There’s an ugly May storm turning the sky ten shades of blue, but a team of biologists is slugging down a tidal creek in the South Carolina marsh with a seining net, Converses laced tight against the sucking mud. They’re hoping not to get sliced by oyster shells or struck by lightning as they search for diamondback terrapins, an ever-rarer marsh turtle that is the subject of a long-running study here on Kiawah Island.

But before much of anything gets caught in the net dragging along the creek bottom, the skies open up in earnest. Rain sheets down as the biologists scramble onto three waiting boats, one of which proceeds to fill with water, causing its human cargo to abandon ship and splash headlong back into the marsh. “Our jobs would be easy,” somebody muses afterwards as we stand sopping wet on the dock, “if we could control the weather and the tides.”

Diamondback terrapins are native to the coastal tidal marshes all along the East Coast from Massachusetts to Texas—the only turtle in the world evolved to exist in the in-between world of brackish water. Like sea turtles, they cry salty tears to purge excess sodium chloride. Their flat shells, muscled legs, and webbed feet give them purchase against currents and changing tides. Aesthetically, they’re as stunning as they are variable, coming in shades of swirling olive greens, creams, blacks, and speckled slate grays, sometimes punctuated by sudden strokes of orange. Though small, terrapins play an outsize role in marsh stability by controlling populations of grass-munching periwinkle and mud snails. Unchecked, the snails eat down the cordgrass of the marsh, unmooring it and leaving it susceptible to erosion and the looming threat of sea level rise. They exhibit what science calls high site fidelity—meaning they have a strong sense of place and can spend their entire lives in the same creeks.

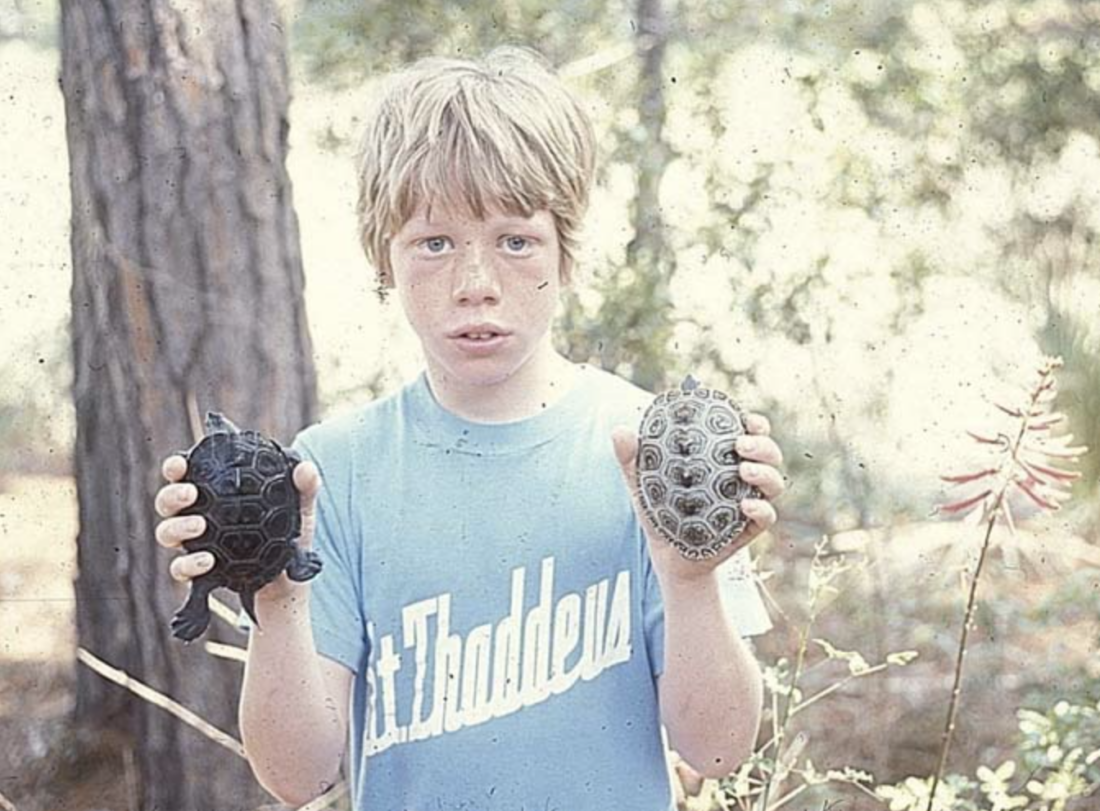

In 1983, University of Georgia professor emeritus, researcher, author, and all-around Southern herpetology legend Whit Gibbons had the idea for the Kiawah Island study when his son pulled two terrapins out of a crab trap. Soon after, he and his family—including his grandson, Parker, who still works on the study today—started hauling a fifty-foot seine down the creeks to turn up terrapins (and pretty much everything else underwater), picking out bycatch like mantis shrimp, small sharks, crabs, and fish. Graduate students and other partners got involved, among them the Charleston-based Turtle Survival Alliance. Today, Kristen Cecala, a herpetologist at Sewanee: the University of the South who has worked with Gibbons for decades, runs the project. To date, their annual surveys have resulted in the catch and release of 1,800 individual terrapins. As datasets go, it’s a valuable one—no other study of this species has run so long or has more potential to inform conservation efforts for a creature that’s beset by threats from all sides.

Despite the storm’s interruption of the sampling, which can only take place at low tide when the terrapins are active, there’s still yesterday’s yield of seven turtles waiting to be processed. Joined by Cris Hagen of the Turtle Survival Alliance, who has attended the survey every year since 2006, Cecala and Gibbons squint down at the first subject to determine if he has been caught before—information betrayed by a unique pattern of notches made in the shell upon initial capture.

“I feel like I know this one,” Cecala says, scrolling through the extensive database as Hagen calls out the pattern. She nods; he first appeared in 2013. “Eleven years since we last saw him,” remarks Gibbons. “Sometimes we’ll catch ones we haven’t seen in twenty or thirty years.” Of these seven, five are recaptures and two are new, and their weights, measurements, and markings augment the database.

The story it tells is not encouraging. Kiawah’s Terrapin Creek, named for its bounty of this very reptile, yielded its last turtle in 2009. In nearby Oyster Creek, the team last pulled up a terrapin in 2016. Of the five creeks surveyed since the beginning of the study, only two consistently harbor the species today. Overall, the researchers catch only 10 percent of what they did in the nineties; a creek that used to harbor sixty terrapins now might just hold six or seven.

The decline has its roots in a long history of exploitation. In the nineteenth century, diamondback terrapins were hauled in by the thousands to star in sherry-laced turtle soup, and commercial harvest wasn’t banned in South Carolina or other states until the early 2000s. Even with that particular threat eliminated, the data from Kiawah identifies two other major headwinds: coastal development that leads to habitat loss and car strikes, and accidental drowning in blue crab traps. During nesting season, which runs from May through July, female terrapins clamber up above the high tide line to nest, putting them directly in traffic to places like Kiawah. “When you see causeways to and on barrier islands, they are built on the salt marsh itself,” Cecala explains. “That puts most any road in potential terrapin nesting area.” Thousands are run over every season across their range—an especially grievous loss since females can live more than thirty years and lay eggs every year.

Meanwhile, a single crab trap can claim scores of terrapin lives; one pulled up in South Carolina held nearly a hundred drowned turtles inside. “Imagine a turtle that might be decades old, that has survived hurricanes, predators, and everything out here, only to get hit by a car or drown in a crab trap that should have had an excluder device,” Gibbons says. “It’s a tragedy.”

But work is being done on both of those fronts. Data from Kiawah has helped prove the effectiveness of bycatch reduction devices—little plastic rectangles attached to the entrance of crab traps to keep terrapins out—and last year, Florida started requiring them for the recreational blue crab fishery. During nesting season, terrapin crossing signs go up on coastal drives in Georgia and other states. Given all the threats, an effort to list the turtle as federally threatened or endangered is also brewing. And the study on Kiawah informs it all: The data has yielded some twenty-five scientific papers and counting, on topics ranging from food sources to hatchling behavior to a terrapin’s ability to recover from an injury.

Back on Kiawah, the seven captured terrapins paddle around shallow plastic bins, bumping into one another, not showing any signs of shyness even when scooped up for close examination. Tomorrow, they’ll go back out into the same winding channels of their brackish homes where they were caught. “Most people don’t even know terrapins are out here,” Gibbons says, balancing an olive green male on his fingertips. “But they are the charm of the marsh.”

Lindsey Liles joined Garden & Gun in 2020 after completing a master’s in literature in Scotland and a Fulbright grant in Brazil. The Arkansas native is G&G’s digital reporter, covering all aspects of the South, and she especially enjoys putting her biology background to use by writing about wildlife and conservation. She lives on Johns Island, South Carolina.