Sporting

Baptism By Quail

A hunter journeys to the famed Red Hills in pursuit of the storied bobwhite, those doing everything they can to bring it back, and his own family’s legacy

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

The hunting party and a wagon of dogs head out in the morning for the quail woods.

If humanity is born of clay, mine is surely red. I was born in Northeast Georgia, and any Georgian who knows the business end of a shovel knows the grip red clay exerts on the roots within it. Nonetheless, I left rolling hills and pastures for three peripatetic decades spent wherever the Marine Corps sent me before settling on the black mudbanks of a North Carolina tidal creek. I come by my restlessness honestly, through my mother’s family, a fact amusing and perplexing to my paternal grandmother, Imogene Parker. “That’s the Russell in you,” she would say, laughing. “Y’all like to go places!” She recognized before I did my instinct to redraw the borders of home.

So it was I found myself driving north on Miccosukee Road outside Tallahassee, Florida, a patch of red earth from which my familial roots stretch northward. My hunting companion, Seth Vernon, a saltwater fly-fishing guide and naturalist, and I had driven to the Red Hills—436,000 rolling acres of longleaf and wire grass–covered red clay between Thomasville, Georgia, and Tallahassee—in an all-day push from Wilmington, North Carolina. We arrived in the remnants of a torrent driven by fifty-mile-an-hour winds. Rafts of Spanish moss lay draped across the road, torn from meandering live oak limbs before the limbs themselves were hurled through power lines now sagging along the shoulder. In the absence of electricity, my headlights rendered the famous canopy road a sopping tunnel so dark I felt as if I were at the bottom of a hole, wondering if all the darkness in the world had fallen in atop me.

In the final few miles, we sought only to avoid electrocution while seeking a private quail plantation called Martha, where I’d received a generous invite to my first quail hunt. Given the hazardous weather, our arrival felt somewhat ominous. But having left Tallahassee seventeen years prior, after four happy years, it was also a sort of homecoming.

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

Pete, an English pointer, gets a noseful of quail.

Quail played an outsize role in my grandmother’s life, and Betty Ann Campbell Russell played an outsize role in mine. My great-grandfather Louis “Bub” Campbell was a dogman from Fitzpatrick, Alabama. Trained in the art by his father, he was hired as the kennel manager for one of the Red Hills’ most venerable quail plantations, just a long morning’s walk from Martha, in 1922. Bub rose to helm more than 11,000 acres of prime quail land, owned by Northerners for whom the word wealthy did not suffice. He and my great-grandmother Annie Reid Campbell had two girls when Annie died young in 1928, and my grandmother Betty Ann grew up assisting in hunts on horseback, with dogs carried by wagons and silver service luncheons midhunt. As a result, she forever valued fine shooting and the bobwhite quail. Marriage took her to Northeast Georgia, where Bub’s death in 1948 left her enough to buy 600 acres of farmland and build a home decorated in quail feather hues. She raised five children there, and in no small part, me.

The woman I called Nana gifted me a deep love for the natural landscape, but the joy she felt in hearing the multisyllabic call of a bobwhite never gripped me. There were and still are quail to be found in North Georgia, but I suppose the Red Hills left Nana ruined for anywhere else, and I grew up a desultory hunter, occasionally freezing in a deer stand or waiting on a flight of teal in a jon boat. Hunting quail as Nana knew it was a thing too remote for comprehension; part fantasy, part history, as otherworldly as the wealth of the people she shadowed growing up.

While generous people across the South have offered to share their deep love for the bobwhite with me, I have always politely and appreciatively demurred, hoping to one day hunt something more than just the bird. Missing Nana as I have since she passed in 2021, I wanted to understand her through Colinus virginianus, the northern bobwhite quail, by hunting the same ground as Nana and Bub. Somewhere in the whirring explosion of a Red Hills covey, I hoped to find answers to half-formed questions, a heavy expectation to place on birds so fragile they average an eight-month life span.

It would be wholly disingenuous to pretend the Red Hills quail culture is not one born of immense wealth. Nor could one assert that much of modern bobwhite conservation does not come from the same source. It’s easy to feel jealous until you appreciate that much of the incredible amount of money poured into saving the bobwhite comes directly from the pockets of people expecting no return on the investment beyond quickened heartbeats and lightened souls. As one private land manager with deep roots in the Red Hills said to me, “There’s no money made in this. Just the opposite. We’re pouring barrels of cash into the ground here. This is simply about love of the birds and the culture around them.”

In Conserving Southern Longleaf: Herbert Stoddard and the Rise of Ecological Land Management, historian Albert G. Way notes, “By the 1920s the Red Hills was set to develop and profit from a new identity. No longer was it a place of the failed southern plantation, trying to hang on to the Old South. It was now known as the domain of the wealthiest, most refined class in America.” The new owners were primarily Northern industrialists who converted a swath of Georgia and Florida into a place of leisure, albeit one propped up by rebranded versions of inequities found in the Old South. Central to their retreat was quail hunting, a pastime they approached with an industrialist’s eye for process and an aristocrat’s eye for culture and refinement.

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

One of Tall Timbers' banded quail; hunters on horseback return after the day's hunt, trailed by the quail wagon; Chris Craver with George, a four-month-old English cocker from a recent litter.

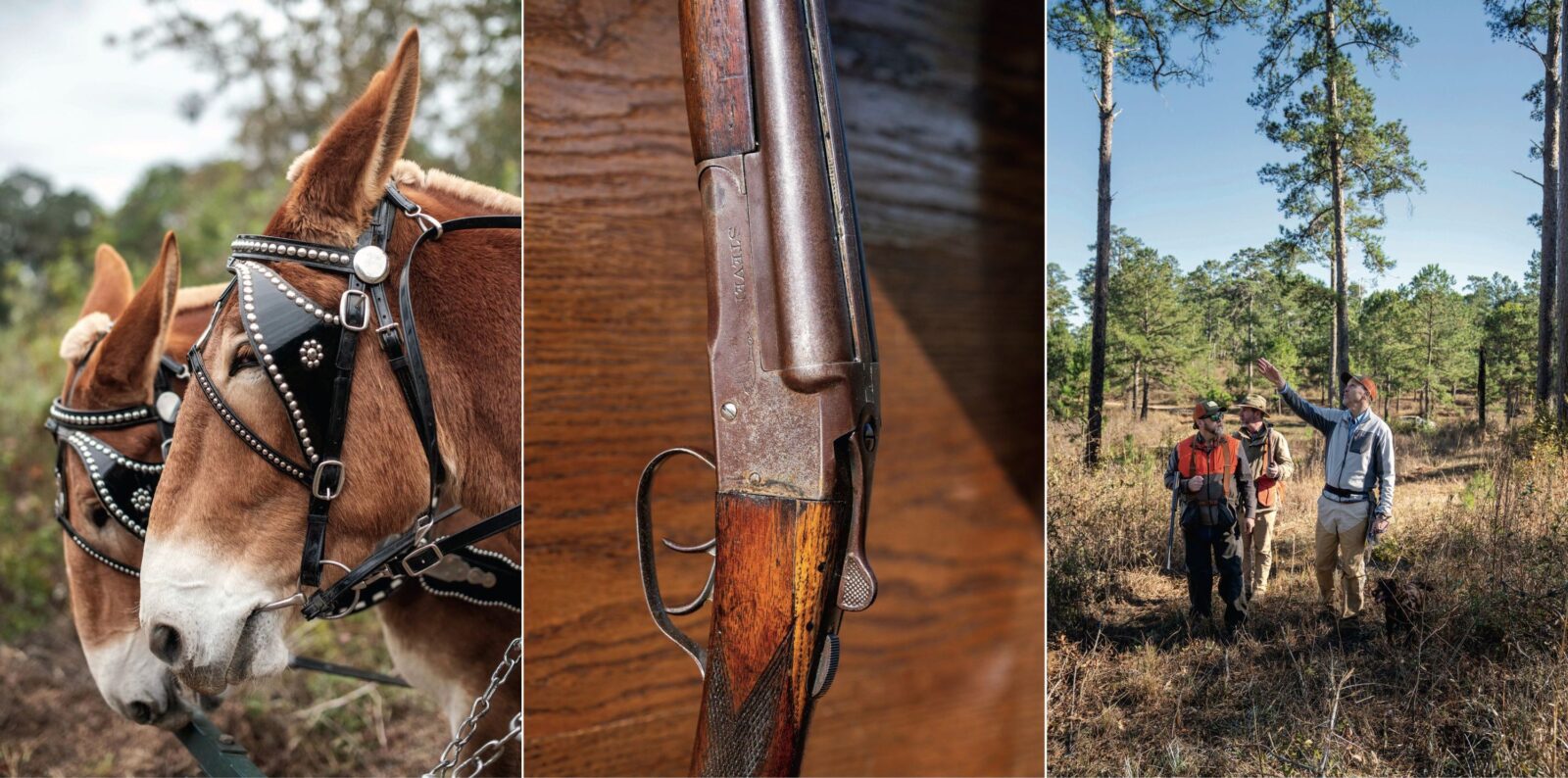

Process belonged to a man named Herbert L. Stoddard, ultimately the voice of quail conservation and Red Hills land management. Men and women well versed in maximizing systems efficiency appreciated his cyclical approach, managing land largely in the ways in which nature and native people had been doing forever. Looking to European aristocracy for cultural guidance, the new arrivals brought mule-drawn wagons and horseback hunting to their thousands-of-acres accumulations. Today, at Martha and other Red Hills properties, landowners, managers, and dedicated staff passionately live, love, and preserve both Stoddard’s brand of careful land management and the finer aspects of quail hunting.

There is an entirety to the experience of hunting at Martha, found in the way that, as soon as you think, “I wish I had…,” that thing is there.

After spending a comfortable night in a beautifully appointed and thoughtfully stocked guesthouse, I walked to the lakefront main residence carrying a bounty of gas station honey buns and beef jerky I’d brought along to share. On my arrival, chef Todd White obviated my plan with thick-cut bacon cooked crisp enough to stand on end, coarse-ground grits with pimento cheese, delicately fried eggs, and a vegetable hash for those less carnivorous than I. As I consumed a second round of the best muffins I’ve ever eaten, Martha’s head butler, Kelvin Sheffield, arrived. With a smile, a handshake, and an inquiry about our guns, he directed us to a trap range adjacent to the house to warm up for the day’s hunt. I shoved a third muffin into my mouth, and Vernon and I walked to the range.

Sheffield was waiting with boxes of shells, including some for Nana’s Stevens .410, a century-old gun I’d had restored by the Sylva, North Carolina, shotgun savant Raymond Bunn. I’d also treated myself to a new 20-gauge Beretta 686 Silver Pigeon for this pilgrimage, but I’d put only a single box of shells through it. Under Vernon’s more experienced eyes, I broke clay until he declared me ready for quail, and we set out to meet the hunting party in Martha’s Jeep.

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

Wagon mules Mike and Ike; the author's Stevens .410, handed down from his grandmother; chatting with Bill Palmer at Tall Timbers.

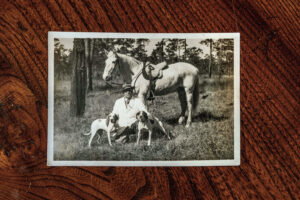

Driving red clay roads, tires muffled by a carpet of longleaf needles, I let my mind drift to a photo almost one hundred years old. In it, my great-grandfather Bub wears the white jacket of the hunt staff. A cigarette dangles insouciantly from the corner of his mouth, his eyes hidden deep in a fedora’s shadow. He kneels in front of a white horse, a steadying hand on each of two English pointers, dogs so tautly muscled I can almost see them quivering from a century away.

Steadiness is the mien of the manager. Waiting for us in a clearing at the top of a hill, Chris Craver, the manager at Martha, defined the word.

Standing at the center of his staff, horses, and a wagon full of dogs, Craver wore a white jacket and a field hat in which Bub would have been comfortable. After welcoming us with a broad smile and firm handshakes, he moved with the precise economy of an orchestra conductor, ensuring our guns and gear were loaded on the wagon, and that we had sufficient shells in appropriate gauges and knew where to find more, and introducing us to Noah Stump and brothers Meusiul and Jose Gonzalez, the men responsible for the horses, dogs, and wagon. It felt as if everyone was in on a secret I had yet to discover, one they were excited to share.

Setters and pointers soon tore through bluestem and broom sedge, rapturously captive to the impulse of their noses but ever attentive to Craver behind them. Vernon and I followed him at his flanks, all of us mounted on horses with coats clipped close above their shoulders. The wagon brought up the rear, three merry English cockers perched atop, paying close attention as we proceeded into some of the most carefully managed quail habitat on earth.

I missed the first quail at which I ever shot. Craver, pushing through the brush on foot, had called me forward to one of the carefully planned shooting lanes checkerboarding Martha, granting the day’s first shot to the neophyte. I felt as if all the world were arrayed behind me, sharing the moment. The birds exploded upward and outward, and I emptied both barrels at a bobwhite crossing left to right, a clean miss. From her heavenly reward, I could hear Nana’s exasperated “Oh dahlin’! What a horruh!”

In truth, I was as much cheered as disappointed by the escape of a bird against which the odds are so stacked by weather, predation, and constitution. Nonetheless, when the time again came to pull the trigger, I snapped the Beretta to my shoulder and killed a bird streaking toward the expanse of an oak. A “Good shot!” from Craver was shockingly gratifying given my three decades in a profession built around shooting well. At “Send me Millie!” one of Craver’s English cockers sprinted down the wagon’s dog ramp, a buff-colored perpetual engine seemingly powered by the frantic metronome of a stubby tail. Millie delivered to hand my first bobwhite, and I quietly thanked her and the bird, the delicate heft of its body belying the weight of my emotions.

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

The author’s great-grandfather Louis “Bub” Campbell.

For men accustomed to gas station coffee and public land hunting, a post-hunt lunch under the live oaks on a lush green carpet of perfectly tended grass brought a succession of gilded surprises—mint juleps in sweating silver cups, Todd White’s Boursin penne, three-bean salad, roasted corn, fall-off-the-bone ribs accented by pickled okra, onions, and quail eggs, and red velvet cake. In coming to Martha, we had intended only to leverage the owner’s generous offer of the land. But in retrospect, that was an unintentional slight to the people who spend so much of their time contemplating how to make that spent by Martha’s guests ever more sublime. In appreciation, I made good use of a hammock thoughtfully placed near the crackling fire, nodding off in an ample breeze moderated by a blanket.

“I just want people to leave and they’re like, ‘Man, my God, I’ve never seen any place like that, never been anywhere like that, never experienced anything like that,’ from every aspect,” Craver said. “From eating dinner, to hunting, to walking around, to seeing my dogs.”

Throughout our day of hunting, Craver ensured we shot no covey more than once, watered and rotated the pointers and setters, made sure the cockers rested on the wagon, and always maintained careful awareness of the geometry of hunters, staff, and dogs. Watching him, I felt closer to Bub, a man with a reputation for high standards. Riding to the hilltop from which we’d begun, crossing a landscape in which my forebears were so invested, I hovered on the edge of elation and tears alike. In that golden hour, with the Spanish moss spun from fire, coveys bursting forth from grasses ablaze with sunglow, it felt as if every wrong in my world had at least momentarily been righted. As Craver said, “Man, I’m just so blessed to be here.”

The Red Hills contain four-hundred-year-old longleaf pines, contemporaries of long-fallen behemoths that once grew from the Carolina coast to Texas. Standing in the Big Thicket National Preserve north of Beaumont, Texas, a few years ago, I was stunned by how much it looked like the cypress swamps and sandy longleaf forests in southeastern North Carolina. Then I realized I was standing at the western remains of a once gargantuan forest that stretched clear to my home on the East Coast. It’s as if we’d had a shelf filled with irreplaceable books and decided to burn them, keeping only the bookends. Fortunately, the volumes that tell the story of the Red Hills, and thus much of America’s remaining native longleaf pine forests, survived. That is in no small part thanks to the work of Herbert Stoddard.

Stoddard arrived in the Red Hills in 1924, the same year Nana was born. Bub was a thorough notetaker, his angled lines of pencil scratch recording covey sizes, weather, terrain, and frank assessments of the shooting abilities of landowners and their guests. In 1946, he wrote of being “asked to ride over and meet Herbert L. Stoddard.” He continued: “I was glad to get the opportunity. Mr. Stoddard immediately started asking me questions about quail.”

Stoddard and Bub became friends over theories of habitat development, predator management, and fire, topics about which Bub was sufficiently expert for Stoddard to repeatedly reference him in his seminal The Bobwhite Quail: Its Habits, Preservation, and Increase, and in his autobiography, Memoirs of a Naturalist. In the century since, the work with which Bub assisted Stoddard has grown from a sapling into Tall Timbers, a Tallahassee-based nonprofit and research organization dedicated to quail and the lands upon which they live, and the fire that underlies the health and welfare of both. At two facilities in the Red Hills, the 9,000-acre Livingston Place and the 4,000-acre Research Station, Tall Timbers seeks to “foster exemplary land stewardship through research, conservation and education,” particularly through a focus on science that is the very opposite of cutting-edge.

Tall Timbers president and CEO Bill Palmer is an evangelist for the role of fire in land management. “We need the hunters and the nonhunters to stand up for good fire stewardship…that’s one hundred percent the key,” he told me as we sat on the edge of Lake Iamonia, under the arms of a live oak older than our nation. “Many wildlife schools don’t teach anything on fire, when fire is the fundamental ecological issue. Whether you’re a trout fisherman and you want clean water, or a bird hunter, or an elk hunter, it all ties back to prescribed fire.” As for managing different types of land for quail, Palmer said, “Whether it’s burning, timber management, supplemental feeding, or predator management, you have to understand the system.” To see that understanding in action, he invited Vernon and me to hunt with him.

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

English cockers Millie and Shep wait to be called from the wagon.

Even with the graciousness that comes with a day of Martha’s refined hunting, we had been shocked the night before to find ourselves too tired to do much beyond wipe down our guns and melt into the couch, recounting the day’s moments. Five hours later, we bade each other good night, having finally eaten the honey buns and jerky. It’s what I used to feel after running hundred-mile ultramarathons; deeply satisfied, completely wrung out, but unable to sleep for desire to relive the moments with people who understand them. Tall Timbers promised a similar result, packaged differently. If hunting Martha was a deeply meaningful opportunity to connect with the elegant style in which my ancestors hunted, the Research Station offered a connection with the wild birds they pursued.

I again felt on the precipice of a great secret. But part of Palmer’s message is, there is no secret. “The properties that have the resources—they have the best quail hunting in the world right here, no doubt about it…[But] if you have a decent bird dog, you can go find wild quail even today. The essence of the sport is the bird and the dog, and then, a gun.” And so, guided by a French Brittany named Picon backed up by a precocious young English cocker named Pilar, we walked into 4,000 acres of pine-filtered sunlight seeking Tall Timbers’ purely wild quail.

Photo: Andrew Hyslop

A successful day at Martha.

A hunt behind a dog like Picon is a rapid tour of miles of habitat; a brisk walk among brambles and grass, followed by a hard push through wild coveys that know staying put or chirruping through the underbrush is a safer bet than a starburst from cover at forty miles per hour. At Martha, Vernon and I shot a “buggy limit” of a mix of wild and early release birds. Twice I doubled, killing a bird with each barrel on the covey rise. At Tall Timbers, I wasn’t even sure I saw the birds before they were gone from sight. Of the two I killed, both were long trailing shots owing more to rifle marksmanship than the instinctive shots of a true shotgun shooter. Even Vernon, more familiar with a double gun than I, could down only two quail.

Hard-won birds are satisfying birds, and ours contributed valuable data, which Palmer duly recorded. My second quail bore a tiny leg band identifying it as part of a research project ongoing since the 1920s. The bird’s information would go into a ledger supported at its inception by Bub and Nana, and now including my name. Over the last thirty years, Tall Timbers has banded and radio tagged around 60,000 birds across its two properties. The information gathered helps explain how and where quail grow, reproduce, nest, and die. Now threaded on a piece of raffia, the band hangs from a tine on the antlers of a deer skull in my office, adjacent to the bell I rang as we lowered Nana at her funeral, a going-home tradition in my family. I think she would appreciate that quail’s memorial hanging next to hers.

I had come the Red Hills seeking answers about a bird, a landscape, and a culture, and where I might fit among them. I had experienced generosity and graciousness, and I felt I had come to understand implicitly the romance of dogs running fully immersed in their purpose. Most of all, I now knew the emotions inflamed by the frenzy of a covey rise; the all-nerves-firing-at-once storm of sound and beating wings and shouldering and firing and feathered missiles rag dolling to the earth.

Listening to Bill Palmer, I felt in myself the stirrings of the passion I’d seen on display, and a burgeoning optimism that there is a future for these birds beyond the Red Hills. “There is hope,” he said. “I feel like there’s a growing interest in conservation by the millennials, through interest in food and other reasons. I do think that if people can get on board with the right message, we have an opportunity with a lot of state and federal dollars going to conservation, and prescribed fire in particular…that the potential for quail in the Southeast is pretty good. There will be places, like we’ve proven we can do here, where somebody says, ‘I’m going to go bird hunt today.’”

In the Drive-By Truckers song “Ever South,” Patterson Hood ruefully growls about “the way I bang my head against my daily circumstance.” I’ve too much Scotch-Irish in me not to respond to the promise of an uphill fight, and even with the resources of the ultrawealthy, the focus of Tall Timbers, and the passion of a hunter with a dog and a gun, preserving the bobwhite quail is indeed fighting uphill. But I have always been given to pursuits of the blood and spirit, pulled to opportunities to dance on the line between finding or losing myself. If the passion inspired by quail is a gentle, beautiful madness, it is one to which I give myself over completely.

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with Bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book. All books are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.

Related Stories:

Trending Stories: