Some of the most imaginative artwork comes from experimentation and fierce curiosity—and from visionary Southern women. Quilter Lucy T. Pettway and contemporary multimedia artist Suzanne Jackson, for example, expanded the field of visual arts through innovative exploration. Pettway and the women of Gee’s Bend in Alabama tapped into generations of stitching knowledge to create complex, rippling patterns from fabric scraps; in her studio in Savannah, Jackson’s fantastical, colorful sculptural works float without a canvas.

But women in the arts haven’t always been given their due respect. For decades, critics and audiences overlooked their work in the male-dominated sphere, considering women’s talent as domestic crafts rather than artistic mastery. The Speed Art Museum’s program Kentucky Women hopes to reframe the narrative to embrace Kentucky artists who were largely unnoticed during their careers. The first show, spotlighting sculptor Enid Yandell, debuted at the Louisville museum in 2019, but the concept for Kentucky Women had been on curators’ minds since 2015, when the team presented a traveling exhibition on women Impressionists in addition to a permanent collection show focused on early-twentieth-century female artists.

“During all that planning [for the traveling show], we realized we had a responsibility to be sharing the stories about the women artists, advocates, and collectors who helped build and shape the state’s art history,” says Erika Holmquist-Wall, the Speed’s chief curator. The rotating program allows the museum to look back to artists forgotten in Kentucky’s history, bringing them forward to new audiences.

The latest exhibit, Kentucky Women: Alma Wallace Lesch, honors the artist and educator who paved the way for fiber arts in the state. From the sixties until her death in 1999, Lesch pushed the traditional boundaries of needle arts. Rather than limiting the form to domestic tasks, she embroidered, quilted, and stitched together elaborate, layered fiber work inspired by her surroundings in her rural homeplace of McCracken County. She physically infused the Kentucky landscape into her fibers as well, coloring fabric with natural vegetable dyes and native plant material. Eighteen pieces, ranging in size and material, will be on display until October 29.

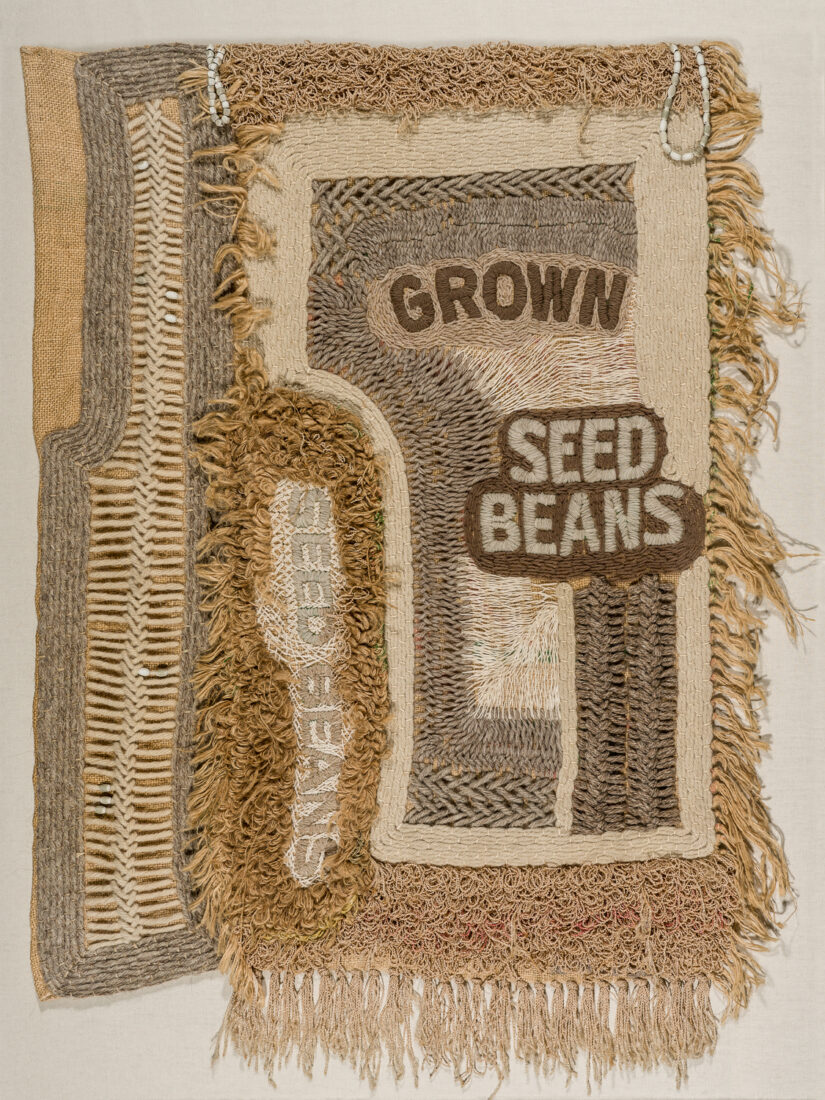

Lesch believed in the power of found materials, seeking out textiles from local estate sales to incorporate into her work. “It was a way of capturing a kind of humanity in her work,” says Scott Erbes, the curator of decorative arts and design at the Speed. The pieces Variations on the Theme of Seed Beans and Ful-O-Pep, both of which are included in the show, exemplify Lesch’s ability to revive old material, like seed and chicken feed bags, and imbue them with rich meaning. Ordinary, discarded objects become a tribute to everyday life in the hands of Lesch, who blended them into a tapestry full of painstaking pattern and texture. “She gave found materials a different kind of second life, elevating them with intentional reworking,” Erbes says. “She used the rural life she was familiar with and created a pop-art quality, incorporating corporate branding and considering its place in American visual culture.”

Her signature “collage fabric portraits” embody her penchant for abstraction and representing women in her art. “When you see what she was doing—often using found materials and traditional needle techniques—she was taking this long history of women’s art production with the home and domesticity and moving it into the contemporary art world,” Erbes says. In Lillian, named after a town local, Lesch surrounds old clothing in a circle of mauve buttons, creating an abstract, faceless woman. In another fabric portrait, she incorporates her own high school graduation dress from 1934, exploring the line between fiction and autobiography. For Lesch, reusing discarded items offered “a way of capturing a kind of humanity in her work,” Erbes says. “She once told a local newspaper, ‘The things that people throw away are much more interesting than what they keep.’”

One of Lesch’s greatest legacies is her teaching work at the Louisville School of Art and the University of Louisville in the sixties and seventies. “She said there wasn’t a certain way to do something, and encouraged students’ own creativity and innovation with fiber materials and techniques,” Erbes says. “She was always one to tell them, ‘Let the material speak to you.’”

Gabriela Gomez-Misserian, Garden & Gun’s digital producer, joined the magazine in 2021 after studying English and studio art in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. She is an oil painter and gardener, often uniting her interests to write about creatives—whether artists, naturalists, designers, or curators—across the South. Gabriela paints and lives in downtown Charleston with her golden retriever rescue, Clementine.