When Paul Link opened his computer a few weeks ago and glanced at the extraordinarily long flight path of a female pintail duck whose tracking data had just arrived, he assumed she’d been harvested. As a waterfowl researcher for the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Link is accustomed to tracking pintails’ journeys to the eastern Dakotas and sometimes Canada. This one, though, went much, much farther. “When you see a random long line like that, you assume the worst,” he says. “You’re thinking, that bird is in a bag on a plane.”

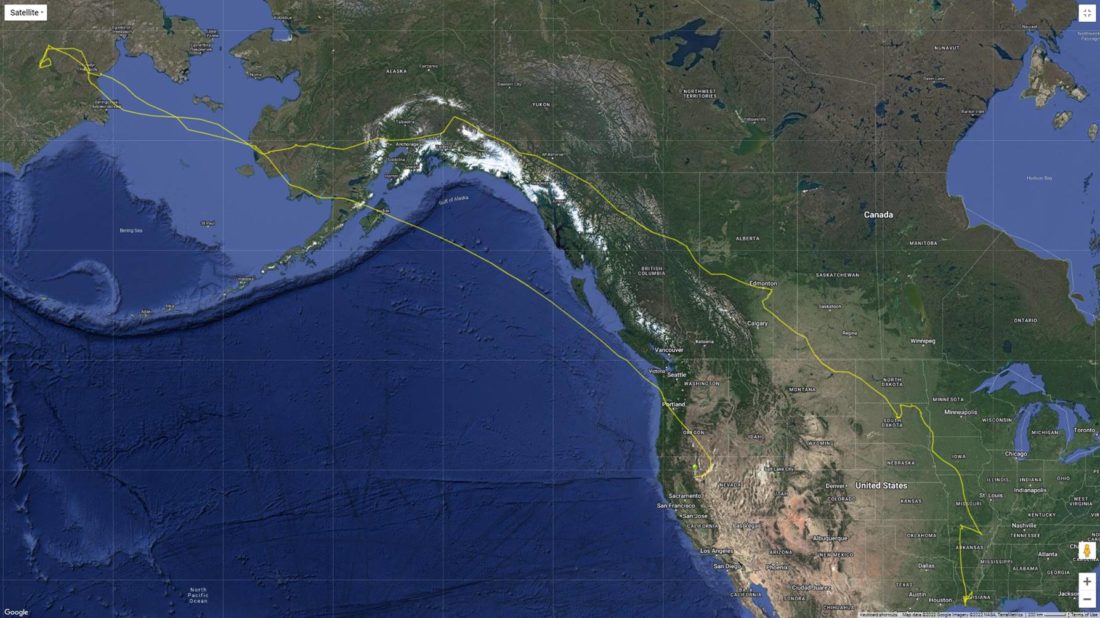

Then he downloaded the full dataset, which revealed the bird’s incredible ten-thousand-mile journey—made all on her own two wings. After leaving Louisiana in early March, the duck headed to the eastern Dakotas, to the Prairie Pothole Region, which stretches into Canada and sees the majority of pintail nesting and summering. But then she went offline for six months. “She finally hit service again on a state penitentiary campus in Northern California, of all places,” Link says. Between, she’d flown across northwestern Canada, passed through Alaska, crossed the Bering Sea, and arrived in Russia in May, becoming the first pintail Link—or anyone else—has ever seen cruising to a new continent from down South.

The monster migration was discovered thanks to Link and his team, who attached thirty transmitters to female pintails last winter as part of an ongoing study. Some of the transmitters, including the one attached to this bird, were lightweight, solar-powered, and fixed to the bird by a small piercing on the back; others were more traditional devices resembling miniature backpacks. Advancing technology like these transmitters enables researchers to better study the animals and, as in this case, reveal what we still have to learn. “It’s crazy to think that this bird passed through my hands and then went all the way to Russia,” Link says, “and to imagine all that she’s seen and survived: the storms, the blizzards, the ice; hunters, wolverines, foxes.”

He’s not sure why this duck chose to continue to Russia instead of staying in the Prairie Pothole Region. “Waterfowl science is one of the most advanced wildlife sciences there is. And still, after all these years, ducks are still mysterious, and they can still surprise us,” he says. “Something drove her to travel literally four thousand extra miles. Why?”

Even more interesting: Yesterday, another duck from those marked last winter reappeared online after completing a very similar journey—and even passed within a few hundred meters of the first duck, five weeks apart. Both, after molting and spending between fifty and seventy days flightless in the Russian Arctic, flew back to Alaska and then made incredible nonstop migrations of more than two thousand miles, one to California and the other to Montana.

The detailed data from their journeys is key to conserving pintails, whose numbers have been falling since the 1950s. Current population estimates ring in at 1.78 million birds—not far off the 1.75 million mark that would trigger the closing of hunting season on the species. Link hopes to better understand exactly where they go and how they rely on the habitats of each place they visit; the new transmitters include a a triaxial accelerometer (like a bubble level) that collects programmed bursts of behavioral data, meaning biologists can tell not only which habitat the bird is using but also what she is doing there, like flying, sleeping, preening, tipping, or dipping. That behavioral information—coupled with the location data—will inform future conservation efforts.

For now, Link’s Russia-going birds are approaching the completion of their annual cycle; come winter, they’ll be back down South, and Link hopes to see them at Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge again, where he tagged them. “Seeing these journeys really strengthens our land ethic and our sense of conservation stewardship,” he says. “These birds that have been to the Prairie Pothole Region, Alaska, or Russia…they’re planning on coming home to Louisiana, and they’re counting on us to have the habitat waiting for them.”