Chances are, you’ve never seen Florida’s official state animal in the wild—not even you rural Floridians. Florida panthers are stealthy creatures, despite their size, and do most of their prowling from dusk to dawn. More important, they’re profoundly scarce. The state’s best population estimates range from 120 to 230 panthers.

Twenty-five years ago, however, those sighting chances were close to nil, and the odds were looking strong that, within a decade or so, no one would ever again see a Florida panther in the wild, because there simply wouldn’t be any. Only a handful remained back then: twenty by one mid-1990s estimate, six by another, both numbers absurdly dire. The Florida panther’s cousins had long since been wiped out in other Eastern states. Only the human-resistant ferocity of Florida’s interior—“nothing down here,” as Jack Kerouac wrote, “but scorpions, lizards, vast spiders, mosquitoes, vast cockroaches & thorns in the grass”—had cushioned the panther from a similar fate. But the onrush of development was ending that cushion, paving the way—literally—for the panther’s end in the wild.

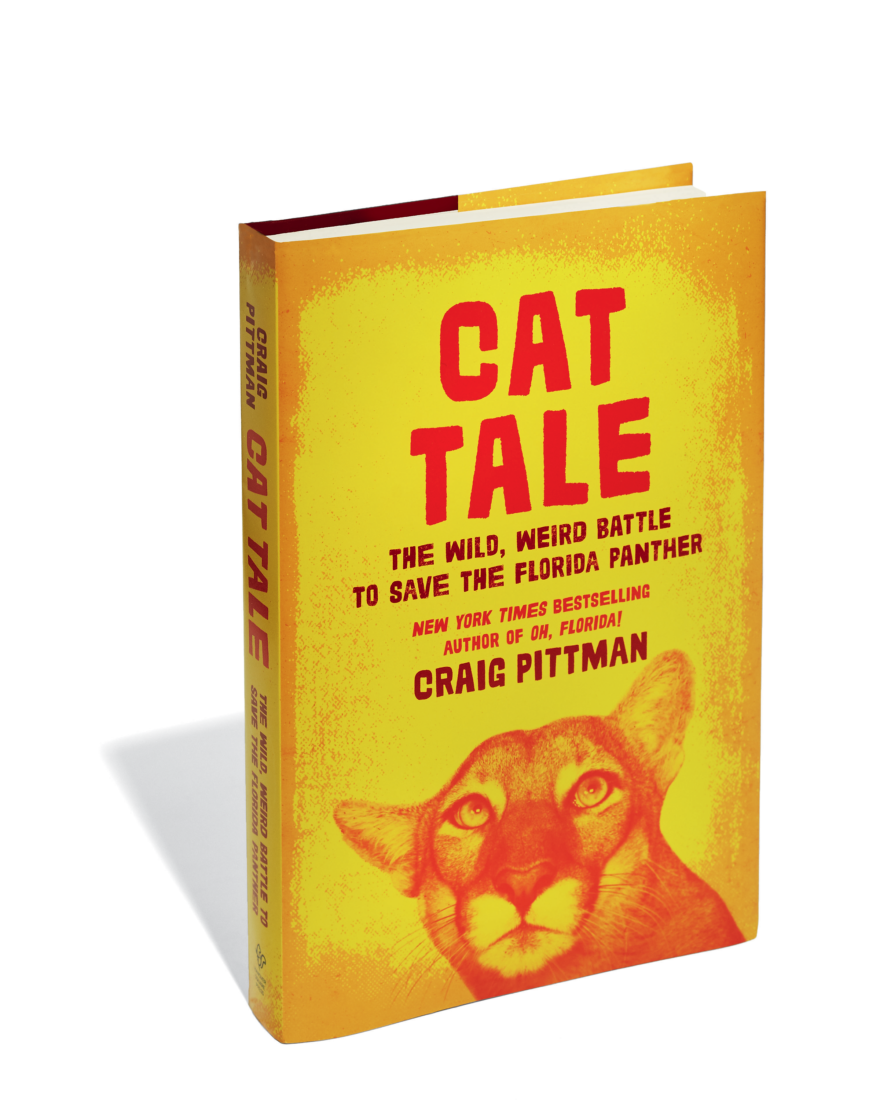

Craig Pittman’s Cat Tale: The Wild, Weird Battle to

Save the Florida Panther tells the story of how that didn’t happen. Environmental story lines that don’t end in gloom are their own kind of endangered species these days, which is just one of the pleasantly oddball aspects of Cat Tale. Pittman, a longtime Tampa Bay Times reporter, has written a ticktock account of how a band of scientists mounted a desperate rescue operation to pull the Florida panther back from almost certain extinction. It’s a punchy, riveting story—despite spanning decades and despite many of the pivotal struggles playing out on the bureaucratic level—that rouses and uplifts (for the dogged work of its central cast, and for the fragile success they achieved) while also infuriating and dismaying (for the man-made obstacles they faced, and for the degree of that fragility).

Scientists tend to make for dry copy, but this is Florida, where nothing is ever fully dry. So we have Roy McBride, a West Texas hunter for hire whose wolf-hunting skills were the inspiration for Cormac McCarthy’s The Crossing. McBride gave up killing cougars for sheep ranchers in order to track and tag them for scientists, and he became instrumental to Florida’s effort to save its panthers—a defector to the cause of conservation. But we also have David Maehr, a seemingly gung ho wildlife biologist who, as Pittman painstakingly documents, cut corners on his research and then used the shoddy results for a lucrative sideline “aiding builders and developers and mining companies that wanted to run a steamroller over state and federal regulatory agencies”: another kind of defector.

As with everything Florida, the deeper you go, the stranger it all gets. The panthers faced an array of existential threats: habitat loss; pollution; cars; and sometimes, from spooked or vindictive Floridians, bullets and arrows. But inbreeding, as one scientist discovered, might’ve been the most urgent threat, and addressing that proved key to the panthers’ comeback. The scientists’ “Hail Mary pass,” as Pittman characterizes it, was to import and release Texas cougars to freshen up the gene pool. This controversial “outbreeding” gambit succeeded, but as panther numbers increased, so too did nonchalance about—and sometimes opposition to—preserving their habitat. Hence another grave threat: greed. At one point—I think it was when a federal bureaucrat overrode biologists’ objections to a development by decreeing “Florida will be developed,” or maybe when opponents of panther relocation coined the idea that “extinction is God’s plan”—I imagined a panther mirroring the thoughts of a character in a Lauren Groff story: “Of all the places in the world, she belongs in Florida. How dispiriting to learn this of herself.”

Yet big cats are more or less extinct in every other state east of the Mississippi; only Florida has them, because only Florida devoted itself to saving them. And suitably, Pittman closes Cat Tale on an optimistic note. But caution is warranted. To quote Jimmy Buffett: “If you take one look behind the shine / it doesn’t always gleam.” Of the state’s maybe two hundred panthers, more than a dozen have been flattened by cars so far this year. In August, state officials released trail-cam footage showing panthers with a mysterious affliction hobbling their ability to walk. The heroic effort to save the panther, thrillingly chronicled here, deserves an equally heroic commitment to ensuring its future.