Conservation

Hatching the South’s Rarest Fish

Tennessee biologists race to save the tiny, endangered—and stunningly beautiful—residents of our waters

In the crowded hatchery of Conservation Fisheries Inc. (CFI) in Knoxville, green nylon-yarn mopheads sway underwater in a tub, mimicking the vegetation where Barrens topminnows lay their eggs. Strings of white lights dip from the ceiling, switching on morning and evening for the Smoky madtom, which feeds by the pale light of dawn and dusk. A turkey baster sits on a shelf, ready to slurp up yellowcheek darter larvae as they hatch. And a cement mixer swirls water with gravel, which when clean will be returned to one of the 832 fish tanks here. “Welcome to our little mess,” J. R. Shute says.

In 1986—a time when river pollution ran rampant and conservation efforts focused on game fish—Shute and his business partner, Patrick Rakes, founded CFI to propagate the smallest, most endangered, and craziest-looking species of Southern fish you’ve never heard of. Today, they and a team of eight other self-identifying “fish people,” also known as aquatic biologists, spend all year catching, breeding, growing, and releasing thousands of fish, most no longer than a few inches, to boost fast-dwindling populations.

The Southeast boasts the most aquatic biodiversity in the temperate world—nearly 500 fish species, 270 mussel species, and hundreds of other freshwater denizens—thanks to ancient geology. During the Ice Age, glaciers didn’t reach the Appalachian Mountains, which sheltered fish as they evolved in hyperspecific habitats. Many of them are native to just one river system; some exist in a single stream. But now extinction threatens hundreds of species due to siltation, damming, pollution, and unpredictable weather patterns.

“People have no idea what is underwater here,” says Bo Baxter, a CFI biologist. “If they did, they’d want to protect it.” To do just that, the team members tote kayaks and snorkeling gear around the South to catch fish. They painstakingly count eggs. They grow almost the whole aquatic food chain to feed their subjects. They puzzle out how to replicate stream conditions in tanks. “They’ve done more to save the South’s rarest fishes than anyone else,” says Gary Peeples, of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, a partner in CFI’s efforts.

To date, CFI has propagated more than seventy species, and it’s raising funds to expand and upgrade the hatchery. “There are more species than we could ever help,” Shute admits, but the team isn’t giving up on the region’s spectacular biodiversity. “When you’re out there in the streams, with your head underwater, it feels like you’ve been let in on a secret.”

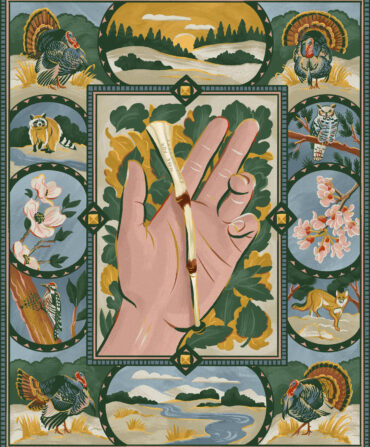

Illustration: Song Kang

1. Barrens Topminnow

Only three small original populations of this federally endangered fish remain in pockets of Tennessee’s Barrens Plateau, threatened by agricultural runoff and invasive mosquito fish. CFI propagates them for stocking and to create ark populations; to catch them, Rakes and Shute use binoculars to scan the water for the bright white stripe along their backs.

2. Boulder Darter

These endangered fish get their name from the moderate to fast-flowing rocky sections of the Elk River they call home in Tennessee and Alabama. Over fifteen years, CFI has released more than five thousand of them into Shoal Creek, a tributary of the Tennessee River near the Elk, and hopes to soon declare the population established.

3. Spring Pygmy Sunfish

Staff favorites because they’re just plain cute, these inch-long fish have a temperature-controlled room of their own at CFI, which keeps an ark population in case they go extinct in the one place they are found: Beaverdam Creek watershed, which drains into Wheeler Reservoir near Huntsville, Alabama.

4. Buck Darter

Native to the cool water of Kentucky’s Buck Creek watershed, Buck darters attach their eggs to the undersides of rocks, making them vulnerable to water polluted with silt from mining or development. CFI started propagating and releasing them in 2016, and last year the team observed some of the fish reproducing on their own.

5. Bluemask Darter

To catch bluemask darters, CFI biologists often have to lie on their stomachs in the tributary streams of the Caney Fork River system in central Tennessee with their heads ducked under the shallow water, nets at the ready.

6. Carolina Madtom

This dwarf catfish, listed as endangered last year, lives in North Carolina’s Tar and Neuse River systems. A male guards his nest fiercely; if he thinks a predator has breached his defenses, he’ll eat the eggs himself. At CFI, one male is so notorious for this behavior he has earned a nickname: Hannibal the Cannibal.

7. Banded Sculpin

Over millions of years, many mussels evolved elaborate lures to attract just one or two fish species to which their larvae could attach and travel to start new populations. If that fish disappears, so do its mussels. The banded sculpin hosts the slippershell mussel, and CFI, with the North Carolina Wildlife Resource Commission, releases them in the Cheoah River.

8. Roanoke Logperch

A breeding pair of Roanoke logperch carefully consider where to lay eggs, pointing with their noses to discuss sites. They live only in five disjunct areas in Virginia, and CFI is propagating them to expand their range back into North Carolina. “They are the king of the darters,” Baxter says. “They wear their fin like a crown.”

9. Tangerine Darter

“This is a fish that demands notice,” Shute says of the neon “river slick,” as it’s also known. They favor cool Southern Appalachian streams, and since 2003, CFI has tried to restore populations to Tennessee’s lower Pigeon River. “They’re a reminder that we are in the rain forest of the temperate world.”

10. Tennessee Dace

“Their color can change like that,” Shute says, snapping his fingers. The males streak brilliant red and yellow during breeding season in the Tennessee River system. In 2021, the Forest Service gave CFI a population to propagate for reintroduction into the Cherokee National Forest.