Sporting

Rick Bragg on Boys and Coon Dogs

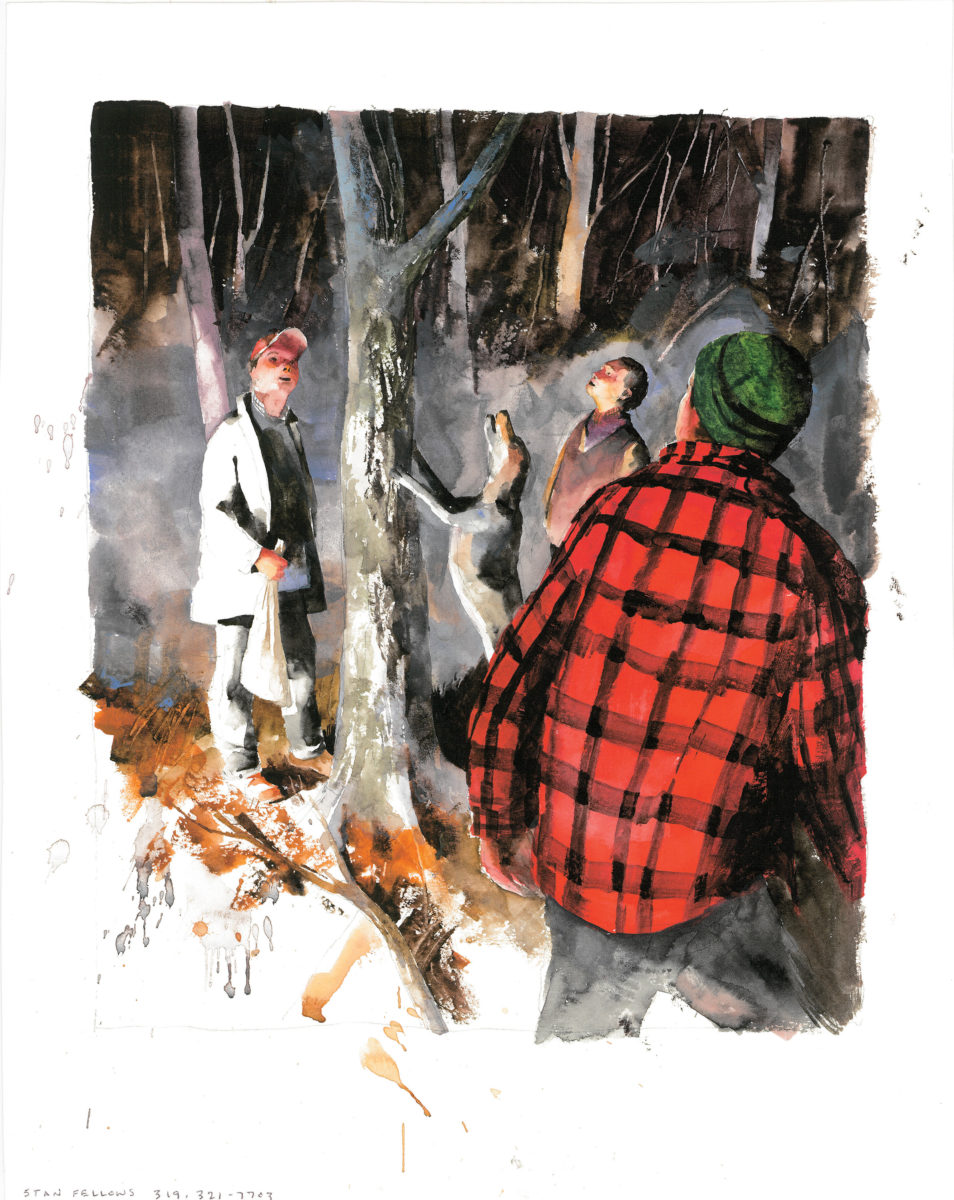

Illustration: Stan Fellows

I cannot remember everything, but I remember that stingy moon, remember a sliver of cold in a black sky, thin and useless. You might as well try to light your way with a piece of broken glass, for all the good it was. My flashlight, a relic from the Korean War, had died about eighteen seconds after full dark. The boys in front of me, friends, brothers, and cousins, mostly, were barely better off. They had to shake their hand-me-down batteries every few steps to coerce a last feeble glint of electricity, but I could have shaken mine like a Birmingham Hoochie Koo and still been walking in the dark. Only my brother Sam, who was born grown, who already had sideburns at age thirteen, had a good battery in his light. He was irritating that way. People said the day he was born he just dusted himself off in the hospital and walked home.

But, except for the threat of falling to our deaths down some crevasse, I guess we did not really need light. Our direction was determined not by what we could see but by what we could hear. We followed the sound across that frozen ground, followed a thing faint, constant, lovely, as we trudged single file across the haunted ridges and deep into the black hollows, the mist shining silver where that one good flashlight bored through the dark.

I can still hear it, after all these years. The poet in me—well, the never-was poet in me—would like to call it music, but it was prettier than that, prettier than I can say. It would have been nice to sit on a porch and hear it, but the other boys looked at me funny when I suggested that. Only the boys afraid of the dark, or the cold, or monsters, stayed home. I went, this one time, to show I was not one of them.

I was the youngest, and so the last in line. As we made our way diagonally up a ridge, rocks turning our ankles beneath the slick carpet of leaves, I felt myself begin to slide sickeningly straight down the mountain, straight toward what I knew to be a bone-breaking deadfall. I caught myself on a gummy pine sapling, breathed a minute, and started up again, even farther behind. No one had even turned around, and the romantic in me, the one who read about lost souls on desert islands, wondered how long I would have lain there, broken and forgotten. My brothers said I thought like that because I read too many books.

But falling was not romantic on the mountain. Falling was what you did up here. You walked; you fell. You chewed some Brown’s Mule, or some Beech-Nut, if your stomach could handle it. I did not chew, so mostly I just walked and fell.

What a dumbass I was, I thought, as I slid again and lost thirty yards of the uphill ground I had gained. A smart boy would have chased some brighter light, somewhere, because the light was where the girls lived. A smart boy would have been in town, leaning on the hood of a car at the Rocket Drive Inn with a Cherry Coke in one hand and a beautiful woman in the other. Or, at least, that was how I figured it should be. I was not yet ten years old, and a beautiful woman would have sent me into a convulsion.

No, we went the other way, away from perfume and soft shoulders, gouging deeper and deeper into the dark, into the foothills of the Appalachians along the Alabama-Georgia line. It was November, maybe even as late as December, 1969, but it could have been any night when boredom was stronger than common sense, after the cold sent the snakes down into the earth, and walking out into nothing was as much adventure as we could divine.

My big brother, Sam, was only three years older than me, but he drove a Willys Jeep he had hacked out of a rust pile and made to live again by soaking its bones in buckets of dirty gasoline. And so, he got to walk in front. He had an ax in a tow sack, but no gun. This was as far from a gentleman’s hunt as I guess a fellow could get.

We were all the same, us boys, on the outside. We did not own big parkas or camouflage anything, because while we still had real winter back then, it was too short in which to invest much wealth. We wore flannel shirts and thermal undershirts and something called a car coat, a thin and useless thing that, as near as I could tell, was made out of polyester, cat hair, and itch. Walmart would, one day, sell a trillion of them. We got a new one every other year; that, and a gross of underwear.

The smart ones in the group wore two pairs of pants, even three, because the briars ripped at our legs with every step. Sometime, back in the times of our grandfathers, these mountains had been old-growth hardwoods and towering pines, but none of us could remember a time when the South looked like that. Old men talked of an age when the great trees towered into the clouds and the forest floor was dark and smooth and clean, but these mountains had been clear-cut generations before, creating a tangled mess of skinny trees fighting for the light, with undergrowth and saw briars strung between them like razor wire.

It was a time before hunting was a fashion. We hunted in our work boots, laced up around two pairs of socks—three, if you were growing into them. The ones who had gloves wore them and the ones who didn’t walked through the woods with a pair of tube socks over our hands. I guess an outsider would have laughed at us, but outsiders did not get to go.

So armored, spitting , and breathing hard, we attacked the mountain. And no one said a word. I tried to whine, once, and ducked just in time to avoid being slapped back down the mountain.

“Hush,” my brother hissed, then, gentler: “Listen.”

The baying was so thin it vanished in the wind in the trees.

But he could hear it plain.

“Joe,” he said.

***

We often got things, back then, no one else wanted. We were the poorest relations and naturally became the repository for things cracked, busted, rusted, or slightly burned. Kinfolks and other well-meaning people brought us these things with a straight face, but we knew. The dump charged between three and five dollars a load, while we took their castoffs for free, took their refrigerators that did not cool, and fans that did not spin, and big, heavy televisions stuck permanently on a horizontal roll. “You can fix it,” they always said, and drove away. At one point, my grandmother Ava had three radios on her dresser that were as mute as a stone. People even brought us tires worn completely through. “You can get them recapped,” they said. Now how in the hell do you do that, unless your last name is Goodyear?

That is how we got Joe.

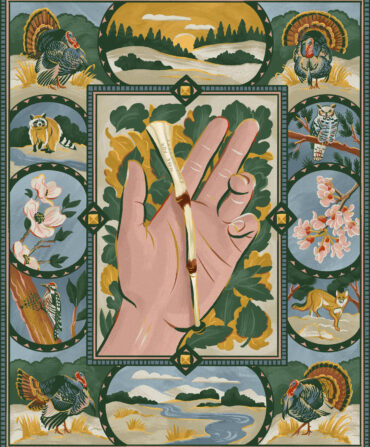

Joe was a coon dog, a fierce mixed-breed dog, a mass of quivering muscle and intelligence. You could see the black and tan in him, and bluetick, and even some red feist, but mostly he seemed composed of thin white lines where his body had been ripped and torn, as if instead of breeding those bloodlines into him some Doctor Frankenstein had just sewn him together from spare parts. He had a savaged snout and no ears, none. Coons had chewed them off at the skull.

We got him not because he was wounded or finished, but because he would not stay in a pen. He belonged to a tough old pulpwooder named Hoyt Cochran, who penned him with a gyp named Bell. But Joe was a climber, and so, when no one was looking, he would scale the chain link or dog wire like a monkey and go hunt free. He did not run trash, and he was fearless, and he would hold a tree for five hours. “Hold a tree all night,” my brother said. But a dog that cannot be kept is a worrisome thing, so Sam bought Joe cheap, probably saving him from a bullet.

He drove a steel rod in the dirt of the backyard and fixed to that several feet of heavy chain. Joe lived most of his long life that way, staked down between his water bucket, food bowl—really an upside-down hubcap—and his doghouse, a plywood shell covered over with shingles and filled with fresh hay.

I would watch him there many days, my heart breaking a little, be-cause nothing should live like that. Every now and then the wind would carry a scent to him there and he would drag his chain in the direction of that smell and pull it tight, his ruined nose twitching, and bay.

It came to me eventually that his time on the chain was not living, and the only time he was really alive was on the mountain. There, he was something different. “He beat a lot of dogs, a lot of expensive, pure-breed dogs,” Sam said, years later. To him, Joe was just one more discarded thing he was able to get some good out of, his way of saying to the discarders, yeah, the joke’s on you.

Joe knew it, too, knew that he was something more. If he treed a coon with a pack of lesser dogs, or just one noisy dog who barked if he treed a coon or barked if he scratched himself, he would set himself apart, and fix his head in the direction of the coon and hold it there, as if to say to the humans, If you were gonna bring along this white trash, what did you need me for?

“He didn’t like an ill dog,” Sam said. “He meant for the others to behave.”

He hunted him with a pure-breed black and tan named Blackie, a gift from an uncle. Blackie had a lovely voice but was prone to get lost and wander for days.

But together, off in the distance, they made that beautiful sound.

Coon dogs have one bark when they strike a trail, an excited, insistent one, and another, steadier, melodic, as they trail, and a third, urgent, excited, when they tree. But it was the trail bark that was most lovely.

“Joe had a kind of sharp ‘yerp’ sound, and Blackie had more of a ‘yowl,’ and when they were on that trail that sound would get to rolling, kinda, in the distance, and that was what was so pretty,” my brother said.

Illustration: Stan Fellows

***

Yerp!

Yowl!

Yerp!

Yowl!

And the boys in the cold and the dark forgot about falling off the mountain and slid and scrambled in the direction of that sound, faster and faster. It was the pure excitement of it that hurried them, not the chance that Joe would not stay treed. Sam knew that when he got there, there would be a coon either in the tree or dead on the ground, because if Joe caught one in the open, it was done. “He learned to kill them without getting hurt real bad, but not in time to save his ears.”

This night, we were still what seemed a mile away when we heard that change—heard the baying ratchet itself up—and knew that the dogs were treed.

“Talk to ’im, son,” my brother hollered, and the other little boys whooped, and I swear one or two of them jumped for joy. To say we didn’t get out much does not nearly cover it.

We got there in time to see Joe running a wide circle around the tree, once, twice. That way he made sure that the coon had not outsmarted him and slipped away. Then he put his front paws on the trunk, and sang to us. Our one good light played up into the branches of a pine, and there he was, a big boar coon. I know that a big boar was more than enough for most dogs, all teeth and razor blades. But he did not look big or dangerous. He just looked scared, behind his black mask, a thing I knew to be deceptive. Sam climbed the tree and, carefully, with a small ax, knocked the coon to the ground, and the dogs closed in. That might not be the way others did it, the purists of this sport, but it was the way a troop of bloodthirsty redneck boys did it in the winter of 1969. I do not remember a terrible fight, because Joe was such an assassin and was on his throat in an instant, but I remember an odd quiet when it was done, and boys, looking like little boys again, milling around, not sure what to do with their hands. We put the limp coon in the tow sack. There was a man in Jacksonville who paid cash money for it, not for the skin but the meat.

My brother hunted another forty years, and still does, when his wore-out body will allow. He grew gentler—not a lot, but some—and sometimes just hunted to hear that sound, and dragged his dogs off the tree and went home once he knew the pretty part of it was done. He saw the sport change, and changed with it. He hunted on into his fifties, on into an age of tracking devices and shock collars. He carried a GPS. He asked me once to put the shock collar on so he could test it, but I have gotten some smarter since 1969.

But my time in the mountains, listening to the dogs, ended when I was a boy. When I think of it, which I often do, I am always ten years old, waddling across that mountain in so many pants my legs won’t bend at the knee, knowing that if I fell I would never get up again.

Joe lived to be more than fifteen years old. “I finally just turned him loose,” said my brother. “His teeth were wore down to nothing. But you know, I’d come home from work and he’d be gone, and I’d hear him off in the distance, and I’d have to go and get him off a tree, somewhere behind the house.” It may be that there was a coon up there, or, near the end, it may be that he just thought there was. I guess there is no reason to think he would be any different from people, in that way.

Every now and then my big brother will ask me if I want to go for one last walk up the mountain, behind a new dog, but I just say, no, I’ll listen from here. From the porch of my mother’s house you can sometimes hear that sound, faintly, drifting down through the trees, and I shift my weight on the boards of the porch, and think how fine it is that an old man does not have to prove he is any kind of man, anymore.