Berea, Kentucky

“People have been coming to Berea for craft for a hundred and twenty years,” says Michelle Weston, who for decades has been transforming 2,050-degree molten glass into captivating, often aquatic-themed sculptures—jellyfish, tide pools, seahorses—at her Weston Glass Studio. Since the 1890s, folk arts and crafts have served as the beating heart of this Kentucky hamlet that edges the Appalachian foothills about forty miles south of Lexington.

The town grew up around the leafy campus of Berea College, a much-admired (and tuition-free) liberal arts “work college” founded by abolitionists in 1855, with a deep-rooted craft tradition of its own. (The New Yorker once described it, rather bluntly, as a school “for the academically talented but economically strapped.”) Many of the local creative professionals are Berea graduates who stayed put. The place “continues to have that allure,” says Todd Finley, executive director of the Kentucky Artisan Center, a limestone mega-gallery that stocks a dizzying variety of artworks—from duck calls to patchwork quilts—by more than 850 makers. “It’s just a really cool little town.”

It’s also, arguably, a town that should come with a warning label, since strolling around its two-dozen- plus studios and galleries tends to stir up acquisitive urges for handcrafted treasures: a Shaker-style table of walnut topped with streaky ambrosia maple, say, at Top Drawer Gallery in the Old Town Artisan Village. Or a handwoven broom or an ash-and-cherry rocking chair made by Berea students at the college-owned Log House Craft Gallery. For the horse breeder who has everything, the Artisan Center has on hand a life-size Thoroughbred that a veterinarian conjured together with wire fencing salvaged from Kentucky farms—yours for $54,000.

But Berea also stands out for the way it welcomes visitors both to watch artists at work and to join in themselves. A series of “Learnshops” offer instruction in watercolors, blacksmithing, gourd art, glassblowing, you name it. The Berea Makerspace gives members access to equipment like woodworking tools, 3D printers, and welding torches. And after hours, artisans, students, and visitors alike mingle at a downtown space that begins each day as Native Bagel Co. and then morphs into its buzzing evening incarnation, Nightjar, serving cocktails named after birds and smash burgers sourced from (where else?) Berea College Farm. —Mike Grudowski

Center Point, Texas

Marfa may be one of the most celebrated Lone Star art destinations, but roughly 350 miles to the east, set among cypress-shaded limestone pools, another small town is making its mark. In 1859, Center Point was established along the Guadalupe River in the middle of intersecting trade routes and remained a vibrant commercial hub until the 1920s, when a new highway siphoned traffic away from downtown. A century later, this once-bustling crossroads is undergoing an art-focused revival, thanks in large part to the Houston-raised, New York–based interior and architecture designer Sara Story. “I have always believed that art can start a dialogue,” she says. “There is so much natural beauty in Center Point, and so much kindness and love in its residents, that I think it’s only natural that it’s evolving into an up-and-coming art community.”

Last year, Story and her family opened Center Point Art, a gallery and artist residency in a nineteenth-century bank building. A twenty-five-foot sculpture of a girl crowned by a towering tree anchors the exterior, a whimsical piece by the Japanese artist Yoshitomo Nara. Inside, chairs by Donald Judd and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe offer a chic, modernist pop in the historic space. Last fall, inaugural resident artist Matt Tumlinson premiered Limestone Muse, a collection of mixed-media Texas landscapes rendered in oil and salvaged cedar scraps; next, the contemporary Ghanaian artist Joseph Awuah-Darko’s exhibition opens in conjunction with the total solar eclipse on April 8.

Story and her family spend holidays at their nearby ranch and often grab picnic supplies at Central Provisions or catch live music over spicy Palomas at Zanzenberg Tavern. Just a few miles away in Comfort, lodging includes the historic boutique inn Hotel Giles and Camp Comfort, an 1800s athletic club and bowling alley turned Hill Country getaway with suites, cabins, and even a renovated Spartan trailer for retro summer-camp vibes. —Sallie Lewis

Orange Beach, Alabama

Along the Gulf of Mexico, it’s tough to compete with the built-in artistry of sugar-white shores and glittering turquoise waters. But in little Orange Beach, Alabama, creatives thrive. “There’s a vibrant, expressive spirit here,” explains Maya Blume-Cantrell, the resident clay artist at the Coastal Arts Center, as she talks glazes with visitors. The center’s sunshine-soaked gallery showcases that talent, selling the works of dozens of Gulf Coast makers, and its classes in pottery, watercolors, photography, and oils—as well as glassblowing at the Hot Shop—nurture present and future artists.

A short drive away, at Pier House restaurant, paintings of moody, surf-reflected sunsets in the attached gallery by Connie Chapman, the chef ’s sister, draw as many fans as the super-stuffed fried-oyster po’boys. Even at a spot called Tacky Jacks, guests can sip frosty Bushwackers while taking part in decoupage workshops under the tutelage of a local graphic designer.

High notes on the coastal-Alabama arts agenda include spring’s Orange Beach Festival of Art, which marks its fiftieth anniversary this year, and the Frank Brown Songwriters’ Festival each fall. Over those eleven days, more than 175 musical artists put on shows in Orange Beach and neighboring Gulf Shores and at the famed Flora-Bama Lounge.

But the year-rounders are the ones who really keep the scene afloat. Their works fill the Salty Palm boutique, the Pink Pelican gallery, and the Sea Oat Studio in Gulf Shores, where husband and wife Steve and Dee Burrow make their wood-fired stoneware. At Swiger Studio, botanical images fashioned from cigarette filters and plastic refuse pulled off the sand turn trash into treasure and encourage respect for all creatures that call the beach home. Blume-Cantrell’s husband, Nick Cantrell, an artist who uses melted wax and watercolors to depict sea turtles, pelicans, and beach scenes, says that the area’s creative tide is rising. “There’s always been an art undercurrent here; now it’s swelling,” he says. “The coast pulls in people who trade in beauty.” —Jennifer Kornegay

Covington, Louisiana

The Bogue Falaya lazily rolls by the tidy village of Covington, with its low-slung downtown and well-kept bungalows, about an hour outside New Orleans. In the park by the bayou stands a statue of the novelist Walker Percy, who lived in town from 1948 until his death, in 1990. The statue, by sculptor Bill Binnings, depicts a larger-than-life Percy leaning against what appears to be a doorframe, peering quietly around its edge.

That’s as good a symbol as any for the connection between Covington and the artistically inclined, who have had a foothold here since the middle of the last century, establishing a scene that tends toward the sedate, as if preferring shadows over spotlight. It’s seemingly designed by artists for artists rather than for gawkers and those who put on airs; it was once referred to as “Soho on the Bogue Falaya.”

In 1958, residents founded the St. Tammany Art Association to make the parish a more welcoming creative hub. The group has steadily grown and today operates out of the downtown Art House, a historic building that serves as both a gallery for area artists and a place for workshops. “We’ve had galleries come and go, but the art association has been a sustaining presence in town,” says its vice president, Keith Villere (he’s also a former three-term Covington mayor).

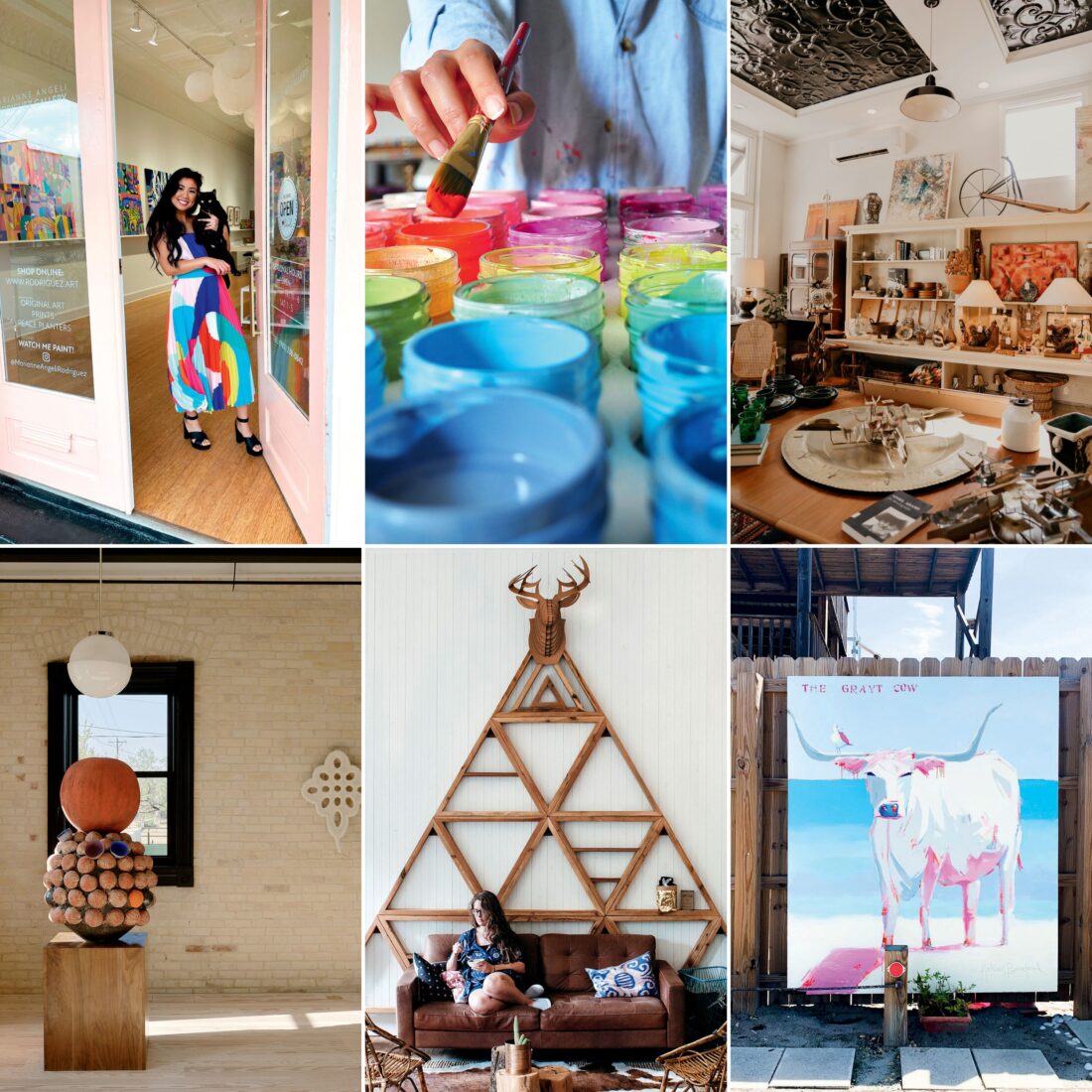

Art walks link venues on the first Saturday of each month, and downtown shops—such as the Saladino Gallery, which represents local artists, and the Marianne Angeli Rodriguez Gallery, which sells Rodriguez’s colorful paintings, prints, and pottery—serve those visiting in between. Each November, the town fluffs its plumage and foot traffic swells for the Covington Three Rivers Art Festival, a two-day juried showcase of some two hundred artists. But quiet remains the prevailing melody. Percy once said that he liked Covington because it wasn’t exotic or on anyone’s beaten path and was perfect for someone who wanted to write with as few distractions as possible. A place, in Percy’s words, “to listen to the frogs tune up.” —Wayne Curtis

Grayton Beach, Florida

The Florida Panhandle’s 30A corridor draws art lovers of all tastes: Festivalgoers flock to ArtsQuest, one of the Southeast’s top juried shows, while Digital Graffiti, a weekend extravaganza at ritzy Alys Beach, pulls an architecture-loving crowd. But any arty itinerary along 30A should include Grayton Beach, the eclectic enclave that birthed the arts scene along this entire stretch. Founded in the 1880s, Grayton—its natural beauty marked by serene dune lakes and swaths of pine and oak, much of it protected as state parks and forests—has long attracted painters, sculptors, and photographers who set up shop in wooden bungalows along the beach. Some original cottages remain among the vacation rentals, their whimsical yard curios peeking through Spanish moss.

At Defuniak Street and Hotz Avenue, a trifecta of landmarks reflects an Old Florida spirit and the com- munity’s artistic core: the Grayt Wall of Art, where a mural proclaims the unofficial motto, NICE DOGS STRANGE PEOPLE; the weathered Red Bar, whose hodgepodge of memorabilia and tchotchkes makes it as much time capsule as restaurant; and the Zoo Gallery, with its delightful and downright weird art. Opened in 1979, the Zoo has three Panhandle outposts; its Grayton location offers to visitors three rentable rooms above the shop. A few miles north, the colorful Shops of Grayton, a collection of eight galleries, have promoted local talent since 1998.

The origins of 30A’s event circuit began here too. In 1988, photographer and custom-frame shop owner Susan Foster cofounded the Grayton Beach Fine Arts Festival with her friend Jan Clarke. Its early years typified Grayton’s wild-child personality, with pony rides and a giant pig to pet, someone strumming a guitar, and dogs running around everywhere. “It was very much a small community event,” Clarke says. “There was a lovely bond, and a lot of friendships were formed.” The festival soon obtained state funding, evolved into the multiday ArtsQuest, and helped inspire the Cultural Arts Alliance of Walton County, an organization that named its Foster Gallery in honor of the late photographer. Her tiny frame shop may be long gone, but the legacy she left shows no signs of fading. —Blane Bachelor

Wetumpka, Alabama

While Erin and Ben Napier put the spotlight on this Alabama town on HGTV’s Home Town Takeover in 2021, this community has long been using its storied past to create quirky works of art, like hand-carved river snails, giant fish, steampunk-inspired metal sculptures along its riverwalk, and even a mural featuring an Appalachiosaurus dinosaur, whose ancient fossils were discovered in the area nearly fifty years ago.

The nationally recognized Marcia Weber Art Objects gallery stands in the center of Wetumpka’s historic district. Weber started her gallery in 1991, after being introduced to the prominent blues musician and early master of Southern art Jimmy Lee Sudduth in the 1970s and living down the street from the heralded folk artist Mose Tolliver as a graduate student in the 1980s. “Mose T’s home studio became a destination for many who were on folk art journeys through the South in the 1980s and 1990s,” Weber says. “When my home grew overfilled with this art, I couldn’t stop visiting and collecting from these amazing artists who, by then, had become cherished friends. It was a natural progression for me to start a gallery to find other caregivers for self-taught art.” Weber’s gallery is filled with more than 1,000 rare and unusual one-of-a-kind works and features renowned artists such as Della Wells, Woodie Long, and Bill Traylor.

Another Wetumpka gallery inspired by the town’s natural landscapes is the Kelly Fitzpatrick Memorial Gallery, which recently announced the Wetumpka Wildlife Arts Festival. The fest includes a series of classes, art exhibits, and expert demos by award-winning artisans including chef Chris Hastings, sporting and wildlife artist Dirk Walker, and Wildrose Kennels, the largest breeder, trainer, and importer of British and Irish Labradors in North America. The series celebration will take place intermittently from September 30 to November 17, with a signature daylong event on November 5 on the banks of the Coosa River. —Jenny Sue Stubbs

Lake City, South Carolina

Each April, this town turns into a gallery during Artfields, Lake City’s flagship event which consists of local businesses displaying hundreds of works of art as artists compete for $100,000 in prizes. This historic community in the northeast corner of South Carolina embraces its deep agricultural roots by implementing native flora throughout its downtown, complementing the varied colorful, expressive art pieces found there, like the sixteen-foot “Make a Wish” dandelion sculpture. —Jenny Sue Stubbs

Pittsboro, North Carolina

In the Piedmont region of North Carolina, Pittsboro’s annual Fearrington Folk Art Show in February showcases many self-taught artists. R.B. Fitch, who owns Fearrington House Inn, Restaurant and Village, has infused the property’s historic grounds with art since taking ownership decades ago. And after meeting artist Sam “the Dot Man” McMillan about twenty years ago, Fitch envisioned a small art show in the Fearrington Barn, with no booth fees nor commissions expected from participating artists. Nineteen years later, it’s now one of the region’s most anticipated annual events.

Kerstin Lindgren, co-coordinator of the art show, explains the intentional community engagement. “The folk art show welcomes about thirty-five artists each year, and they come from all over the eastern U.S. mostly, but it’s always been especially important to us to draw from the rich self-taught art traditions here in North Carolina. We host artists from right here. Even before the Fearrington Folk Art Show, there has always been a vibrant arts community in Pittsboro and Chatham County. We’ve just provided another way for the public to enjoy and think about art in an approachable way.” —Jenny Sue Stubbs

Natchitoches, Louisiana

Say it with me: nak-uh-tish! The art and heritage preservation of this historic Louisiana town has helped it flourish for generations, and its art origins are certainly worth celebrating. Home to the longstanding event Melrose Arts & Crafts Festival each April, this area is the birthplace of Clementine Hunter, an acclaimed folk artist who contributed to the town’s legacy of veritable art appreciation and cultivation. —Jenny Sue Stubbs

Thomasville, Georgia

After twenty years of hosting the successful Wildlife Arts Festival every fall, this town holds its own when it comes to infusing art into the landscape of its community. The popular affair coincides with the start of Georgia’s quail season and offers a fine arts show, experiences honoring the land, workshops, and an unveiling of public art to celebrate its local ecosystem. The wildlife painter Sue Key was featured at its most recent festival, where she shared a journal of her memories—of water and the light filtering through pine trees—before she captured beauty in paint. —Jenny Sue Stubbs