In 1951, an artist and angler named John Atherton published a quiet and exquisite little book entitled The Fly and the Fish. Atherton, whose paintings were already part of the permanent collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and who, like his friend Norman Rockwell, had gained broader renown for illustrating Saturday Evening Post covers, graced this miscellany—part memoir, part fly fishing manual, part oilskin philosophical treatise—with an array of sketches that stood as visual valentines to the fishing and fish he loved.

Photo: Courtesy of the American Museum of Fly Fishing

Stream Queen

Maxine Atherton on the Miramichi in the 1940’s.The book’s most graceful valentine, however, comes in a late chapter in which Atherton recounts a day on the Neversink River in Upstate New York. After spending a futile hour trying to deceive a big brown trout into taking a fly, Atherton had just given up when his wife, Maxine, or Max as she preferred, waded out to try for him. “Secure in the knowledge that if I could not get him after such long effort, she could not, I started off up the stream,” Atherton wrote. “I had gone but a few steps when I heard her reel screech and turned to see the fish slash madly across the pool. He had taken her second cast and thus two more males had underestimated the power of a woman.”

Photo: Margaret Houston

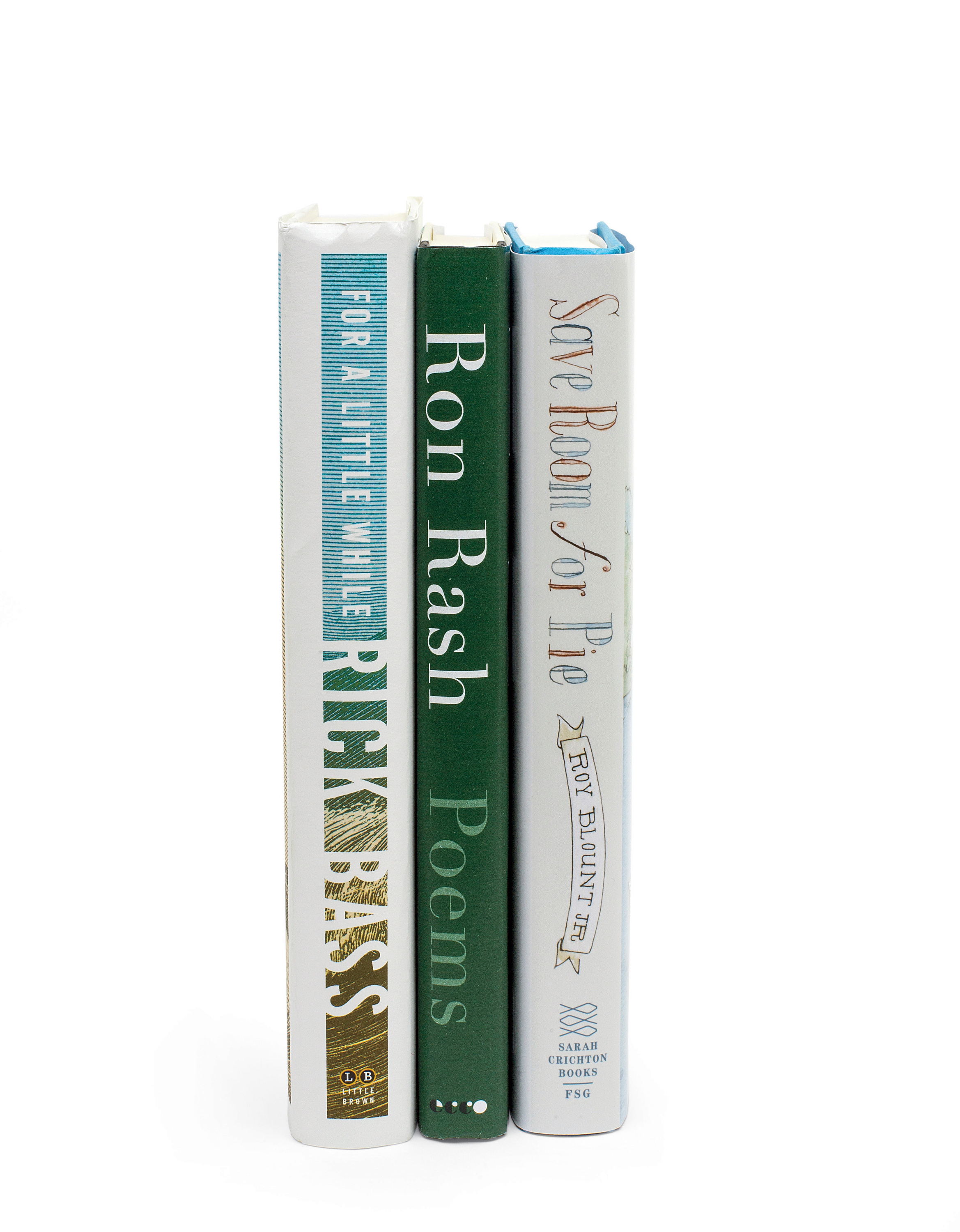

The Fly Fisher and the River

Skyhorse, $32

Sixty-five years later comes Max’s reply to that sly valentine. Mrs. Atherton’s The Fly Fisher and the River is a love letter to her husband, to fly fishing, to traveling, and to a life that she squeezed straight to the pips. Max Atherton died in 1997, at the age of ninety-three. She left behind a rubber-band-wrapped roll of manuscript pages that her granddaughter, Catherine Varchaver, eventually honed into this winsome yet powerful memoir, which Skyhorse Publishing is releasing in conjunction with a reissue of The Fly and the Fish.

Max organized her book, as she did her life, around rivers, and each chapter drops us streamside with her in Maine, France, Norway, Spain, Canada’s Arctic, plus a whole lot of in-between water. We meet her as a small child, accompanying her father to a trout stream in California’s Eastern Sierra (the dimpled water from feeding trout, he told her, meant the stream was smiling), and when we part ways with her, as “an outspoken, seventy-something fly fisherwoman,” she’s receiving a custom-designed graphite rod from the baseball and angling legend Ted Williams, her fishing-camp neighbor on the Miramichi River in New Brunswick, Canada. The only time the fishing ever recedes into the background is during her art-school days in Jazz Age San Francisco—but it comes shooting back to the foreground when she meets John Atherton, who proposed to her the very moment she divulged her affection for fishing. A quarter century’s worth of fish stories—or love stories, take your pick—follow.

John and Max’s love story, however, ends less than halfway through the book (and about halfway through Max’s life): The year after The Fly and the Fish was published, when he was fifty-two years old, John Atherton suffered a fatal heart attack moments after landing a twenty-five-pound salmon on the Miramichi. On the other side of that grief, however, Max channeled her passion into fishing, for which she traveled widely and rigorously—while fishing the Nansa River in Spain she was stalked by armed guards of the dictator Francisco Franco—during an era when being an itinerant solo fisherwoman was taking eccentricity to wondrous new heights. If Max Atherton hadn’t existed, the fish-minded novelists Jim Harrison and Thomas McGuane might’ve invented her. “Well into her eighties, my grandmother drove the 2,100 miles between New Brunswick, Canada, and her then home in the Florida Keys,” notes Varchaver in her foreword. “She had a constantly shifting array of houses and fishing camps, like the octogenarian equivalent of a carefree surfer chasing the next big wave.”

Photo: Margaret Houston

The Fly and the Fish

Skyhorse, $32

She’s the best kind of fly fishing raconteur: reverent without being pious, devoid of braggadocio, and aware till the end that out in nature we are always students, never experts. She’s also crotchety fun: “When we came to a little waterfall—low but fierce—the head guide motioned for me to get out of the canoe…and wait for them at the bottom of the waterfall,” she writes of a salmon expedition to Quebec, when she was already a grandmother. “Having been told that shooting over the low waterfall in a canoe was great fun, I refused to get out; but he paddled to shore and pulled me out.”

Taken together, these two books—which belong, stacked side by side, on every angler’s shelf—lend proof to what the French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry once wrote: that “love does not consist in gazing at each other, but in looking outward together in the same direction.” For the Athertons, together and apart, that gaze was always toward the smiling water.