The Johnny Appleseed of Southern cider is a woman named Diane Flynt, who grows around a thousand heirloom apple trees on a farm in southwestern Virginia.

From 1997 to 2017, Flynt’s Foggy Ridge Cider made some of the best-tasting ciders in the country. Working with dozens of apple varieties, Flynt helped reestablish the drink as a regional craft on par with bourbon or beer, inspiring a generation of Southern cidermakers. Now semi-retired, she sells apples to some of her successors, including Ciders from Mars in Staunton, Virginia; Troddenvale in Warm Springs, Virginia; and James Creek Cider House in Cameron, North Carolina.

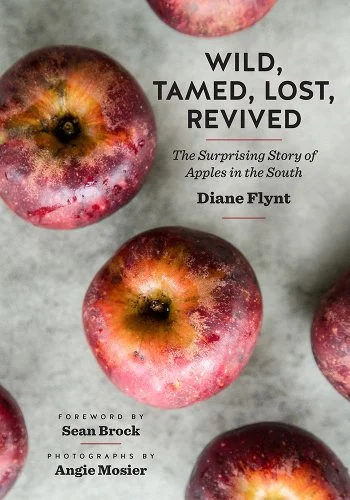

This fall, Flynt is sharing her knowledge in the definitive Wild, Tamed, Lost, Revived: The Surprising Story of Apples in the South. The book is part history, part botanical reference, and part memoir, chronicling the cidermaker’s own journey and experiences in the orchard.

For three hundred years, Flynt writes, the South grew a bounty of apples—more than two thousand varieties. Then, in about fifty years, as apples became more commercialized, that number dropped to fewer than a hundred. Alongside more common apples, the book spotlights varieties that have been lost or nearly lost to history, like Virginia’s missing Taliaferro, which made “the finest cyder” Thomas Jefferson ever drank, and North Carolina’s Junaluska, an apple with roots in Cherokee history that was thought to be extinct before a fruit detective recovered it in 2001.

“I wrote this book because I think it’s important for us to notice the world around us,” Flynt says. “There is value in the close observation of the natural world that goes beyond farming and gardening.”

With that in mind, we asked her to share five essential Southern apples worth seeking out whether you’re thinking about planting an orchard or just interested in Southern flavors, past and present. These apples are generally grown by smaller growers, so check your local farmers’ market or u-pick orchard for these varieties. And for a few standout Southern apple orchards to visit, Flynt recommends Albemarle Ciderworks in Virginia, the Southern Heritage Apple Orchard at Horne Creek Farm in North Carolina, and Mercier Orchards in Georgia.

Winesap

“Historically, no other apple even comes close to being as popular in the South as the Winesap,” wrote the late Lee Calhoun, a North Carolina apple grower and scholar whose archives Flynt has been organizing. The sweet-tart Winesap, a colonial apple still found in many orchards, is good for both juicing and snacking. “It has what Southerners call a twang,” Flynt says. “We like that. We like vinegar on our beans, sauerkraut, sour corn.”

Limbertwig

The name “Limbertwig” refers to a family of Appalachian apples, commonly associated with Tennessee and Kentucky. The late Baptist preacher Henry Morton, another icon among Southern apple growers, grew dozens of varieties on his property in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, some recovered from abandoned farmsteads in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. “The varieties all have their own particular flavors, but they have a distinctive Limbertwig flavor too,” Flynt says. “It’s a little spicy, and rich.”

Grimes Golden

An ancestor of the better known Golden Delicious, the Grimes is likely native to West Virginia, but nineteenth-century growers and distributors shipped it as far south as New Orleans via the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. “I think it’s prettier than the Golden Delicious,” Flynt says. “It’s a little lopsided, but it has a beautiful, rosy sun-kissed cheek.” It has a mild flavor, and it falls apart easily when cooked, making a “wonderful” applesauce and a rich apple pie. “No one could not like a Grimes Golden,” Flynt says.

Arkansas Black

The Arkansas Black isn’t quite black, but its plum-colored skin sets it apart. “You can shine it on your shirttail and it just gleams,” Flynt says. This isn’t an apple that you want to eat right off the tree. It gets better in the months after its October or November harvest. “It’s very hard when you pick it, and the flesh is white,” Flynt says. “After about a month, the flesh mellows and turns ivory-colored—the color of old piano keys. It smells so good in the cellar.” It will keep until April or May in a cool cellar or a refrigerator.

Yates

The Yates is what Flynt calls a “Deep South apple,” native to Georgia and tolerant of a warmer climate. “It persisted even when many apples went away,” Flynt says, for the same practical reasons it was a popular farm apple in the nineteenth century—because it grows well, it tastes good, and the apples last a long time in storage. It’s also a smaller apple, which Flynt prefers. “One reason why some people don’t like supermarket apples is that they’re so big, and you’re eating the same bite again and again and again. I think that a six-bite apple is just about the perfect size.”

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with Bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book. All books are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.