At 9:52 on a muggy July night, our first bat flies into the ghostly filaments of a net suspended high in the air. It’s a young female Seminole: petite, the color of mahogany, fluffy, snub-nosed, and emitting a click that would be as loud as a freight train, if only we could hear it.

Seminoles are one of thirteen bat species that have been found in Beaufort County, South Carolina, and one of nine documented in the Palmetto Bluff resort and residential community there. Most of the property’s twenty thousand acres of tidal creeks, marshes, and forests currently remain undeveloped, and the Palmetto Bluff Conservancy team of six protects it all, overseeing on-site archaeology, history, environmental outreach, and research crucial to the future of bats, whose 1,400-plus species keep the world’s ecosystems going. They are key seed dispersers and pollinators—more than three hundred fruits depend on them, as does agave. One study calculated that insectivorous bats save the United States agriculture industry alone an annual $23 billion in pesticides.

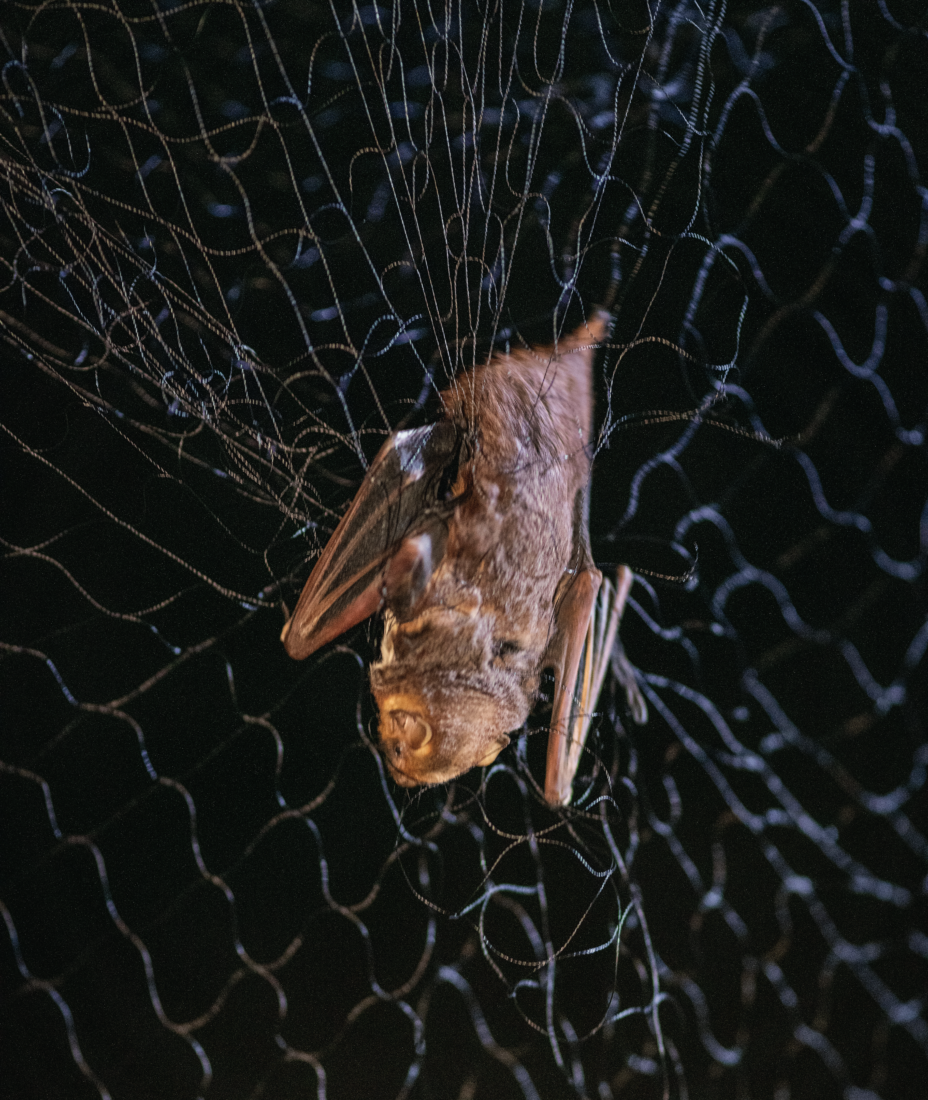

Lydia Moore, the Conservancy’s bat biologist, lowers the mist net we’d erected before the light faded. Nearly invisible and more than twenty feet tall, it and two others stretch across a wooded corridor where bats wheel and dart while foraging for insects among the saw palmettos, hickories, and pines. With deft, gloved fingers, Moore extricates the bat’s back end, then spreads a wing to unhook its thumb from the net. Once she secures the tiny mammal in a brown paper bag, the team records its data, including species, sex, and weight, and tags it with a numbered aluminum band on its forearm. Moore then launches the subject back into the darkness. She and bat biologist Jason Robinson capture these bats to study roosting ecology, habitat usage, and the role this area could play in combating white-nose syndrome. The fast-spreading fungal disease, first detected in 2006 in New York, killed more than six million bats within the first six years of its hitting North America, and has since spread across the continent, giving new urgency to this kind of research.

A 2016 discovery at Palmetto Bluff heightened that urgency: Robinson caught a northern long-eared while netting on a November night. “That bat had me questioning my identification skills,” he recalls. “The more I looked at it, the more excited I got.” White-nose syndrome has hit northern long-eared bats particularly hard; they have declined by 90 percent and are now listed as federally threatened. Until that moment, nobody thought they lived on the South Carolina coast.

“The coastal plain here has the potential to be a refuge for them,” says Jennifer Kindel, the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources bat biologist whose priority is netting for northern long-eareds throughout the state. White-nose syndrome causes bats to wake during winter hibernation, when food is scarce. In coastal areas, though, there are no caves where the fungus can thrive and spread from bat to bat; instead, bats roost in trees. Plus, winters don’t get cold enough to require long hibernation, and even if a bat does wake up, it’s likely to find insects. “Because of these different conditions, they have a chance here,” Moore says. But research is slow; as Robinson remarks, “You’ll catch two hundred other bats before you’ll catch one northern long-eared.”

Back at Palmetto Bluff, the night hours pass in seven-minute intervals, by which we scan the nets with flashlights for the dark shape of an entangled bat. We catch four species—Seminole, evening, big brown, and tricolored. We outfit an adult Seminole female with a transmitter, so we can track her to the tree she selects for daytime roosting—intel that offers a glimpse into bats’ secret lives and informs forest management. Bat biologists statewide are tackling other questions, too: How do expanding urban spaces affect bat behavior? How are tricolored bats faring against white-nose syndrome? Where exactly do northern long-eared bats roost in winter?

The next day, we follow the transmitter’s beeps to a pine tree, where Moore and Sam Holst, the Conservancy’s research fellow, use a scope and binoculars to scour the high reaches of the trunk and branches. “Every clump is a pine cone, except the one that’s a bat,” Holst says. After an hour, the Seminole remains hidden. They both shrug—bat research may frustrate, but “there’s so much we don’t know about even the most common species,” Holst explains. Moore adds, “Long-eareds used to be common in parts of their range; now they’re not. We are now scrambling to get basic information about them. We have to study common species while they’re still common—before something causes even more catastrophic population declines.”

And so they continue, into the dark year-round. On this second night of summer netting, just past 1:00 a.m., we check the nets a final time before packing up according to white-nose syndrome decontamination protocol—spraying the gear with disinfectant to kill any spores and changing our clothes in the humid night air. As we walk down the road by moonlight, a bat passes overhead, like a shadow.