Things are heating up in Oklahoma’s corner. Under a soaring white event tent, Austin Morton is threading dove hearts onto rosemary skewers. Ray Penny is searing a ten-inch chunk of elk loin and finishing a wild mushroom cream sauce in a cast-iron skillet. He takes a quick peek inside a cooler. A flan made from crappie roe should be just about set.

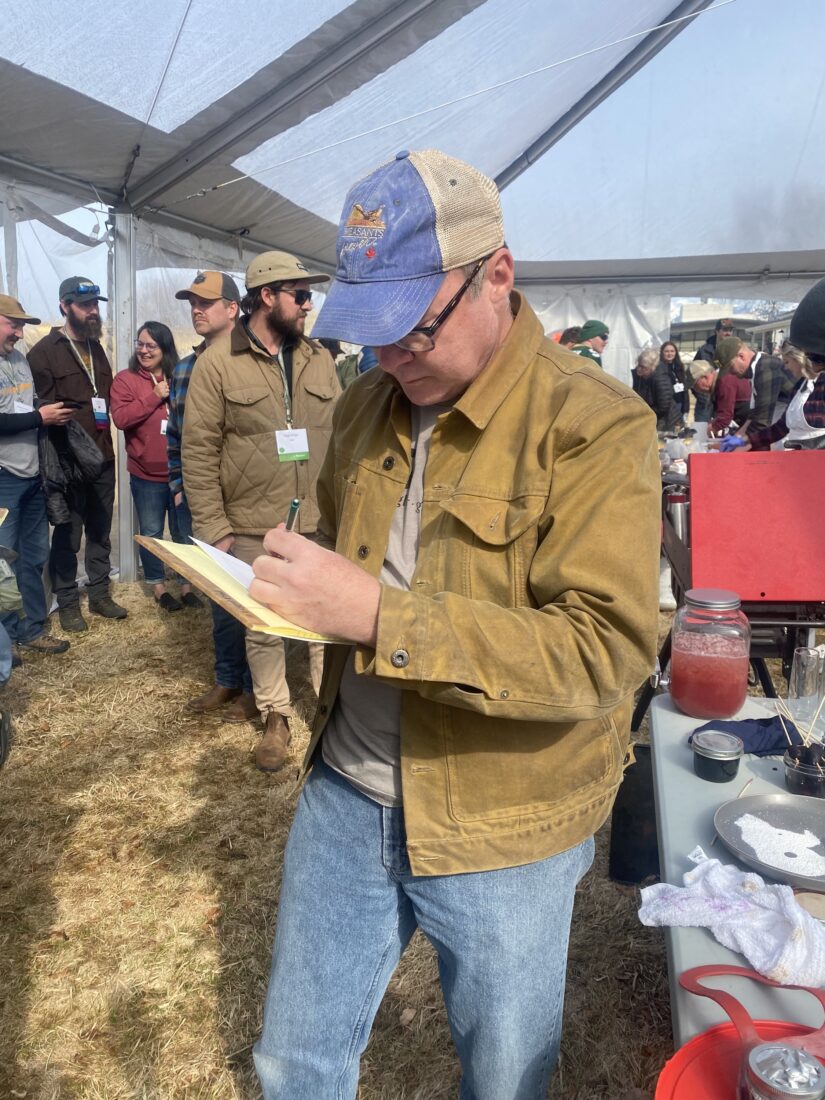

A man steps up, holding a clipboard and wearing a name-tag lanyard. “Twenty minutes,” he says, giving a thumbs-up. Penny nods and wipes a bead of sweat from his forehead.

The tent is a hive of activity. Wild game cooks at ten cooking stations are bent over a bewildering array of game meats, foraged greens, and camp stoves. It’s Arizona in another corner, where Mearns’ quail and Mexican duck breast rolls rest on a dove and duck chile salsa. Ten feet away, in California, yucca flowers adorn chunks of steamed spiny lobster. Foraged morel mushrooms simmer in an elk bone broth.

I’m at what is arguably the world’s most impressive game cooking contest, the Wild Game Cookoff held each spring at the annual Rendezvous of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers (BHA), the country’s leading advocacy group for public lands, waters, and wildlife. On the fairgrounds of Missoula, Montana, teams from ten states vie for a space on a coveted awards plaque and bragging rights for a solid year. The main ingredients in each entry must be representative of the respective state, and two-person chef teams have one hour to complete a meal with enough servings for five judges. Presentation and creativity are paramount.

Wandering the tent, I was drawn to Team Oklahoma’s entry, not only because Penny and Morton were the only contestants from the South this year (the roster has included teams from North Carolina, Florida, and Kentucky in the past) but also because their offerings were something I thought I could replicate. A centerpiece of their plate was an elevated preparation of a Southern staple: crappie, served on the half shell in the manner of a Louisiana redfish, pan-sauteed in duck fat, topped with a smear of wild-onion compound butter, and finished with a dollop of paddlefish caviar. I loved the presentation: Each crappie tail had been cut off at its base, battered in acorn flour, and deep fried. Placed upright between the crappie fillet and the team’s elk tenderloin, the tail fin literally crowned the plate.

Panfish on the half shell—I should have thought of this a decade or three ago.

The Oklahoma team hailed from G&H Decoys in Henryetta, a company that has been manufacturing waterfowl decoys for eight decades. Penny is an avid hunter, angler, conservationist, and the CEO. “We all love being from Oklahoma, and we wanted to tie the geography of the state together in one meal,” he says. The elk loin came from Cimarron County, Oklahoma’s westernmost county. The wild mushrooms are from Adair County, on the state’s eastern border.

“Growing up,” says Morton, president of the Oklahoma state chapter of BHA, “you got presents on Christmas and your birthday. The rest of the year, we showed love by cooking for each other. And that’s what we’re trying to do here: Show a little Oklahoma love.”

In the end, despite my silent cheering, Oklahoma came up just a bit short in the contest. The winning entry, from Washington state, featured a venison backstrap with wild morel gravy and fresh nettles, and a huckleberry steamed pudding.

But I couldn’t shake Team Oklahoma’s fish, and Penny and Morton were kind enough to share the recipe. It works equally well with crappie, farm pond bluegill, redbreast sunfish, and the like, and it might just be the best panfish recipe on the planet. The preparation gives a sophisticated tip of the hat to the saltwater staple of cooking a fish fillet in its skin. The compound butter is made with lemon and fresh foraged wild onions or ramps (you can substitute store-bought chives). The paddlefish caviar came from Oklahoma, but any quality caviar will work. There’s nothing wrong with a dollop of crappie or bluegill roe, either.

Follow T. Edward Nickens on Instagram @enickens.