As I tug on chest waders on a sweltering September day to enter a cypress knee–studded swamp in Charleston, South Carolina, retired biologist John “Billy” McCord ticks off a safety rundown: “Drink water. Walk on fallen logs to reduce your chances of stepping on a copperhead. Don’t pass out, because I don’t want to drag you out of here. When you trip over a cypress knee, be ready to hit more on the way down. And, most important: When you’re not looking down at your feet, scan the landscape for monarchs.”

McCord’s passion for monarch butterflies has led him through swamps such as this one, barrier islands, and other Lowcountry environs hundreds of times since he began researching them nearly thirty years ago. And despite the iconic species’ status as one of the most-studied insects in the world, the Manning, South Carolina, native has uncovered a surprising new facet to the vulnerable pollinator’s story: A population of Lowcountry monarchs appears to thrive here year-round, rather than carrying out the species’ typical migration pattern.

For more than a million years, monarchs have cycled from egg to caterpillar to chrysalis to butterfly. In North America, the Rocky Mountains divide them into Western and Eastern populations, with the latter achieving the most astounding migration in the insect world: After overwintering in the oyamel fir trees of Michoacán, Mexico, they make the return journey’s first leg up into Texas, breed, lay eggs on milkweed, and die. Those caterpillars undergo metamorphosis, fly farther north, and repeat; it can take three to five generations to reach Canada by summertime. Then, a monarch super generation that lives eight months instead of five to six weeks rides the wind all three thousand miles back down to Mexico, to light upon the same trees as their ancestors did the previous winter.

In 1996, McCord, who then worked for the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR), tagged his first monarch with a small circular sticker from the University of Kansas, which has long compiled tracking data. Soon, he started noticing strange behavior: He spotted and caught monarchs in the winter, when they should have been in Mexico, and eventually documented the butterflies in the swamps of every major rivershed in the state—including the Waccamaw, the Santee, the Edisto, the Ashepoo, and the Savannah—habitat not previously associated with them. He also observed mating pairs throughout the fall, despite the conventional knowledge that the butterflies did not mate during their southerly migration. And he identified eggs and caterpillars on Gulf Coast swallowwort, a milkweed relative, in the salt marshes.

“I knew we had to get this story out,” says Michael Kendrick, a scientist with the SCDNR. “Billy had been working on this for such a long time, and he was starting to describe larger trends that broke with what we thought we knew.” The duo collaborated on a five-year study of 18,375 monarchs, with McCord in the field tagging and Kendrick spearheading project design and data analysis. Their findings confirmed McCord’s observations: Monarchs are populating Coastal Plain swamps during the spring, summer, and fall; then, during the winter, they hug the Lowcountry’s coastline and barrier islands, which offer a humid, cool climate not so different from the oyamel fir forests of Mexico, and mate, laying eggs on Gulf Coast swallowwort, in addition to the usual aquatic milkweed, proving that the butterflies have another important host plant.

Back in the swamp, McCord weaves his way through chest-high grasses and squelching mud, his initially frosty manner melting away. He stops to point out banana spiders, an armadillo burrow, a question mark butterfly, a water snake. At one point, he mimics a warbler’s trill so well that it comes to scrutinize him from a few branches away. “I have an ear for sounds,” he says, waving off my astonishment. “I sing in my church choir.” We continue, step by laborious step, until he looks into the distance and cries, “And I see a monarch!”

At seventy-one, McCord is lean and wiry and moves awfully fast. I bumble along in his wake; while my thirty-year-old self fights for air in the humid oven of the swamp, he wields the long handle of a wide-mouthed net, whipping it expertly through the air to snag the first monarch of the day. He slips the butterfly into a specially designed wax envelope and tucks it into the cool darkness of his vest pocket. It’s not time to affix the tagging sticker yet; there are other butterflies here to be caught. He darts through the swamp, briefly safeguarding the body of one monarch softly between his lips while pursuing another. “Sometimes I don’t have time to put them in an envelope,” he explains, “and their wings are so sensitive I don’t want to be handling them.” A grin steals across his face. “And I know I won’t bite down, because these suckers are poisonous.”

Seeing monarchs float through this secret, inhospitable world is almost a mystical experience—or would be, if the sun weren’t steaming me in my waders and I hadn’t run out of drinking water and I hadn’t twice hit a hidden cypress knee and pitched forward on my face. As we approach our fifth hour in the swamp, we’ve caught some twenty monarchs, and the seemingly indefatigable McCord has finally begun to flag. “This is one of those days where I’m happiest when I’m done,” he admits. “And there’s another doggone monarch!” Off he goes. On other days, at friendlier locations, he tells me, he’s captured more than two hundred.

When I press him on why he dons camouflage and goes out at least twice a week in often oppressive conditions to tag, McCord just shrugs. “I have a passion for monarchs,” he says. “I know that I’m doing something that nobody else is doing.” And even though the species is one of the planet’s best-known insects, “they’ve probably been using these swamps for centuries, right under our noses. There is still so much to learn.”

While McCord believes that these monarch populations along the Eastern Seaboard are relatively stable, understanding their movements, habitat usage, and behavior could help conserve them in the future. Range-wide, the butterflies face an ever-growing list of challenges; their population has declined by 85 percent in the last two decades due to the likes of fatal pesticides, habitat loss, climate change, and the proliferation of non-native tropical milkweed, a popular yard plant that blooms at the wrong times of year and confounds properly timed reproduction.

Next, he and Kendrick hope to piece together whether some of the monarchs overwintering in the Lowcountry arrive from other states; if those monarchs are the ones living in the swamps the rest of the year; and if a larger migration of monarchs is occurring up and down the Atlantic Seaboard. Currently, the SCDNR lab is running tests on butterfly leg clippings, to eventually determine if the overwintering butterflies are genetically distinct from those that migrate to Mexico.

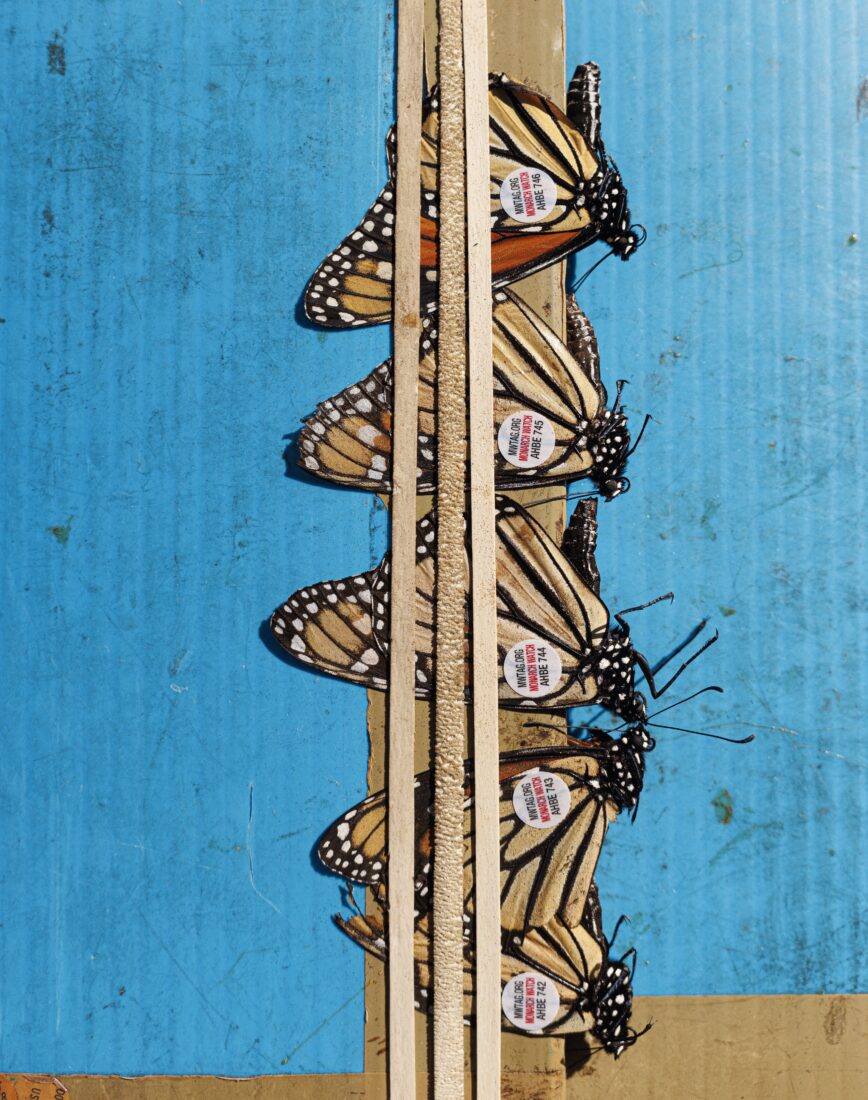

After each session in the field, McCord undertakes what feels like a ritual: He carefully transfers each butterfly to a clever board he designed on which he gently pins its wings with rubber bands. He records the insect’s length, sex, and wing condition before pressing a tiny circular sticker sporting a unique code on the outside of a wing. He has done this, to date, 53,630 times.

McCord then sets the butterflies free, and they flutter off the board, back toward the cypresses and tupelos of the swamp, traversing on paper-thin wings the miles we covered on foot. I watch them go, captivated, as humans have been for centuries. The Hopi culture believes monarchs bring abundance and health. Blackfoot people associate them with sleep and dreaming. Mexican folklore holds that they are the souls of the deceased, come to visit relatives in the world of the living. And yet here in the swamp, where each sticker on each delicate wing offers a window into a mysterious other world, science seems no less magical than legend.