Arts & Culture

The Bold and Generous Spirit of Lee Smith

No one has tapped into Southern truths quite like the Virginia-raised author, whose fifteen novels span Appalachia to the Florida Keys. Just ask the legion of writers who praise Smith for guiding their own stories

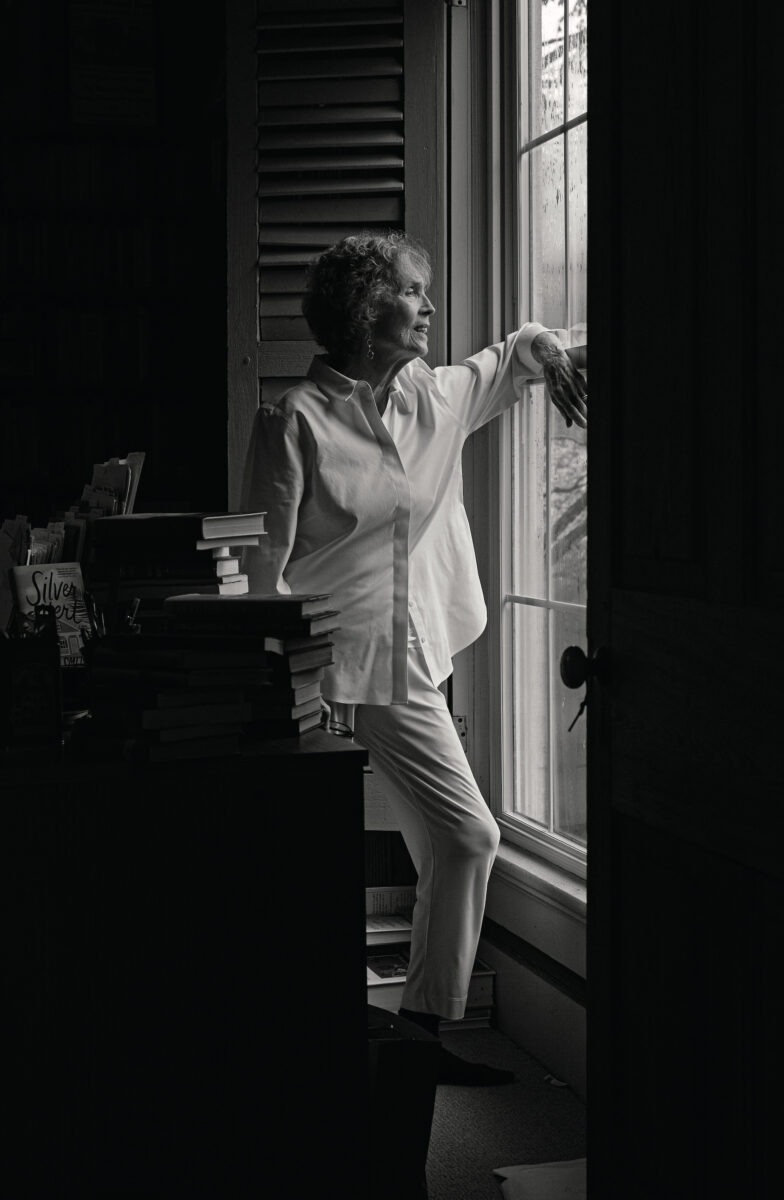

Photo: Gately Williams

Lee Smith in her sunny home office in Hillsborough, North Carolina.

Lee Smith glides through the pouring rain, her distinctive laugh curling out behind her. Once she reaches the back stoop of her antebellum house in downtown Hillsborough, North Carolina, she shakes a spray of droplets from her hair and wipes water from her face. “Oh, Lord, that was magic!” she will recall later, even though now she is drenched by the cold cloudburst that is still pummeling the ground. I’ve long noticed how she seems to find the positive in every situation. I see joy in her vivid blue eyes. There’s a hint of mischief in them, and in that smile that overtakes her whole face. She’s known for her kindness, but also for her tenacity. She punctuates the occasional curse word she drops with a gleeful brow lift that widens her eyes and acknowledges her naughtiness. She’s petite and birdlike in her movements but large in presence; when she enters a room, everyone knows it.

In the world of Southern literature, Lee Smith’s big personality and her melodious laugh are the stuff of legend. Smith, who grew up in the little Appalachian town of Grundy, Virginia, is one of the most beloved and acclaimed writers of her time. Along with pioneers such as Bobbie Ann Mason, Lisa Alther, and Alice Walker, she was part of the “New South” literary movement of the 1980s that changed American literature, depicting a South that was more Hardee’s and Kmart than it was magnolias and general stores, more women’s issues and civil rights than good old boys and cotillions.

Smith published her first novel, The Last Day the Dogbushes Bloomed, in 1968, only a year after she graduated from Hollins College (now University) in Virginia. She studied there alongside another future legend, Annie Dillard, with whom she once served as a go-go dancer for an all-girl rock band called the Virginia Woolfs. Since then, Smith has raised two children, taught at high schools and universities, and published fourteen more novels, four short-story collections, and a memoir. Along the way she’s collected two O. Henry Awards, the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award for Fiction, and the Southern Book Critics Circle Award, and cracked the bestseller lists. This past spring, before her fifteenth novel, Silver Alert, came out, her friend Dolly Parton read it and wrote in a letter to her: “It’s very different and it’s very special and it’s very good! I loved it.”

Smith has also mentored, guided, and believed in many of the South’s next generation of writers, including me.

“I’ve been thinking about my own age,” Smith says as she puts out breakfast—sweet rolls, quiche, and strong coffee—after drying off. She will turn seventy-nine in November, and she recently faced a string of age-appropriate ailments that have made her think more about aging than ever before. “You know, no matter how healthy you are, health does become something you have to come to terms with. That’s one thing I’ve always done with my writing, I think—used it as a way to come to terms with issues that I may be having myself.”

Silver Alert came into being about six years ago during a Florida Keys jaunt along Route 1 with her husband, the writer Hal Crowther. Driving home, they encountered a highway sign proclaiming a Silver Alert—a public notification about a missing senior citizen. “It had the make and model of the car. It gave the license number, and it had a number to call,” Smith says, drawing her hand across the air to conjure the image. As they drove, the couple started making up the story, rooting for an imaginary old man to make his escape. “We’re just saying, ‘You go!’ and by now…we’ve made up that he’s got a passenger with him. The story just sort of started happening in my head.”

Photo: Gately Williams

Smith’s historic home in downtown Hillsborough.

Silver Alert centers on Herb, an eighty-three-year-old man who escapes Key West for a joyride after discovering the car keys his children had taken from him. “I love him because he’s not going quietly or gracefully into that good night,” Smith says. “He is kicking and screaming and acting awful and acting out…I think most of us are too polite. We think old people should just calm down and go sit in the corner and he’s just, ‘What the hell?’”

Herb’s passenger, Dee Dee, a mysterious manicurist from Appalachia, is on the run from true evil. Smith studied manicure techniques to accurately portray Dee Dee’s work. “I have a real good friend who is a young manicurist,” Smith says. “She taught me a lot…I learned how to do it. It’s an art. I mean, it’s a real art.” The story unfolds from their two wildly different viewpoints: Herb’s sections examine aging, while the chapters focusing on Dee Dee tackle sex trafficking, both issues that have become close to Smith’s heart.

Smith first learned about the perils of sex trafficking through Thistle Farms in Nashville, which provides support and housing for female survivors of trafficking, prostitution, and addiction. She performed alongside friends Matraca Berg, Marshall Chapman, and Jill McCorkle in their music-and-monologues show called Good Ol’ Girls as a fundraiser there, and she’s also worked with similar groups in North Carolina and Maine, where she and Crowther spend their summers.

Silver Alert reads a bit like an unintentional companion piece to Smith’s 2020 novella Blue Marlin, which was inspired by her family’s real-life stay in Key West when she was a child. Both her parents suffered from depression, and a psychiatrist suggested they go to the island for “a geographical cure for their marriage,” she says. They stayed three months, and Smith went to school there. “Cuban girls pierced my ears,” she remembers. “In church, they thought it was a sin!” In both books, young Appalachian women find healing in Key West. “I think it’s because it’s divorced from the mainland,” she explains. “It’s America, but it’s not. It’s just a place where you can be who you really are—or who you might really want to be that you might not even know until you get there.” She leans forward over the kitchen table, hands floating before her. “And it just has always had that effect on me. The quality of the light, the immense sky…So here I am, back on Route 1 again.”

Smith was raised in Grundy, a coal-mining mountain town in Southwest Virginia, a place very different from Key West or North Carolina’s Research Triangle, where she has lived most of her life. But she says it’s no surprise that an Appalachian character has shown up in the new novel.

“Seems like whatever I’m writing, somebody will be Appalachian,” she says as she climbs the stairs to her office, where shelves overflow with books and framed pictures of her children, grandchildren, and many writing friends. She turns reverent, struck by another thought about back home. “When you’re from Appalachia, it never leaves you. It just imprints real hard. And I mean, I’m glad it does. But it really does.”

Photo: Gately Williams

She often writes and revises her work by hand.

Although she moved away from the region about sixty years ago, she still pines for it. In her 2016 memoir, Dimestore, she writes about her complex love for Grundy; like many rural Americans, she couldn’t wait to leave but then found the place never left her. In one particularly moving scene, she relates a memory from when she was a teenager at a drive-in movie where the Stanley Brothers—before they were famous—played a set during intermission atop the concession stand roof:

Old people were clogging on the patch of concrete in front of the window where you bought your Cokes and popcorn; little kids were swinging on the iron-pipe swing set. Whole families ate fried chicken and deviled eggs they’d brought from home, sitting on quilts on the grass. My boyfriend reached over and squeezed my sweaty hand. The Stanley Brothers’ nasal voices rose higher than the gathering mist, higher than the lightning bugs that rose from the trees along the river as night came on.

In one short passage, she manages to conjure Appalachia’s best parts: the community feeling, the music, the safety of familiarity, good food, and the markers of place—mist, lightning bugs, the river—we can never forget. The scene is also quintessential Lee Smith in that it is simultaneously funny, moving, and a remarkable conjuring of place and time.

“I’m homesick all the time,” she says. “I just get so excited…when I get to go to Grundy.” Last year I was with her on a return visit for the unveiling of a huge new sign declaring it as the HOMETOWN OF AUTHOR LEE SMITH. The local library hosted a two-day celebration featuring a church homecoming–style supper with casseroles, ham, chicken and dumplings, various salads, and a dessert table overflowing with homemade cakes and pies at the First Presbyterian Church fellowship hall; a lengthy luncheon that ended with tributes from writers including Carter Sickels, Heather Frese, and me; as well as a cocktail party hosted by a childhood friend where stories of Smith’s teenage adventures had us laughing far into the night.

She’s kept Appalachia alive in her large home in the writers’ enclave of Hillsborough, too. “Practically everything in this house came from my parents’ house in Grundy,” Smith says of the antique furniture that surrounds her. “I always use one of Mama’s mixing bowls whenever I’m making biscuits or bread or a cake. I still have her recipe box right here.” There are also hand-stitched quilts, paintings of fiddlers, and stacks of CDs in the kitchen, mostly featuring her homeland’s music.

Matraca Berg, who has written country music classics such as “Strawberry Wine” and “You and Tequila,” says Smith’s 1988 novel Fair and Tender Ladies, set in the Blue Ridge Mountains, was a life changer for her. “I knew [the narrator] Ivy’s voice right away,” she told me recently. “So much like my granny who was born deep in the mountains with just elementary education. It startled and excited me because I thought great Southern literature was mainly set in the Deep South. It was a revelation. Lee has such a heartbreakingly beautiful, lyrical quality with her words. I read everything of hers.”

Tayari Jones, the author of such best-selling books as An American Marriage whose work Smith championed early on, says that one of Smith’s greatest strengths is that she is “an unapologetically regional writer. This is not to say that her work is only of interest to those who hail from Appalachia. I mean this to say that she represents and embodies her home in her art. She presents the folks around whom she grew up without sentimentality and without explanation to the rest of the world.” Jones compares Smith’s ear for the rhythms of speech to Zora Neale Hurston’s. “This magic comes about when three rare circumstances occur simultaneously—an artist possessing a staggering talent also demonstrates incredible discipline and rigor while honoring, loving, and respecting the culture that shaped her.”

Smith’s insistence on keeping her focus regional may have kept her from becoming a larger name internationally, but she says she never worried about that: “I’ve never paid very much attention to my career. I’ve just been writing.”

When I was twenty-four, Smith came to do a reading at a library near my hometown of Corbin, Kentucky. I hovered at the end of her signing line to tell her how her work had transformed me as a writer and a person, mainly because she was the first writer to make me feel like I had seen my own people in literature. Serendipitously, she had recently read my first published short story and remembered my name. This was enough to make her insist that I attend the Appalachian Writers’ Workshop at Hindman Settlement School in Knott County, Kentucky, where she often taught. The school is a literary and literacy center for Appalachia, offering creative writing classes as well as adult education, GED services, and one of the most respected dyslexia programs in the country. I was working as a part-time mail carrier then, and I scraped together enough money to pay my tuition, but I didn’t have enough for room and board. The director allowed me to set up a tent on the creek bank behind the school. Perhaps seeing my dedication to learning more about the craft caused Smith to pull me closer beneath her wing. Like the best teachers, she saw something in me that I couldn’t yet see in myself. She offered to read my novel when I finished it.

That entire week felt like a dream to me, getting to sit on a porch and jaw with my literary hero not only about writing, but also about the similarities in how we grew up, the music we loved, our affection for dogs. I went home so energized that I lit into that first novel in a whole new way. Smith read it immediately and wrote me back a long letter full of praise, diplomatic criticism, and advice for making it better. Working with her and the other writers she introduced me to shaped my whole career, and she has never stopped encouraging and nurturing me, particularly in my most difficult times personally and professionally. I think of her as my literary mother and a constant comfort.

When I spoke to other writers about her, I found I was not alone in feeling this way. “I’m grateful to Lee for so many things: her craft, her kindness, her fabulous laugh,” says the recent Pulitzer Prize winner Barbara Kingsolver. “For her confidence, writing Appalachian stories that showed me the way into my own place and people, when I was a young writer struggling to find self-respect. And then, as soon as I’d entered the canon of Appalachian writers, she generously praised me as a peer.”

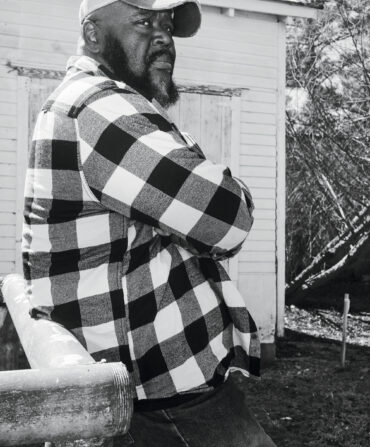

Photo: Gately Williams

The author and Smith in front of Smith’s carriage barn, which dates to the nineteenth century.

Wiley Cash, a three-time Southern Book Prize winner, says Smith is “the Dolly Parton of American literature. Her kindness, wit, and warmth make you want to be near her, but it all belies an intense intelligence and devotion to her craft.”

Her two most recent editors say one of her greatest strengths is her determination to keep growing as a writer. “She was always open to suggestions, always willing to reconsider, and always ready with better remedies than what I suggested,” says storied editor Shannon Ravenel, who worked with Smith on bestsellers such as The Last Girls and The Christmas Letters. Smith’s current editor, Kathy Pories at Algonquin, agrees. “She is game to dive in. When we were working on Silver Alert, we sat on her porch and as I talked, she diligently took notes, filling up pages of her legal pad, looking up often to say, ‘Oh yes, I like that idea.’ If I had to describe her in one word, or okay, let’s make it three, I would say ‘generosity of spirit.’”

Upon Silver Alert’s release, Smith went on a short book tour with Daniel Wallace, the author of widely read books such as Big Fish who had just released his memoir, This Isn’t Going to End Well. Wallace was a student of Smith’s at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and remembers her class as formative, fun, and energetic. Smith recalls that the first day of class he showed up wearing “red tennis shoes, his mother’s full-length mink coat, and some kind of hat.” She throws her head back and laughs.

Wallace later tells me that when his first novel was being considered for publication, Smith wrote a letter to a publisher to explain why they should buy it, and they did. “She’s the most generous writer on the planet,” Wallace says. He’s amazed to have been able to tour with her. “There are some dreams you don’t dream, because they are outlandish even for a dream: Writer and mentor sharing a happy ending and happier because it’s not an ending at all.”

Smith waves off any suggestion that her support of other writers has been unusual. “I feel like it’s a responsibility to help other people,” she says. “I love to teach. You can help people, you can inspire them in certain ways, or you can help them improve what it is that they are writing. The teaching has been a great privilege for me.” When I ask her how she can be repaid, she shrugs. “Just pass it on.”

The rain has stopped now, and Smith is leaning in her long office window, bathed in the kind of golden light that only exists after a rainstorm. She looks down on her wild front yard, which she has not allowed to be mown because it is covered in buttercups. She says that when they all bloom out, she will invite the whole neighborhood over for cocktails so they can enjoy them, too. “We do it every year and have the best time.”

Over the years Smith has often talked about having been “so wild” that her parents sent her off to boarding school. She has told the story many times of getting kicked out of the international travel program in college for “staying out all night in Paris.” I ask her if she still feels wild, and mischief sparks in her eyes as she folds her hands before her. “Yeah.” A mixture of slight embarrassment and happiness is alive on her face. “I do.” Her eyes cast down onto the backs of her hands. “I think now my characters act that out. That’s the great privilege of being a writer. When you get too old to do it yourself, your characters can do it.”

A couple of hours after I leave for home, Smith calls me just as I reach the first rises of the Appalachian Mountains. She wants to make sure I’m driving safely as a ferocious storm lurches across the region. After we hang up, I fish around in the bag of food she packed for my ride: a can of Virginia peanuts, potato chips, a sleeve of saltines, a can of Vienna sausages, and dark chocolate truffles. I keep thinking about how good she has always been to me, and how she feels fortunate both to be a writer and to be part of other writers’ lives. I return to the remarkable characters she has created—Ivy Rowe, Almarine Cantrell, Kate Malone, Crystal Spangler, Florida Grace Shepherd, Jenny Dale—and the scenes from her books that remain so clear in my mind, years after I read them.

I can see her in her office, the light streaming down as she goes right back to writing, just as she has always done. She’s working on a novella right now, as well as short stories. One piece, “The Cutter,” centers on an Appalachian woman finding her own power for the first time. Smith is especially thankful these days that stories and characters have come to her so vividly for so long. “It was always…what I did to make sense of my life,” she says. “It has kept life very interesting, because I think if you’re listening out for stories, you will hear them. Stories just show up for me.”