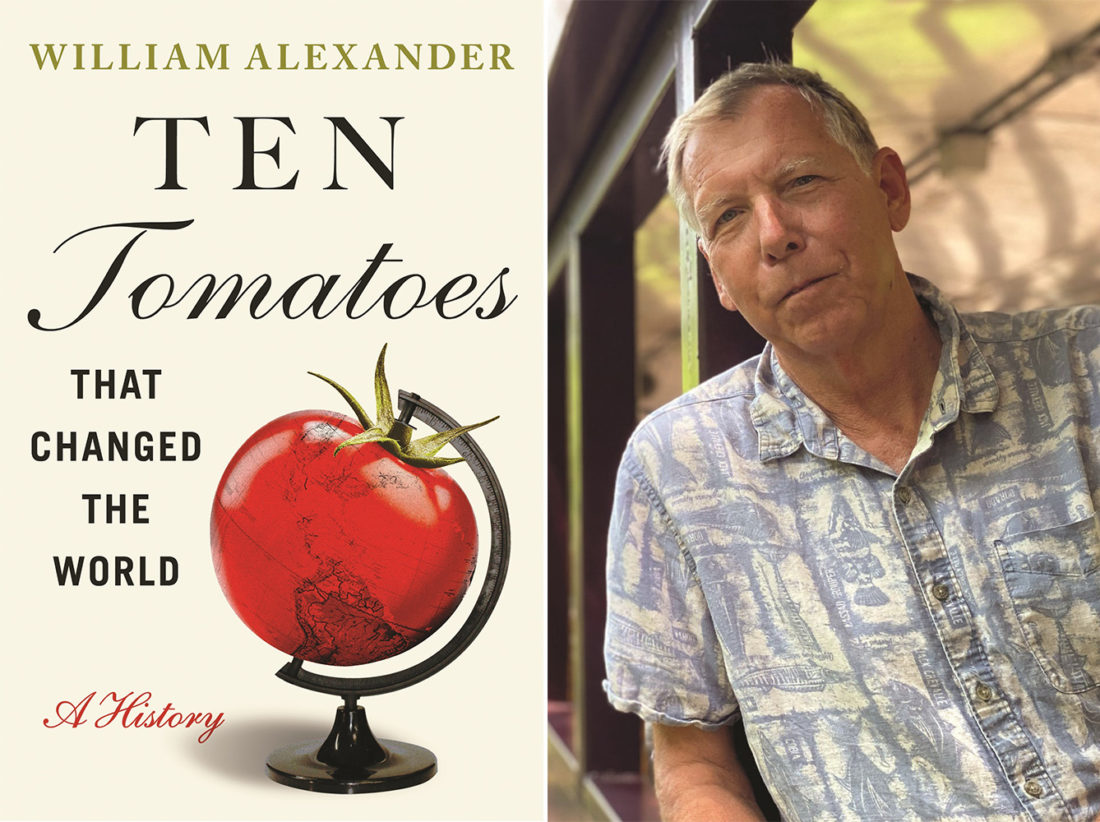

Although native to South America and grown in more than 170 countries worldwide, tomatoes feel very Southern. For many people below the Mason-Dixon Line, a bite of a juicy, vine-ripe tomato tastes like summer, and the vegetable has made itself at home in Southern gardens and kitchens since the 1600s. “The American tomato is a Southern tomato,” says the New York Times bestselling author (and self-proclaimed tomato guy) William Alexander, whose new book Ten Tomatoes That Changed the World tracks the vegetable’s unlikely rise through world history. Today, Americans eat roughly one billion pounds of tomatoes a year, and, as Alexander says, we have the South to thank for a lot of that. Here’s why:

The South introduced tomatoes to the rest of the country.

“There are two possible paths for how tomatoes got to America,” Alexander says. “We know the first place they were grown on American soil is on the Georgia and Carolina coasts, and they were either brought here by Spanish settlers in that region who had come up from Florida and the Caribbean, or they were possibly brought in by English settlers, though I don’t think that’s likely.” Unlikely, Alexander explains, because although European cuisine famously incorporates tomatoes today, the New World enjoyed the vegetable long before the Old. “When they first arrived in Europe from Mexico, they weren’t eaten for hundreds of years. They were thought of as poisonous. So, in the 1600s when they were being grown in the South, Europeans weren’t eating them yet. That’s why I like the theory that the Spanish settlers brought them north.”

In fact, Southerners ate tomatoes long before they were popular.

Other parts of the world hesitated. Since tomatoes are members of the nightshade family and a close relative of the belladonna, a sweet and alluring yet highly toxic fruit, when sixteenth century Spanish explorers brought samples back from Mexico, most Europeans turned up their noses. And while tomatoes slowly crept their way into the hearts and plates of Europeans, it wasn’t until the nineteenth century that they found their immortal place alongside Italian pasta. “For centuries, Italians were eating pasta with lard as a sauce,” Alexander says. “The pigs were being bred for prosciutto and the lard was a byproduct. Farmers changed pig breeds to get a leaner prosciutto, but that lard wasn’t as good, so they started looking for new ways to eat pasta. Hence the tomato.”

As soon as tomatoes arrived in America, however, the South began devouring them. “This could be from the influence of enslaved people, including household cooks who had eaten them in the Caribbean,” Alexander says. “Tomatoes also have such a strong tradition in Gullah Geechee culture and cuisine. They weren’t being eaten at all in the North at this time.” Southerners also tended to be more comfortable with garden pests than their Northern counterparts. “When you’re growing tomatoes, there’s no getting away from hornworms,” Alexander says of the harmless yet once widely feared caterpillar. In Ohio in the 1860s, a newspaper article claimed an eight-year-old girl “died in terrible agony” from the spittle of a hornworm. “Southerners, who already knew about tobacco hornworms, though, were less squeamish about it.”

Spurred by events in the South, the United States Supreme Court decided a case on the definition of tomatoes.

“In 1893, tomatoes were sent to the U.S. Supreme Court to determine if they were vegetables or fruits,” Alexander says. Because tomatoes grew first—and often better—in the South than the North, antebellum plantations grew them in large quantities and shipped them north. When war broke out, Northerners looked to boycott Southern goods and started importing produce from the Caribbean and elsewhere. “After the Civil War, the Southern fields that Northern growers had contracted with wanted business back, so they got Washington to impose a 10 percent tariff on vegetables imported from outside the U.S.,” Alexander says. The only problem: since tomatoes have seeds, botanists classify them as fruit, not vegetables, and therefore, the North argued, the tax did not apply. “In 1893 that case made its way to the highest court in the land. The case was Nix v. Hedden, but I call it Tomato v. Webster’s,” Alexander says. The court read the definition, heard two witnesses, then voted 9 to 0 that a tomato is a vegetable because it’s eaten like a vegetable. With the tariff firmly in place, the price of boycotting Southern tomatoes became too high, and Northerners once again turned to Southern growers.