Arts & Culture

The Katrina Class

A decade after Hurricane Katrina, we track the storm’s impact on some of its youngest victims

Photo: Darren Braun

August 2005 began with promise for the third graders in Room 10 at the Phillis Wheatley Elementary School in New Orleans’ Tremé neighborhood. Then Hurricane Katrina came, scattering the students throughout the South. Ten years later, what happened to those thirty-four children—and the countless others like them—is a story we’re only just beginning to piece together

Hurricane Katrina started out pretty fun for Jonathan Cotton. When you’re in third grade, school’s been canceled, and the street is filled with water, the day holds nothing but promise.

The power in Jonathan’s Sixth Ward apartment had gone out early on that August Monday a decade ago, when the worst of the hurricane swept over New Orleans. He lived on the edge of the Tremé neighborhood, in the Lafitte housing projects, with his mom, Gail, and his little sister, Niairi. The sturdy brick buildings, a short walk from the French Quarter, dated back to 1941. Some of the poorest people in the city lived there, but even with more than eight hundred units and a steady market for dime bags of dope, they were nicer than most housing projects, dressed up with clay tile roofs and wrought-iron railings. It was the kind of place where residents looked out for neighbors and grandmothers.

The day before, mayor Ray Nagin had ordered everyone to leave. Some of Jonathan’s neighbors did, but most had no intention of going anywhere. Instead, they laid in groceries and charcoal for grills to keep the food coming when the power went out. Some gathered friends and relatives from less safe buildings. Some threw hurricane parties. It was what people in the Lafitte always did. Besides, many had never even been out of New Orleans. Where else were they going to go?

Photo: Rush Jagoe

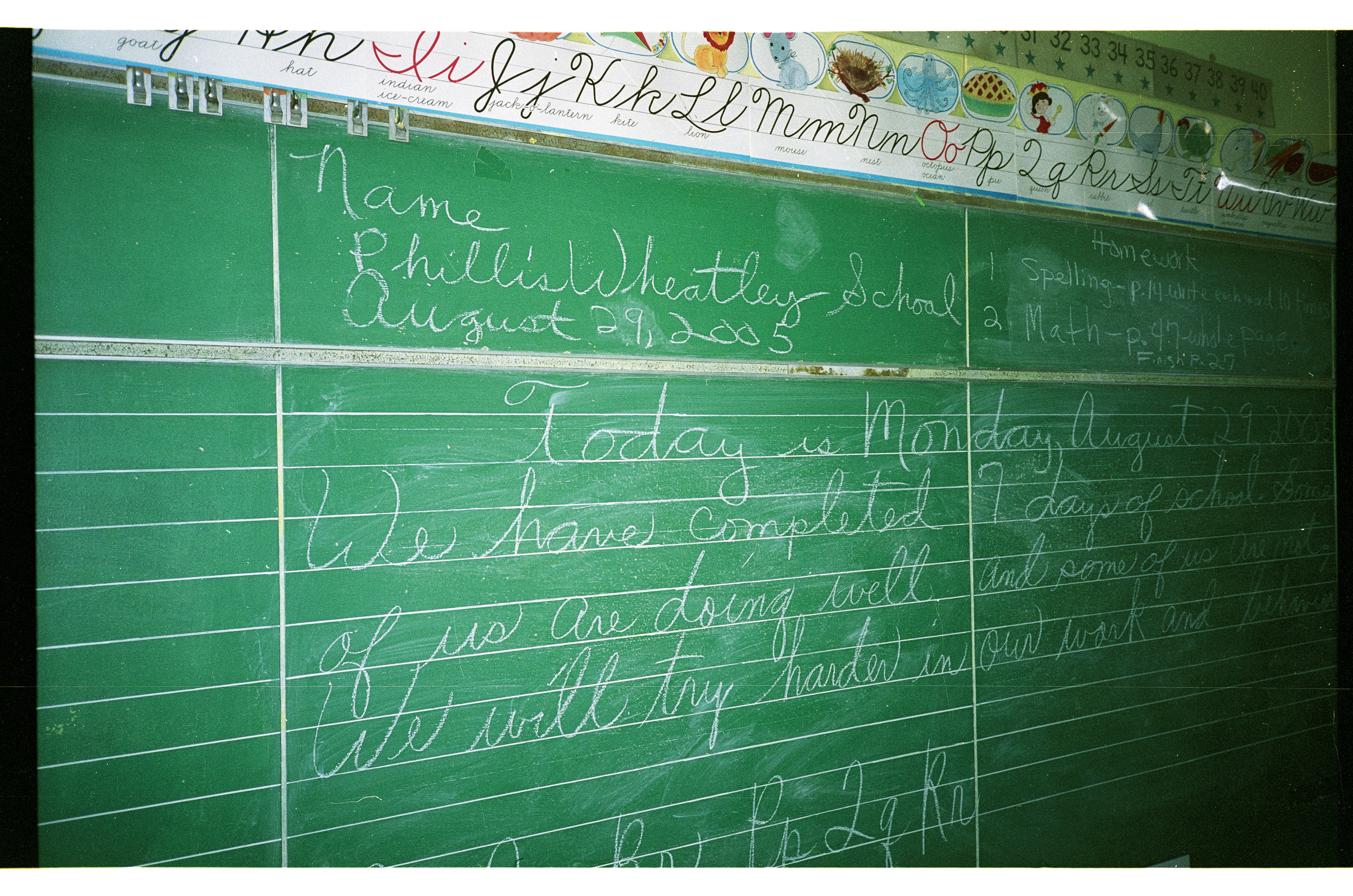

The chalkboard in room 10.

Though parts of the city had flooded early, Lafitte residents made it through the actual storm just fine. By Monday night they were picking up tree limbs and sweeping sidewalks. But when they woke up Tuesday morning, the water was rising. Soon, streets throughout the Tremé were flooded. The federal levee system that was supposed to protect the city couldn’t hold the surge of water Katrina brought with it. Some neighborhoods took on water past the rooflines, with houses shoved aside as if a child had thrown a tantrum in his playroom. Nearly half of the 986 Louisianans who lost their lives as a result of the storm drowned.

Here, in front of Jonathan’s house, the water might have only hit a man’s chest. Still, it was everywhere, cutting them off like castaways. Gail Cotton could still cook pan spaghetti on the gas stove, and she had stockpiled Vienna sausages and other snacks to keep everyone who had gathered fed. But the panic was rising with the water.

By Wednesday night, when it was clear they would be penned in for yet another day, a few adults made their way across the street and broke into a corner store, wading back with batteries and food and beer. Someone handed Jonathan a big pack of Hubba Bubba, which he tossed back and forth with Hakeem Carter, his best friend, whose porch was next to his but up on the second story. Hakeem had been hit by a car earlier in his young life, and it had changed him a little. He liked to play as hard as Jonathan did, but he was smaller and less rambunctious. And he couldn’t swim.

“I was worried for him with that water,” Jonathan told me this spring, over a cheeseburger at an Applebee’s in an Atlanta suburb. “He had to get himself carried on his uncle’s back when we were getting out. I thought he had died, so I was just begging my mom to take me back to find him.”

When we shared dinner, Jonathan had been away from New Orleans for seven years. His mother, who lost her job as a city bus driver after Katrina, just couldn’t make it work there anymore. That day he and Hakeem shared gum in August would be the last time they would talk to each other until almost ten years later, when I managed to track down Jonathan and hand him Hakeem’s cell number.

Photo: Rush Jagoe

The Graduate

Now living near Atlanta, Jonathan Cotton completed high school in May.

The two boys have haunted the documentary filmmaker Joe York since 2007, when he walked into a classroom and found their names on a list of thirty-four children who had just started the third grade in Room 10 of the Phillis Wheatley Elementary School the month Katrina hit. York was in the neighborhood filming a documentary about the effort to rebuild Willie Mae’s Scotch House, a little bar and restaurant beloved for its spicy-batter-dipped fried chicken that had been ruined by floodwater during the storm. He had gone into the abandoned school in search of a quiet place to work.

Like an explorer who stumbled onto Pompeii, York found a room frozen in time. Everything down to the chalk was just as it had been when the teacher, Linda St. Martin-Scott, had prepared it for a Monday of instruction that never came. The room had the specific stifling smell of swampy decay, and paint was coming off the walls in sheets. The hands on the clock had stopped just after 5:00, most likely the moment in the morning two years earlier when the storm cut off electricity to the neighborhood.

The chairs were so beat up they seemed better suited for the dump, but you could tell the well-organized classroom had been run by someone who cared. There was a pretty orange paperweight on the desk and math games stacked on a shelf—all the handiwork of St. Martin-Scott, who had taught at the school since the 1970s.

Still on the chalkboard were a few motivating sentences she had written before leaving school that Friday for the students to see when they returned after the weekend: “Today is August 29, 2005. We have completed 7 days of school. Some of us are doing well and some of us are not. We will try harder in our work and behavior.”

“I didn’t think it was going to be a goodbye note,” she said over lunch earlier this year. “We were just a happy family there. They depended on us to nurture them. Our motto was ‘From little acorns great oaks grow.’”

When York left Room 10, he slipped a copy of the class roster into his pocket. Nearly ten years after the storm, he asked me to help him find those kids. They had been scattered like confetti from Houston to Atlanta to Natchitoches, about 250 miles northwest of New Orleans.

Photo: Rush Jagoe

Roll Call

Tiaona Torregano, Hakeem Carter, and their former teacher Linda St. Martin-Scott.

At first, we simply wanted to see what happened to them. But it soon became clear that we were piecing together a narrative that told the story of the nation’s most dramatic and expensive storm-related disaster through the eyes of children who were eight or nine. These were the stories of tiny heroes who, now ten years later, had suffered through not only those awful first days after Katrina but indeed the years of emotional, physical, and political tangles that followed. And they’re not alone. They are members of a large class of children who endured a common horror, the effects of which have only recently come into focus.

As I dug deeper into what happened to the students in Room 10, I found a small, dedicated group of researchers who have made it their life’s work to track the effects Katrina had on some of the 100,000 children who left the Gulf Coast after the storm. The children’s stories, measured in cases of post-traumatic stress and heartbreaking reports from schools and parents and police, are just beginning to coalesce into what the researchers hope will become a new set of federal policies designed to mitigate the impact of disasters on children and the long-term displacement that might follow.

“Now at least we have some evidence to move into policy,” says Lori Peek, a sociologist at the Center for Disaster and Risk Analysis at Colorado State University who, along with Alice Fothergill, has studied hundreds of children who survived Katrina. “In other disasters we might think, what does a kid need a week or a month out? With Katrina, we needed to think, what do they need a year out or even ten years out?”

Their book, Children of Katrina, will be published this September. “We can’t just say these children’s lives were impacted because they were poor and African American,” Peek says. “Katrina did something to these children, and it did something severe and profound and long lasting.”

To understand what Katrina might have done to the kids from Room 10, it helps to understand the developmental stages of a child who is eight or nine years old, when the foundations for logical thinking, literacy, and comprehension are being laid. The children of Room 10 could understand what was going on around them but hadn’t yet developed skills to cope with nights inside the dank corridors of a scream-filled Superdome, watching soldiers pull guns on parents who were waiting to be evacuated on buses or planes, or months of moving among shelters and relatives’ couches and hotel rooms. Most never saw their homes, or some friends or family members, again.

It is not an understatement to say that for a lot of the third graders at Phillis Wheatley, most of whom struggled with poverty, life was already challenging enough. “We still don’t know what that trauma on top of trauma that they might have already experienced has done to these kids,” says LaRita Francois Flotte, who runs the Take the Lead Foundation, a grassroots organization that provides training to young people who would have been in elementary school when Katrina hit. It is located in the heart of the Tremé and is one of a handful of groups trying to fill the overwhelming need for job training and GED programs in a state that has the highest rate of young people who are not in school or working—a statistic, researchers say, that is directly related to the storm.

There is no linear, methodical way to find children who were shot out of their neighborhoods in such terrifying circumstances. It’s surprising, given the proliferation of social media. But these are not families whose lives rise and fall on the latest Facebook post. Like many students in New Orleans schools when the storm hit, their records were all but erased. Some had come back and were finishing high school, but many did not.

The public housing apartments where Hakeem and Jonathan had grown up had been demolished by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. In their place stand new wooden buildings painted in pastels, which rent to families of all income levels. We couldn’t find one family from Room 10 who had moved into the new housing project.

The projects, which once covered twenty-seven acres, aren’t even finished. In fact, this slice of the Tremé—part of the oldest black neighborhood in the country and the birthplace of jazz—still feels like it’s rebuilding. People from the projects and indeed much of the Sixth Ward had always been tight, and before the storm you could usually find an auntie or an old boyfriend who could help you find whomever you were looking for. But that network had been blown up. In the end, we could locate only ten students.

One of the first was Akia Bennett, whose father, Anthony Bennett, is the leader and drummer of the Original Royal Players brass band, a New Orleans institution revered for its traditional marching style. Akia has struggled since Katrina. She is eighteen and hasn’t set foot inside a classroom for a couple of years, although she wants to get her GED. In the meantime, she works at McDonald’s and as a shot girl at a nightclub called the Beach on Bourbon Street.

It would be hard to find someone who is more loyal to the four-block slice of the Tremé she grew up in. She insists on a tour, showing off the Treme Recreation Community Center, where she spent her summers and learned to swim, and the site of the old corner store where she used to swipe candy.

Akia didn’t experience the dark trauma of days inside the Superdome or panicked nights at the convention center, like some of her classmates. Before the storm came, she was packed into a car with nine other people and as much stuff as her family could fit. They headed to Houston and stayed in a shelter for what they thought would be a few days. She was in that city for a year. Akia can’t quite recall, but she doesn’t think she went back to school at all in 2005.

Like other children from Room 10 who landed in a new town or city, she got harassed and she fought back. Imagine being dropped into a new school after experiencing the worst trauma of your young life and being called a refugee, a water baby, or worse. You walk the halls wearing whatever clothes your parents could scrounge together from shelter donations, the other kids laughing at your New Orleans accent and asking time and again whether you really saw dead bodies floating in the water.

Before Katrina, Akia had always imagined a life designing clothes or teaching or helping people as a nurse. “I’d be out of school,” she says. “I wouldn’t be struggling to get my GED. I wouldn’t be working at McDonald’s. After Katrina I just didn’t care.” Still, she has a kind of boundless natural energy. And she’s trying to move forward.

Tiaona Torregano, who is eighteen, is as shy as Akia is outgoing. Though she, too, had trouble coping in the wake of Katrina, a combination of support from relatives and educators proved to be especially crucial to helping her recover. She started at Phillis Wheatley when she was in pre-K, when she lived with her mom in the Lafitte projects. Her mother hadn’t finished sixth grade. Tiaona would often visit her dad and grandmother Leah Augustine in the Gentilly neighborhood. When the storm approached, the extended family assembled at her grandmother’s house and jammed into as many cars as they could find. Her mother, who had long been estranged from her father, stayed back. (Eventually, her grandmother’s home would be submerged in ten feet of water. It would take years to rebuild it.)

The family managed to get into a Hilton hotel, but soon the building started shaking. Windows blew out. Tiaona remembers her dad snatching her back just as she was about to get lost in the crush of a crowd rushing through the hotel halls. When the levees broke, they headed north. Everyone had someone on his or her lap. They were in the car for hours, eventually landing in Chattanooga, where a church adopted them.

Through it all, Tiaona thought her mother was surely dead, drowned in the waters of New Orleans—until a week later, when her father found her mother on a website dedicated to reuniting families. She was in Texas. After a month and a half, that’s where Tiaona headed, too. “I couldn’t get right until I saw her,” she says. “Then I just remember feeling peace.”

Her grandmother, a longtime New Orleans educator, made sure no one missed any school and eventually got most of the family back to New Orleans. Tiaona moved back in with her mom, but she was struggling with schoolwork. As with many students who had lived through the storm, teachers had her write papers about it, but she couldn’t seem to recover. She was getting Cs and Ds and crying almost daily.

When Tiaona started sixth grade, she moved in with her grandmother. Finally, a teacher found a way to reach her. They talked about the storm, she remembers, about how to put it into perspective, about focusing on herself and her studies. “Even if I cried, she pushed me,” Tiaona says. “She stuck by me and motivated me.”

This past May, she graduated from high school with honors and is headed to the University of Louisiana at Lafayette to study speech pathology. She wants to work with young children. Rarely a day goes by, though, that someone in the family doesn’t talk about Katrina. “Even though I’ve moved on and I’m past it, the memory is still fresh in my mind like it’s new,” she says.

Ten years on, Bruce Jordan, a budding young football star, is another child who has managed to get his life back on track after it was upended by the storm, in ways that now seem cinematic. He was just a boisterous child in the Lafitte projects before Katrina, playing “it”—what kids in New Orleans call tag—and watching women fixing one another’s hair on the wrought-iron balconies.

Bruce hasn’t spoken publicly about the details of what happened to him and his mother during the storm, but shortly after, they ended up in an Uptown neighborhood called Central City. Although most people who lived in New Orleans’ high-poverty neighborhoods like the Sixth Ward knew someone whose family had been touched by murder, it was a whole different game in Central City. At least Lafitte had a sense of community. Here it was like the Wild West. Many of the city’s most traumatized people had moved in, and there were so many murders, the neighborhood came to symbolize the worst of post-Katrina anger and violence.

About five years after the storm, Bruce wandered into the gym where Patrick Swilling, a former star New Orleans Saints linebacker, was holding tryouts for his youth basketball team. “He had no basketball attire and didn’t own tennis shoes,” Robin Swilling, Pat’s wife, told a reporter for the Clarion Herald, the official newspaper of the Archdiocese of New Orleans, in 2014. “He was trying to work out with the team in boots.”

Pat has said he immediately saw Bruce’s athletic potential and began working with him. The Swillings would come to learn that Bruce’s mom, who has since died, could not care for him properly. They eventually took over guardianship and are adopting him.

Handsome and six foot two, Bruce is developing into a star running back at Brother Martin High School and already has offers from the Oklahoma Sooners and the Miami Hurricanes to play football. Others are sure to follow. Pat Swilling declined our request for an interview with Bruce. He had been through so much and was in a good place now, Swilling said during a brief phone conversation.

People who have taught Whitney Walls, at eighteen a beautiful, bright young woman who likes to sing and adores her father, say she is a good example of the cognitive hit endured by many of the children who were young when Katrina came.

When the storm water crept in under her front door, she fled to the convention center with her mother and her family. They climbed in someone’s truck and drove. She spent a year in Houston, and like other displaced children from Room 10 felt adrift and isolated.

She’s a quiet, logical thinker who copes with type 1 diabetes and other health issues. She was so behind after Katrina she ended up repeating fourth grade. Through it all, her mother has battled substance abuse, which is still perhaps the worst wound in her life, she says.

Whitney is on track to graduate next year from Warren Easton, a long-revered New Orleans high school that served as an impromptu shelter during Katrina and whose alumni and a generous donation by the actress Sandra Bullock helped save after it was damaged by the storm. But school has not come easy for Whitney.

Whitney’s sophomore English teacher, Lauren LeDuff, watched her struggle, and worked closely with her and other Katrina kids. By the time they got to high school, LeDuff says of the children who were just beginning their elementary education when Katrina came, it was clear that they had missed a vital period of cognitive learning. “These children were at the stage where they were learning rigor,” she says. “They were just learning how to learn, and that process was blown up.”

Lori Peek, the sociologist who is studying the children of Katrina, says one lesson from the storm is that students who experience a disaster need to get back into school quickly. “When young children miss a month or more of school, they need the best teachers possible so they can make it up,” she says. “These kids had none of that.”

Room 10 disappeared entirely in the summer of 2011, when the decrepit Phillis Wheatley was finally torn down. Built in 1954 as a segregated school and named after a girl who was enslaved at seven years old but went on to become the nation’s first published African American poet, it had been considered a midcentury architectural jewel and certainly the heartbeat of the neighborhood. A mix of preservationists and neighborhood activists fought its demolition, but plenty of longtime Tremé leaders were anxious to start a new chapter, including Leah Chase, the renowned ninety-two-year-old Creole chef and neighborhood matriarch whose restaurant, Dooky Chase’s, sits across from the site. She watched it fall, and in its place arise a new $26 million building almost three times as big as the old school. Murals of scenes from the neighborhood mark a soaring atrium. There are three floors of classrooms and space for an edible garden. The cafeteria smells like fresh oranges and hot, soft yeast rolls.

The sankofa, an African symbol of a bird appearing to look back over its shoulder, hangs near the front door, where children in gold-and-black uniforms stream in. “It means you look back as you move forward,” Chase says. “We said we wanted a state-of-the-art school, and we got it.” Inside the charter school, educators are trying to make a new and highly politicized approach to education in New Orleans work. Today, about 90 percent of the city’s children attend charter schools.

Diana Archuleta, the principal of what is now called the John Dibert Community School at Phillis Wheatley, is constantly balancing the needs of the neighborhood children with those of students who are coming in from other parts of the city. The ones who went through Katrina still stand out, she says. In the five years she has been working with students as part of the new charter system, she has had to make tough decisions, such as hiring extra counselors instead of teachers.

Linda St. Martin-Scott, the teacher who had spent thirty years at the old Phillis Wheatley and whose students we had been searching for, stepped into the new school for the first time this spring. It was a bittersweet moment. She marveled at the facility but worried that it didn’t seem as homey and warm as the old school. Did the new teachers know the students the way she and her fellow teachers had? Did they understand that you couldn’t begin to educate a child unless you first listened to the traumas she might have witnessed at home the night before?

Photo: Rush Jagoe

Hakeem Carter

And she wondered about the students who never came back to Room 10. “I want to know, did they get out of the Katrina water?” she says. “Was their family safe? Were they able to find good teachers to take them to greatness?”

For Hakeem and Jonathan, the two boys who bonded over Hubba Bubba in the Lafitte, the storm remains a drama they retell as if recounting a movie. Hakeem’s family made it to the Superdome after three or four days stranded in the projects. Then things got scary.

Hakeem’s mother’s boyfriend at the time was an older man in a wheelchair. He and Hakeem were tight, so when they had a chance to get on a helicopter evacuating the sick and handicapped to Shreveport, Hakeem’s mother, Dorothy Carter, sent the boy along to help push the wheelchair. Hakeem was terrified of heights. “It was hell,” he says.

He had to repeat third grade, and recently graduated from a trade school. He wants to open his own electronics business. For the most part, Hakeem says, he keeps to himself. “I like to stay out of the drama.” By which, he says, he’s referring to the violence in his Sixth Ward neighborhood.

The sadness of the storm hangs over him, mixing with fresh pain that came a few years ago when his older brother was shot and killed on the family’s front porch the day before he was to head to college on a baseball scholarship. His dreadlocks are woven into a necklace Hakeem wears every day. He watches TV most of the day, and he chews on his fingers. It’s his nerves, his mother says.

For Jonathan, his mother, Gail, is the hero of his movie. Stranded at the convention center for maybe three days or longer—no one can quite remember—she shielded her children when people died on the sidewalk next to them. She made sure they had soap and water so they could wash up, even if it was on a sidewalk behind a sheet someone held up. She hustled them off the Crescent City Connection bridge over the Mississippi River when someone was shooting at people trying to get to dry ground in Algiers.

Finally, Gail had enough. When she saw a city bus that a man had commandeered coming her way, she ran out in front of it, waving her arms. She carried 389 pounds on her five-foot-seven frame. There was no way, she thought, this man was going to plow her down. He stopped. She said she was a city bus driver.

“I told him I could get us out of the city if he let us all on that bus,” she says. They took turns driving to Lafayette, where they ended up in a shelter set up in the Cajundome.

“The whole time she was just like, I got you,” Jonathan says. “She’s still that way.”

He turned nineteen in May and managed to graduate even though his grades were right on the edge. One day, he says, he’ll write movies. He is especially attracted to zombie thrillers. But for the summer, all he wants to do is visit New Orleans again. And see Hakeem.