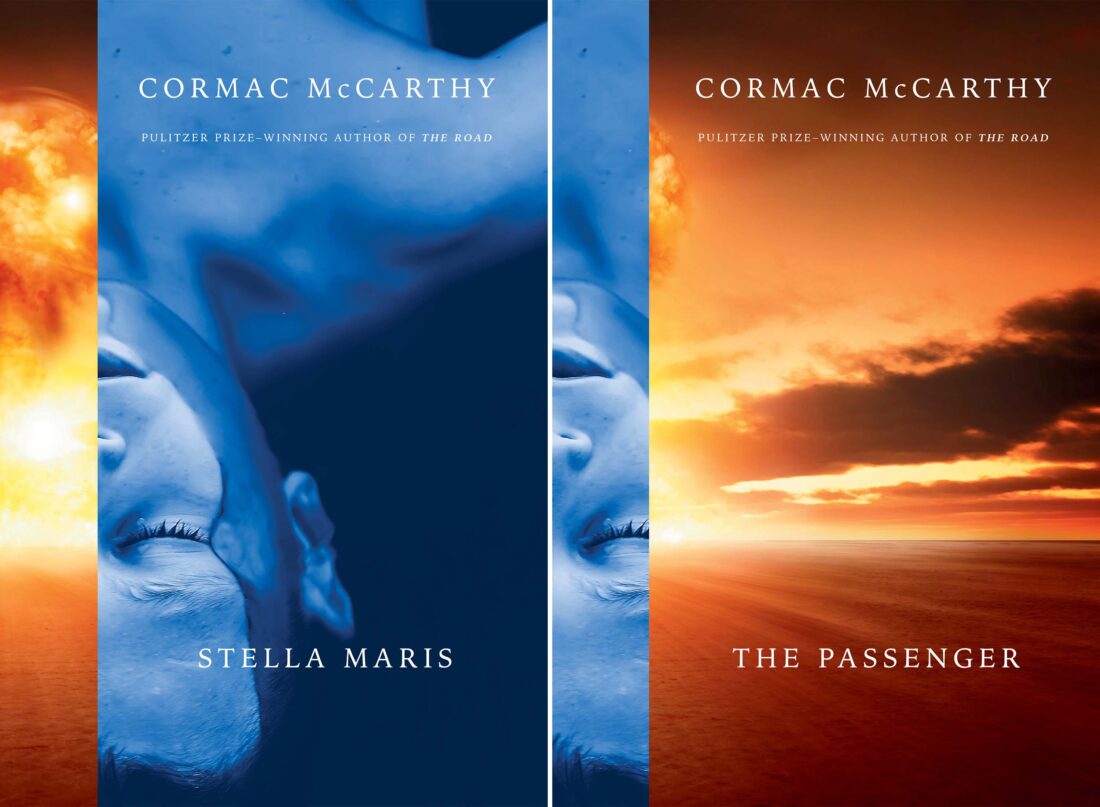

The author Cormac McCarthy grew up in Knoxville, Tennessee, but lived for decades in El Paso, Texas. When he died on June 13, 2023, at age eighty-nine, he left a literary legacy. A Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, many of his books were adapted for film, including The Road, All the Pretty Horses, and No Country for Old Men. Last year, sixteen years after releasing The Road, the notoriously private writer stunned and delighted fans when he published two novels. Here, Southern writers and the Garden & Gun staff reflect on McCarthy’s work and what his writing meant to them.

Pearl and James Lee Burke: I always wanted to meet Cormac McCarthy, but our trails never crossed. That said, he set the standard for the entirety of his career. There was no one better. His prose wasn’t simply prose; it was a form of unseen magic running out of his hand into the paper. He used language so well he did not need punctuation. There was an aura around every sentence, and inside the aura was a whisper that contained something you can’t see but you feel. Mr. McCarthy was an artist unto himself. He had the lyricism and the stormlike scenic vision of William Faulkner without being like William Faulkner. I think Ben Jonson would call him one for the ages, as Shakespeare was for the ages. And most of all, it’s obvious he was a purist and made no concessions. His art was a chalice, the kind that shines for eternity. I dearly wish I had met him. Our condolences to his family.

Aimee Nezhukumatathil: I’ll never forget the father reminding his son that they carry the fire in The Road. A reminder in the face of obstacles and pain and even evil, that they had to rise above, carry hope in their heart. I cry thinking about that boy asking his father at the end if the fire is real, if he can carry it. McCarthy had a way of forcing his characters to talk about the tough things rather than avoid them. The ending of that book might just well be the most beautiful last passage of a novel I’ve ever read.

S.A. Cosby: He was the rapturous, regal polemic Olde Testament voice from on high that wiped away the hypocrisy and the hagiography of the Olde South and forced us all to reckon with the traitorous rhetoric of what some call Southern Heritage. He was a truth sayer of the first order.

Russell Worth Parker: Cormac McCarthy made me think more deeply, by making me feel more deeply. He looked at humanity, and the landscapes upon which we exist, with an unflinching eye. But the simultaneously stark and rich worlds to which he took me made all the more vibrant the beauty of the one in which I read his words. And as a father, I can’t read this exchange in The Road without getting choked up: “What would you do if I died?… If you died I would want to die too…So you could be with me?… Yes. So I could be with you.”

Lee Durkee: In 1989 Tobias Wolff gave me a copy of an obscure novel called Blood Meridian that blew my mind, but my favorite McCarthy novel will always be The Crossing, a love story between two young brothers, Billy and Boyd, who travel into Mexico to find the bandits who killed their parents and stole the family horses. What I love about McCarthy’s least violent novel is the understated humor between the brothers. People forget how funny McCarthy was (is). I’ll always remember Billy trying to convince his younger brother Boyd that he was eating a cat taco.

David DiBenedetto, G&G editor in chief: As if I needed another reason to know the woman I was dating was my soulmate, she gave me a signed copy of No Country for Old Men for my birthday. We were engaged not too long after that. And remain happily ever after.

Elizabeth Florio, G&G digital editor: McCarthy was a well-established icon by the time I read The Road in 2006, and I made it to the end of that punctuation-averse hellscape out of sheer pride. Then, suddenly, I was sobbing on a public train. The Road taught me that some books are slow burns, and to this day when I’m struggling to get through a novel, I think of those subway tears and plow on.

Ace Atkins: An absolute craftsman and genius for sure. But McCarthy was also entertaining as hell. His books were filled with philosophy and existential dread while still working as brilliant stories packed with action. I dare anyone to try and read No Country for Old Men or The Road in more than one sitting. Like his hero Faulkner, some often forget how fun, scary, thrilling his novels can be.

CJ Lotz, G&G senior editor: Most of the time, I didn’t know what he meant exactly. I just thought the rhythms in his writing were beautiful. While reading All the Pretty Horses and Blood Meridian as a college kid and wannabe editor, I started underlining words I didn’t know. Then I looked them up and made a Word document, a scrappy dictionary of terms McCarthy dropped into my consciousness. How did he pick precisely the right word?

Remuda: the herd of horses from which ranch hands select their mounts

Scree: a sloping mass of loose rocks at the base of a cliff

Scapegrace: a wild and reckless person

Barrows: a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves

Legatees: someone to whom a legacy is left

Justin Heckert: He’s famous for his portraits of the Southwest, but I’ve always been more drawn to Cormac McCarthy’s descriptions of Appalachia and rural America. The junkyards and the dilapidated homes, the graveyards and rusted cars. Troubled characters walking barefoot on back roads, often bloodied, to nowhere good. Child of God is one of my favorite books. Reading it the first time was like being back in Crump, Missouri, as a child. That’s where my mother grew up, writing poetry about misfit characters passing on the dirt road in front of her, writing about graveyards of her own. Residents there, like in McCarthy’s dialogue, who knew each other and spoke in mottled language. Gravel roads and NO TRESPASSING signs, piles of leaves burning in vacant fields. Before Tuesday’s news, I’d randomly been on a McCarthy kick all June, spending many hours during evenings with him this month, in the ruined landscapes, in all the degradation, in the beautiful filth of the unending sentences.

Caroline Renee Henderson, G&G editorial intern: From All the Pretty Horses: “He stood at the window of the empty cafe and watched the activities in the square and he said that it was good that God kept the truths of life from the young as they were starting out or else they’d have no heart to start at all.” McCarthy wrote in a way that makes me mourn all of the bitter truths I have uncovered in my short life, and how there are so many more that I am thankful to be oblivious of.

Harrison Scott Key: Everything I know about parenting I learned from Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. I have to respect a man who refuses to be funny, though personally I find the apocalypse hilarious. This man’s epic career proves that country folks are the smartest people on the planet. I’ve been saying it for years.

Lisa Howorth: I was knocked out around 1970, before I moved to Mississippi, by the early Tennessee Cormac novels, particularly Outer Dark, which I suppose first made me aware of the thing “there are many Souths.” Later, although he was an incredible writer, I haven’t been in the cult—the later novels seemed a little mannered, maybe lacking the heart and humor of Faulkner, who has always been the apogee. But now I value Cormac hugely for bolstering the Faulkner lineage, and for the great inspiration he was to so many great writers like Larry Brown, who at the drop of a hat often quoted long passages from his books.

David Joy: Having spent a life with his work, R.I.P. feels like a missed philosophy. “How surely are the dead beyond death. Death is what the living carry with them. A state of dread, like some uncanny foretaste of a bitter memory. But the dead do not remember and nothingness is not a curse.” He laid this ground in Suttree, tested the extremes with Blood Meridian then felt out and solidified the walls over the remainder of what would become his oeuvre. Yet, there was seldom a hopelessness. “You have to carry the fire,” the father tells the son in The Road. McCarthy’s burned bright and left nothing unfinished. His body of work is complete. I can’t think of anything more an artist could hope to leave behind.

Taylor Brown: Cormac is one of our great winds. Though the man is gone, may his voice and word grow only stronger.