Sporting

Farewell to an Unforgettable Gundog

A hunter’s fitting send-off to a loyal, if sometimes hardheaded, Boykin spaniel

Illustration: NATE SWEITZER

The day after putting my dog Pritchard down, I started keeping a journal, a place I knew I would need to log my emotions when others had tired of me lamenting her loss. Within the first few pages I wrote, “The shadows and dreams are the toughest parts. The pair of pants on the floor that at three AM look like P. Or the shadows the late-afternoon sun casts on the couch. Not that you hope she’s suddenly still alive, but for a nanosecond she just is.”

Carolina Magic’s Pritchard, a Boykin spaniel, was born on December 12, 2009. From the day I picked her up, I dreamed she would be a gundog. As it turned out, this was not a shared vision. Gundogs are quiet and steady in the blind (nope), gentle on the birds they retrieve (is that the sound of bones crunching?), and eager to please (ha!). My Pritch was hardheaded. Or as one of the country’s most respected gundog trainers told me early on, “She’s just too damn opinionated.”

But my wife, Jenny, and I, both loyal to a fault, loved that dog. She was our first child. Weren’t we all complicated? And besides, there wasn’t room in the house for a second dog. So Pritchard and I got to work, training in the early mornings and cool evenings. For the dreaded hard-mouth issue, I’d have Pritch sit on a bench while she held a plastic water bottle in her mouth. Whenever I heard the crinkling caused by the pressure of her teeth, I’d stroke her neck and say, “Easy. Easy, girl.” Eventually, I replaced the bottle with bumpers and birds.

We competed in hunt tests and mostly did poorly—though I still proudly display a ribbon she won at the 2012 Boykin Spaniel Society National Field Trial. I also introduced her to upland hunting, where her natural drive and great nose fell more naturally in line with the task at hand, mainly to find the quail and flush it. On new-moon tides of fall, a friend and I would row the Lowcountry’s coastal feeder creeks, pushing marsh hens from the last remaining clumps of spartina grass the tide hadn’t covered. Often Pritch would smell the birds before we flushed them, whining and, occasionally, jumping off the bow before the shot in her excitement (a “free swim,” we called it). Her stubborn nature was a plus, though, as she always pushed through dense marsh and waterlogged wrack to get the bird. And boy oh boy, did we love a good duck hunt.

So when I was left with a bag of ashes in a cheesy cardboard box from an animal that had not only been my constant companion in the field for more than twelve years, even if imperfectly, but also adjusted wonderfully to the addition of two children to our pack, I felt like I owed it to my girl to spread her remains at the places she loved most. Inwardly, I also hoped that each stop on the road tour would carve away at the pain and allow me to grieve at my own pace. Make loss something I could handle. I chose three spots.

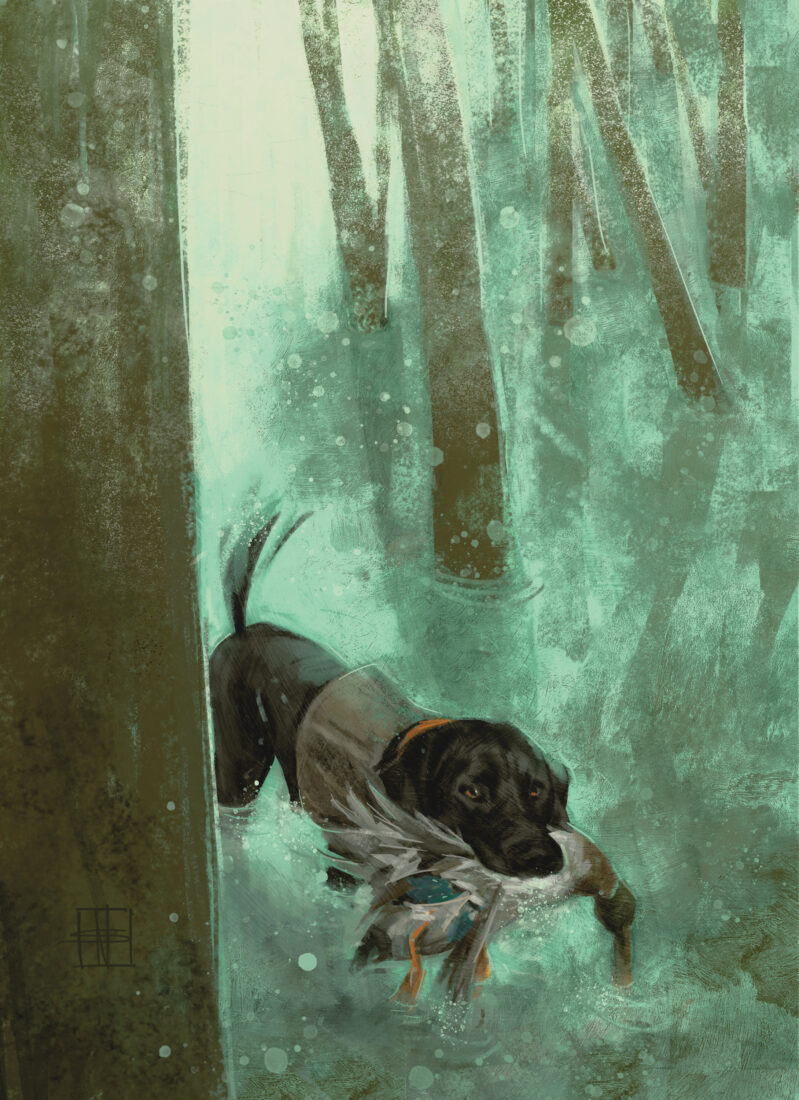

The Woody Swamp

The hunting club I belonged to for most of Pritchard’s life was far from a bird-dog paradise, but it had a spot Pritchard and I came to know well: a small section of thick swamp that cut through some hardwoods and sometimes held wood ducks. Located near Ridgeland, South Carolina, it was the site of Pritch’s first duck retrieve. As we’d made our way in at 5:15 a.m., it felt like an impenetrable jungle, and I used the blinking red light of a cell tower to keep my bearings. She was young and unsteady. Once we reached our spot, I looped a lead around a tree to keep her from wandering off while we hunkered down and waited. She didn’t yet know that remaining still gave her a better chance of doing what she loved, getting a bird.

As they often do, the woodies flew in at the edge of first light, just after shooting time. We heard them coming, first their distinct call— daweeep—and then the whoosh of wings, a few seconds before we saw them. I instinctively lifted my gun and fired. When the drake hit the water, I let Pritch go. My heart soared as she beelined toward the duck, all those hours of training now culminating here. She came back to the hummock, dropped the bird on the shore, shook, and rolled in the leaves. I was ecstatic. She’d done it. We’d done it. On the way home, I pulled off at a McDonald’s. I bought each of us a sausage biscuit, and we ate them sitting on the bumper of my Jeep. A tradition born.

Illustration: Nate Sweitzer

Though we’d hunt every inch of that swamp over the next duck seasons, I spread her ashes on a foggy morning at the spot of her very first retrieve. I hadn’t been to that exact hummock in years, but using a cell phone pic I’d snapped that day, I found the tree we had crouched near. After pouring her ashes, I rocked back onto the ground and sat for a long time, listening to the swamp come to life.

The Santee Delta

When we were lucky enough to get an invite to hunt a stunning spread of former rice fields, usually once a year, no other obligation got in the way. It was here, in South Carolina’s Santee Delta, that Pritchard did her finest work. Though as usual, there were some bumps. On our first hunt, we arrived the night before just as dinner was ending and a raucous cocktail session was beginning by the fireplace, stout retrievers lounging within the warmth of the blaze. As I joined the fray with a stiff bourbon in hand, Pritchard started circling atop the Oriental rug beneath the taxidermy and Audubon prints, then promptly squatted and took a dump while I stood nearly frozen in disbelief. “Who brought the Boykin?” someone asked with a chortle.

But the land was so vast and wild that even an unruly Boykin spaniel did little to flare the wigeon, gadwall, and teal. When my hunting partner and I connected, Pritchard charged through the soft mud and shallow water with abandon, chasing down windblown birds and cripples. On one memorable occasion, she was pushing through the muck for a teal when a bald eagle appeared above her. For a moment, I wondered if the eagle intended to carry my Boykin off, but thankfully it swooped down on the teal and a few yards later dropped it. While the eagle circled above, we cheered the brown dog on as she completed the retrieve.

On a late January hunt, after a perfect morning beneath a pluperfect sky, I pulled a pill bottle with some of her ashes from my duck bag and announced to my hunting buddy that it was time. I don’t know if the green-winged teal that suddenly appeared in the dekes, the only one we’d seen that day, had any idea of the ceremony at hand, but we took it as a sign. And later, we raised a bourbon toast to my gal.

Pritchards Island

I named her after one of my favorite barrier islands. Pritchards sits just south of the beach community of Fripp Island and north of the highly developed Hilton Head. It’s uninhabited and, like most barriers, as shape-shifting as a summer cloud. The wind and storms take, and the doldrums give back, but are much stingier with their remittance. As a kid, I beached my jon boat on this island and explored every sandy inch of it. It was here I saw my first rattlesnake in the wild, sunning on a November day in the fold of a dune by some sea oats. Here, too, I hooked—and lost—my first ever bull redfish, its giant tail the last I saw of it as the three-foot-long fish rolled in the waves. Then it surged toward the horizon, peeling the remaining line off my reel until I heard the dreaded pow! as it snapped. I dropped to the sand and cried.

Pritchard took to the island with gusto, joining Jenny and me in the surf as we continued to chase those redfish and rolling in whatever the waves could toss up on the sand, as long as it smelled nauseatingly awful. When our kids were born, we took them here for their first adventures, and they ran wide open after their dog, chasing her through tidal pools and romping in the white water of the surf.

We were all together when we took her there one last time. Everyone knew the mission, though the kids still wondered why Pritch’s ashes were gray and not the brown of her fur. We picked up shells and driftwood that caught our eyes and found a spot behind the dunes that seemed perfect. Two scraggly pines and a palmetto stood watch. We dug a hole and poured the remaining ashes into the sand while we all told her what we loved about her and that we would miss her. Rosie remembered how soft she was. Sam added that he was glad there were no thunderstorms (which she hated) in doggy heaven. We used the shells and driftwood to decorate the area and hammered a small piece of her blaze-orange hunting collar onto the palmetto.

Illustration: NATE SWEITZER

“What happens if the waves come over the dunes?” Sam asked.

“They will eventually,” I told him. “But Pritch will always be part of this island. Just like she’ll always be part of us.”

Later, as I wrote the last entry in my journal, I noticed I had started writing on the front and back of every page as I neared its end, trying in vain to cram the stages of grief into a slim notebook.

“Apparently, I’m not keen on running out of space,” I wrote on the last page. “Just like losing a dog. We run out of space. We just ran out of space…Man, we loved you, P. More than you will ever know. Rest easy, gal. Please rest easy.”