Food & Drink

Marcus Samuelsson’s Memphis Joyride

A world-famous New York chef with a taste for the South takes a rib-sticking, pork-laden, soul-lifting spin through the River City

Photo: Squire Fox

From left: Chef Marcus Samuelsson and the authors hit the town in Memphis; A clamshell of Gus’s fried chicken for the road.

“I’m way more interested in B-sides than the hits,” Marcus Samuelsson shouts from the backseat of a 1950 Buick Roadmaster, above the wind whipping through rolled-down windows, the roar of the straight-eight, and Elvis braying “I Just Can’t Help Believing” from the chrome speaker. We’re cruising east on Lamar Avenue, past truck-repair yards and boarded-up churches, to the Memphis smokehouse Payne’s Bar-B-Q, and truth be told, we have no clue whether Samuelsson’s referring to something you listen to or something you eat. The chef has just been riffing about Eastern redbud, the lavender-pink buds spraying out on trees we’re whizzing past, a little-known food Native Americans foraged. He imagined them pickled in jars with a few lingonberries thrown in, behind the bar at his Harlem restaurant Red Rooster. But we take his easy drift from food to music as a sign that despite his having just landed from Gothenburg, Sweden, the night before, Memphis—whose lifeblood is music and food—is already working its magic.

Or perhaps it’s just pure Samuelsson. Fans of Red Rooster and its sister rotisserie, Streetbird (or any of his thirty-one other restaurants in places such as London, Chicago, Malmö, and Bermuda), know viscerally his celebration of the blurred lines of culture—to say nothing of his passion for the jump cut and the remix. Dishes from his kitchens can trip from Jamaican jerk to South Carolina grits to Korean kimchi, sometimes on a single plate, and knock you out with their elbows-deep deliciousness. From a chef born in Ethiopia, raised in Sweden from the age of three by adoptive parents, and with twenty-odd years cooking professionally in the melting pot of New York City, a certain boundlessness might be expected. But Samuelsson’s restless enthusiasm crosses many genres. He’s a voracious admirer of music and contemporary art (in his spare time, he paints; he differentiates Streetbird from Red Rooster thusly: “It’s the difference between hip-hop and jazz”). Not to mention his flair for sartorial fusions, mixing, say, Hawaiian-print jeans with a thrift-store cardigan and a broad-brimmed Aztec fedora.

Photo: Squire Fox

The group’s 1950 Buick Roadmaster.

Now forty-six, Samuelsson first landed in Manhattan in 1994, a twenty-three-year-old apprentice at the new-Nordic temple Aquavit. Within a matter of months, he’d risen to executive chef and the same year became the youngest ever to receive three stars from the New York Times. James Beard Awards and a brush fire of attention and acclaim followed, putting Samuelsson in line to earn the cookbook deals, TV gigs, and financial backing of a full-blown celebrity chef. He eventually settled down in Harlem with the woman who would become his wife, Maya Haile. And when he opened his first restaurant there, Red Rooster, in 2010, he turned to the story of American food—and particularly his travels through the Southeast—for inspiration.

But while Samuelsson is no stranger to the South, this trip marks his first visit to Memphis, a city he has long wanted to experience. And B-sides or not, with just thirty-six hours before he is off to John Besh’s Fêtes des Chefs charity event in New Orleans, we’re on a madcap run to take in the city’s culinary and cultural landmarks, which is how we end up easing the big Buick into the parking lot of the former gas station the Payne family transformed into a barbecue joint in 1976.

Photo: Squire Fox

The order window at Payne’s Bar-B-Q

A shroud of smoke hangs over the room’s dim corners, and when Samuelsson steps inside and sees Flora Payne at the far end of her galley kitchen, in front of the redbrick chimney, its sooty double doors folded back, he freezes. We watch in silence as she pulls a char-crusted pork shoulder from the pit, sets it on her chopping block, and rips into it with a staccato thock-thock-thock from her cleaver. She mops the pork shrapnel with a ropy red sauce, loads a mound onto a bun, then drops a scoop of bright yellow slaw on top. We order our own sandwiches and eat them outside, as best we can, slaw and sauce sliding down our forearms onto the hood of the car. Samuelsson marvels at the texture of the pork—tender, but shot through with crackling bits of bark, and spiked with a heat that puts to shame the pulled pork, “bastardized in Swedish cafeterias,” that he’d grown up with. And he’s never seen a barbecue sandwich garnished with a mustardy slaw in the Memphis style.

Photo: Squire Fox

Flora Payne (left) at work in the kitchen.

“All these nuances?” he says, between bites. “They’re what I love about Southern food. You only learn these differences when you travel, and a way for me to understand them better is to come here, to peel that onion. I consider all my restaurants research projects. I’m always learning, always a student.”

A flicker of a childhood memory—the pure joy Samuelsson felt when his late mother, Ann Marie, an Elvis superfan, doled out candy to her children to keep them quiet whenever the King appeared on Swedish television—was Samuelsson’s first connection to Memphis. And his mom taught all her children English through Presley’s music, so the city came to be elevated in his mind, symbolic in a way he says might be difficult for Americans to comprehend. Only later did he learn that in addition to being the birthplace of Southern soul and rock and roll, Memphis was a crucible for more tragic forces, as the site of the Martin Luther King, Jr., assassination and a place where the aftershocks of the fight for civil rights are still deeply felt. As a chef inspired by the South, cooking in Harlem, an epicenter of African American culture, Samuelsson felt he needed to experience Memphis.

Memphians willingly spool out the underdog clichés about their hometown—redheaded stepchild of Nashville, the team you always root for that never wins—and it’s true the city’s music-fueled postwar mojo was virtually extinguished in the wake of King’s murder and the folding of Stax Records in the seventies. But even today, as Memphis resurges as a creative force (the place where Bruno Mars recorded the 2015 Grammy Record of the Year, “Uptown Funk,” at Soulsville’s Royal Studios, and where Charles “Lil Buck” Riley danced a path from the New Ballet Ensemble in Midtown to an Apple commercial and international stardom), it’s not a town that trades in easy superlatives. Instead, it affords the space and time to find your own groove. Ask Memphians who’s got the best barbecue in town, for example, and they’ll demur: Depends what I’m hungry for. Shoulder sandwich? Ribs? Game hen?

Photo: Squire Fox

A fried-chicken beacon.

The evening before our trip to Payne’s, we pick up Samuelsson at the airport with a plan to mix Memphis’s past and future in a single night. We’re packing two Styrofoam clamshells of fried chicken from the sixty-year-old Memphis institution Gus’s and heading to a listening party at the recording studios of one of the city’s newest record labels, Unapologetic. James Dukes, a native Memphian who cut his teeth at the fabled Quad Studios in Times Square, returned to his hometown a couple of years ago to found the label. As we dig in to the Gus’s at the studio and settle in with Dukes and a handful of his artists—crooner Cameron Bethany, producer Kid Maestro, and rapper AWFM—Samuelsson is already having visions of hosting a showcase at Ginny’s, his music venue in the basement of Red Rooster.

Midsession, we meet another of the label’s collaborators, Christopher Dansby, known as PreauXX (pronounced “pro”), a soft-spoken man with pulled-back hair and computer-nerd frames. Dansby recently returned to the city from Atlanta and offers his own perspective on Memphis’s underdog character. “In Atlanta, everything is so fast and saturated,” he says. “You don’t have time to appreciate what you’ve got. We say we’ve got ‘humble hustle.’ We consciously use our humility to get things done.”

We’re reminded of those words the following day at our next stop after Payne’s, Stein’s (pronounced “steens”) Restaurant, a neighborhood meat-and-three Willistine Myrick opened forty years ago alongside her beauty parlor. When we show up just before noon, the room is packed; a line of doctors and nurses, linemen in coveralls, and church elders stretches halfway to the door. A long table of women spot Samuelsson, and he happily obliges them with selfies before tucking in to his plate of baked chicken, lima beans, and yams.

“Fascinating how pure this place is,” he says, pointing to the long unadorned wall where the diners are lined up. “There’s no music, no TV, no distractions—just the food and the people. It reminds me of the cafeteria next to the Volvo factory in Gothenburg, with the waxed cloths on the tables. The meats might be a bit different, but the honesty is exactly the same.”

Photo: Squire Fox

Samuelsson digs in to lunch at Stein’s.

Little do we know he’s about to experience a flavor even more familiar on the ride to our third lunch of the day. As we speed north on South Lauderdale Street, about a block after we pass Royal Studios—where, forty-five years ago, Al Green recorded “Let’s Stay Together” and “Love and Happiness”—Samuelsson screams, “Stop the car! Stop the car!” He’s out the Buick’s door before we can even pull to the curb, bounding into Hattie’s Grocery, a corner store with comely hand-painted lettering offering HATTIE’S TAMALE. He emerges with a paper sack full of cigar-shaped tinfoil rolls. Tamales are believed to have arrived in the Mississippi Delta in the 1920s with a wave of Mexican migrant workers, but the meat-filled corn batons were adopted readily by African American cooks, who substituted plain cornmeal for masa, used their own seasoning and fillings, and—in Memphis at least—replaced the corn husks with simple waxed paper.

“I’ve heard about these!” Samuelsson says. “But I’ve never found them.”

After the restrained seasoning of our Stein’s lunch, the tamales hit the spot—intense, chile-rich stewed beef embedded in a thin layer of supersoft cooked cornmeal. But for Samuelsson, it tastes even closer to home.

“This is doro wot!” he shouts, referring to the national dish of Ethiopia. “This is my home cooking! The cornmeal tastes just like injera bread.”

Photo: Squire Fox

The pit house at A&R.

As Samuelsson wolfs down his tamale, we warn him to save room for A&R Bar-B-Que, which, even in a superlative-shy environment, we are willing to vouch for as having the best ribs in Memphis. We can tell Samuelsson is skeptical, as he keeps rewinding and riffing on Payne’s: “That pit? Part art, part science, but you have to grow up in that to really know it. We talk a lot about authenticity, but people who are actually authentic don’t focus on it at all—it’s not a value, it just is.”

As we pull around to the parking lot in back, smoke is rising from the three stacks above the A&R pit house, and Samuelsson gets amped up all over again. We place our order and take the parcel outside, where he unwraps it on the hood of the car, eyeing the slab of ribs, burnished brown and glazed with a reddish sheen of sauce. “Would you look at this?!” he says in a raspy scream. “This is actual perfection!” He rips a rib from the rack and lights into a full critique. “Plenty of smoke,” he says. “I love the heat, too. It’s not fall-off-the-bone. It has a little bite-back, and I like that.” After stripping his first bone, he reaches for another. “When we got here, I didn’t think I had room for one more bite,” he says. “But this…?”

Photo: Squire Fox

Ribs from A&R Bar-B-Que.

Just as he’s speaking, an elegant woman with oversize round glasses, like a Southern Iris Apfel, rounds the corner of the building. “Y’all should be eating inside!” she says. She introduces herself as Rose—“the R of A&R”—Pollard. And when Samuelsson showers her with praise for the ribs, she summons her nephew, Damon Briggs, the pit master. Briggs leads us around back to the shed with three chimneys. He opens the rightmost set of carbon- and grease-baked iron doors to reveal racks of shoulders, whole bolognas, and ribs cooking over smoldering oak and hickory coals.

“This is it!” Samuelsson says. “Look at that! How long have they been in?”

“About an hour or two,” Briggs says. “These shoulders will be on overnight, though. Ten, twelve hours.”

“Who taught you how to do this?” Samuelsson asks.

“Just trial and error,” Briggs replies. “After thirty-four years, you kinda get used to it. I’ve been doing it since I was eighteen.”

“Thank you so much,” Samuelsson says. “You made our day!”

Photo: Squire Fox

Samuelsson with Rose “the R of A&R” Pollard.

A&R sits on Elvis Presley Boulevard, and with Graceland just a five-minute drive south, we decide to head toward it. The closer we get, the denser the boulevard becomes, with its plethora of strip malls, hotels, and chain restaurants, and Samuelsson grows quiet. His mother recently passed away, and rather than take the tour, we decide instead to pull up in front of the stone wall and linger in front, sitting on the roof of the car to better see the mansion in the distance. “I thought the house would be bigger,” he says. A woman from Kentucky introduces herself. She’s seen Samuelsson on TV and asks if she can take a photo of him. He says yes, but only if she gets in the picture, too.

Photo: Squire Fox

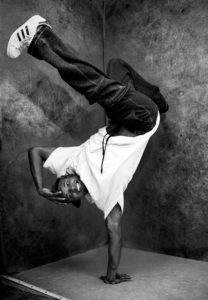

Break-dancer Anthony Allen rehearses at the New Ballet Ensemble.

After picking up a friend, Andria Lisle, a writer with a thirty-year career as a culture critic, radio-show host, and museum curator in Memphis, we head downtown, stopping along the way at the New Ballet Ensemble to catch a rehearsal. We tour the former home of Stax Records, now reborn as a museum and a music academy, and we pass Crosstown Concourse, an ambitious redevelopment of a million-and-a-half-square-foot 1927 art deco building that’s being converted to house apartments, shops, restaurants, and an art gallery. Lisle guides us past the Memphis Pyramid, and we skirt the well-trodden Beale Street before arriving at the National Civil Rights Museum, opened in 1991 on the site of the Lorraine Motel, where King was assassinated. On the second floor of the motel sits room 306, immaculately preserved—cups of coffee half consumed, ashtrays full, the bed linens turned down—just as it was when King stepped onto the balcony.

Photo: Squire Fox

Looking in at room 306 at the Lorraine Motel, part of the National Civil Rights Museum.

“It’s haunting to think about the amount of fear people had for a peaceful movement,” Samuelsson says, looking through the glass into the room. “But I’m also struck by the humility. Here was one of the most famous people in the world at the time, staying in this modest motel.”

That evening, we visit another landmark of the civil rights movement, Clayborn Temple, the enormous stone cathedral where striking sanitation workers in 1968 distributed I AM A MAN signs to protesters. After years of neglect, the temple is being restored for use as an event venue, and tonight it’s hosting the Young Collectors Contemporary Art Fair, where a couple of dozen artists are showing their work. Among booths spread through the vaulting tabernacle, we meet the fair’s founder, Whitney Hardy, a native Memphian who, like Christopher Dansby, recently moved back from Atlanta. “It’s a great thing that’s happening in Memphis,” Hardy says. “People who grew up here and moved away are returning with ideas and inspirations. I came back and said, ‘Hey we have just as much culture here—let’s highlight it in a way that’s unique and authentic to Memphis.’”

“Y’all make yourselves at home,” Karen Brownlee, the manager of Earnestine & Hazel’s, tells us as we stride into the cavernous storefront bar on South Main Street. Michael Jackson’s duet with Paul McCartney “The Girl Is Mine” coos from the sound system. “Pure comfort, right?” Samuelsson says when he sees the bar and the griddle on the left, with a short-order cook flipping burgers. “When a place is grimy, that’s when I get more comfortable.”

We order cold Budweiser in bottles and, having finally regained our appetites, the house’s revered specialty—in fact the only food it serves other than bags of Golden Flake potato chips—Soul Burgers. As we begin demolishing them, Samuelsson goes into full-on rave mode.

“The cook who made this,” he says, “he really cared. This is not just a tossed-off burger. The pickle, the cheese, the bun—this is like the perfect dive-bar burger.”

Photo: Squire Fox

Samuelsson and Nate Barnes of Earnestine & Hazel’s share a laugh.

The burgers are indeed remarkable, and after devouring several of them, our entourage trundles upstairs, which once housed a brothel. We head down a long hallway with peeling paint to a room at the front corner of the building, where Nate Barnes, in a homburg and vest, presides over a pocket bar, dark but for a strand of Christmas lights and the yellow glow from the sign hanging over the street. When Samuelsson lays eyes on Barnes, he pulls at the lapels of his own floral-print vest and proffers his hand. “Hey, I like your style!” he says.

“Where are you from?” Barnes asks.

“New York City,” Samuelsson says.

“I’ve been there,” Barnes says. “Well, White Plains.”

“That’s not the City, man. You have to come to Harlem!”

Samuelsson orders a round of whiskeys, and we settle in at a table next to the window as Jesse Smith fires up his saxophone and lights into “Soul Eyes,” the Mal Waldron tune John Coltrane made famous. When Samuelsson drops a folded-up bill in Smith’s tip cup, Smith says into the mike, “Thank you very much,” and—humble hustle dialed in—“The more you drink, the better I sound.”

The Soul Burgers have worked wonders, and as Smith’s sax takes a mournful turn, Samuelsson’s on his feet ready to go dancing. Lisle calls a group of friends to meet us at the Big S lounge, an old-school juke joint hard by the railroad tracks. We find it nearly deserted as we shamble in—only the owner, Sam Price, and a friend, Yolanda Grove, holding court at the bar. Grove tells us not to worry: “It’s about to get jumpin’. Just you watch!”

Price’s grandson, tending the bar, sets us up with some bottled beers and cups. After a half hour, the DJ arrives and starts spinning Curtis Mayfield and the Commodores. Lisle’s friends show up, and before long, Price’s regulars the Raynor sisters do too. Samuelsson starts dancing with Wendy, the one with the leopard-print skirt and the platinum bob. Within minutes, everyone’s on the dance floor. And just as Grove had promised, the joint is jumping.

Follow Chef Samuelsson's River City Tour

Where to Eat & Drink

Where to Eat & Drink (Cont.)

A & R Bar-B-Que

1802 Elvis Presley Boulevard

Memphis, TN 38106, United States

Ernestine and Hazel's

531 South Main Street

Memphis, TN 38103, United States

What to See & Do

National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel

450 Mulberry St.

Memphis, TN 38103