Come fall in the Texas borderlands, forty-nine young Northern aplomado falcons—freshly fledged and not yet adorned with their dappled orange, white, and black adult plumage—will be honing their hunting skills and scoping out territory. The presence of the juvenile birds, born this past spring in the wild to wild parents on the state’s rugged grasslands and barrier islands, is nothing short of a miracle.

Historically, this medium-sized falcon patrolled the prairies of the Southwest and Mexico down into South America, using its impressive agility to hunt songbirds, reptiles, insects, and small mammals. The raptors were also so strikingly beautiful that Spanish explorers took them to Europe to serve as royal hunting falcons. But as time and colonization marched on in the New World, overgrazing, fire suppression, and invasive species degraded and destroyed the aplomado’s grassland habitat. By the 1950s, the now-banned pesticide DDT dealt the final blow, blinking out the bird completely in the United States.

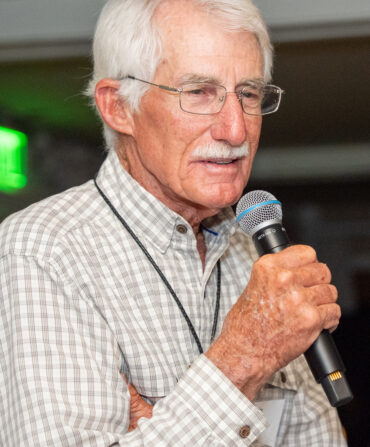

That’s where the Peregrine Fund, a nonprofit focused on global raptor recovery, came in. “In 1988, I went down to Mexico, and we brought back ten wild birds to form a captive breeding stock,” recalls Brian Mutch, the fund’s aplomado program director. Those birds, along with seventeen acquired from other collections, would go on to produce nearly two thousand chicks. Once the colony was thriving, it was time to put birds back on the Texas landscape.

“People said we’d never breed them, and if we did, we’d never release them successfully,” Mutch says. “But falconers have used hacking for hundreds of years to prepare birds for the hunt. We just adapted it for conservation—and it worked.” To “hack,” the group takes a thirty-four-day-old falcon to a release site and puts it into a hack box—a secure tower with a mesh front—and slips food in unseen twice a day for a week, mimicking a parent. In time, the caretakers open the door so the bird can step out, test its wings, and eventually fly.

Since the eighties, the Peregrine Fund has hacked 1,622 aplomados in South and West Texas. But the new population’s real challenge quickly became clear: quality habitat. “The birds are the easy part,” says Paul Juergens, the Peregrine Fund’s vice president of conservation for domestic programs. “We realized early on that we weren’t going to get this done on public land.” So the nonprofit—with the help of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, which agreed to mitigate the risk if landowners invited the endangered species onto their land—got to work bringing on board a seemingly unlikely ally: Texas ranchers.

Today, more than thirty ranches, including the 825,000-acre King Ranch, partner in the effort by allowing Peregrine Fund biologists to release aplomados on their land and return to band and monitor them. Some ranchers also get habitat up to snuff by conducting burns and removing invasive species. This fall, the nonprofit is improving public lands as well, ousting invasive mesquite and huisache at such sites as Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge to maintain the falcon’s prairie habitat.

Twenty-six aplomado breeding pairs now grace Texas, a number the team hopes will grow as it restores habitat and recruits ranchers. “That you can pull nestlings from trees in Mexico, transport them to the U.S., later captive breed them, and create a population that didn’t exist for fifty years is pretty crazy,” Juergens says. “The commitment is remarkable, and the program has as much momentum as ever to keep getting these birds back up in the skies.”