After I plucked and gutted the Arkansas greenhead, and snipped off its wings and feet, I had a little more knife work to do. I sliced off a quarter inch of the mallard’s tongue and placed it in a vial filled with preservative. Back home in North Carolina, I would mail the vial to Texas, where an innovative partnership between Ducks Unlimited (DU), the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP), and hunters is untangling the convoluted genetics of the continent’s most iconic duck species. Just over a year into the study, the data so far is unsettling: Mallards in eastern North America are a bit of a mess.

More to the point, the region’s mallard family tree looks more like a weedy garden than a single trunk branching into well-ordered ancestry. Recent genetic research, including the duckDNA study that I and some three hundred other hunters participated in last season, has revealed an alarming amount of game-farm mallard genes in the wild mallard population. They were found in 71 percent of Atlantic Flyway samples, nearly a quarter of Mississippi Flyway mallards, and 12 percent of the Central Flyway birds. The percentage in Great Lakes birds is climbing rapidly.

The culprit: releasing game-farm mallards for hunting, a practice more than a century old. In the Atlantic Flyway alone, millions of the European-stock birds have flown into the wild, cast loose by state agencies—which have since halted doing so—and hunting clubs. For decades, most assumed these farm-raised mallards wouldn’t interbreed with the wild ones, at least not to a concerning degree. Then, in 2019, scientists discovered so-called “mystery genes” in mallards from across North America, later determining they came from game-farm ducks. In subsequent flyway-specific studies, those genes popped up in North Carolina and South Carolina birds. Next, in 2022, low levels of the genes turned up in Mississippi Alluvial Valley mallards, and a year later, in Great Lakes birds, at higher levels.

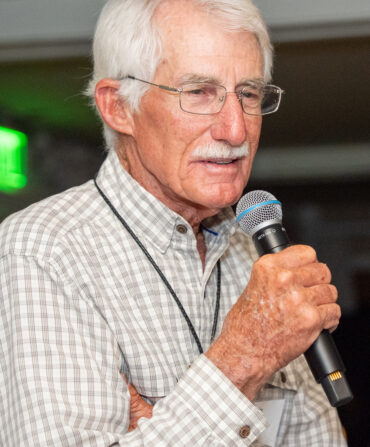

To help quantify the incursion, the duckDNA program that kicked off last year will more than double in size during the 2024 to 2025 hunting season. Led by Philip Lavretsky, a UTEP associate professor of biological science, and supported by DU’s hunter outreach, the project includes more than seven hundred hunters countrywide who have volunteered to collect tissue samples from mallards and suspected hybrid ducks. The first year of the project uncovered nineteen hybrid combinations in the 721 ducks sampled.

“Those feral game-farm birds are out on the landscape, and they are breeding,” Lavretsky says. Game-farm mallards typically have shorter and broader bills, better suited to pecking at feed rather than filter feeding in the wild. Those traits could lead to less efficient foraging, a higher risk of predation, and a lack of nutrition for migration and reproduction. Game-farm birds also seem to put on less fat than wild mallards and don’t exhibit the same migratory tendencies. And they are three times less likely to finish incubation.

Scientists debate whether and how much such differences relate to population trends; the new research will aim to plumb those kinds of questions. But science is a process. “We are still in the learning phase,” explains Mike Brasher, DU’s senior waterfowl scientist, in the hopes of developing “a fuller picture of this issue.”

Thankfully, genetic swamping can be reversed. It takes only two or three generations of backcrossing with wild mallards to effectively wash out the polluted genes, Lavretsky reports, and a huge population of wild mallards still exist. But for that method to be most effective, game-farm releases would have to stop.

While that decision largely falls to state and federal agencies, Brasher says that for DU, “we’re excited about tapping into the passion of waterfowlers to be involved in the scientific process.” Hunters have long taken part in such citizen-scientist efforts, from returning leg bands to collecting some ninety thousand duck wings for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s waterfowl populations analysis. “Now we’re coming into another arena with genetic studies,” Brasher says.

Lavretsky agrees. “It would cost a zillion dollars to have technicians monitoring populations like this at a continental scale,” he says. “This project showcases one more way that hunters are conservationists.”