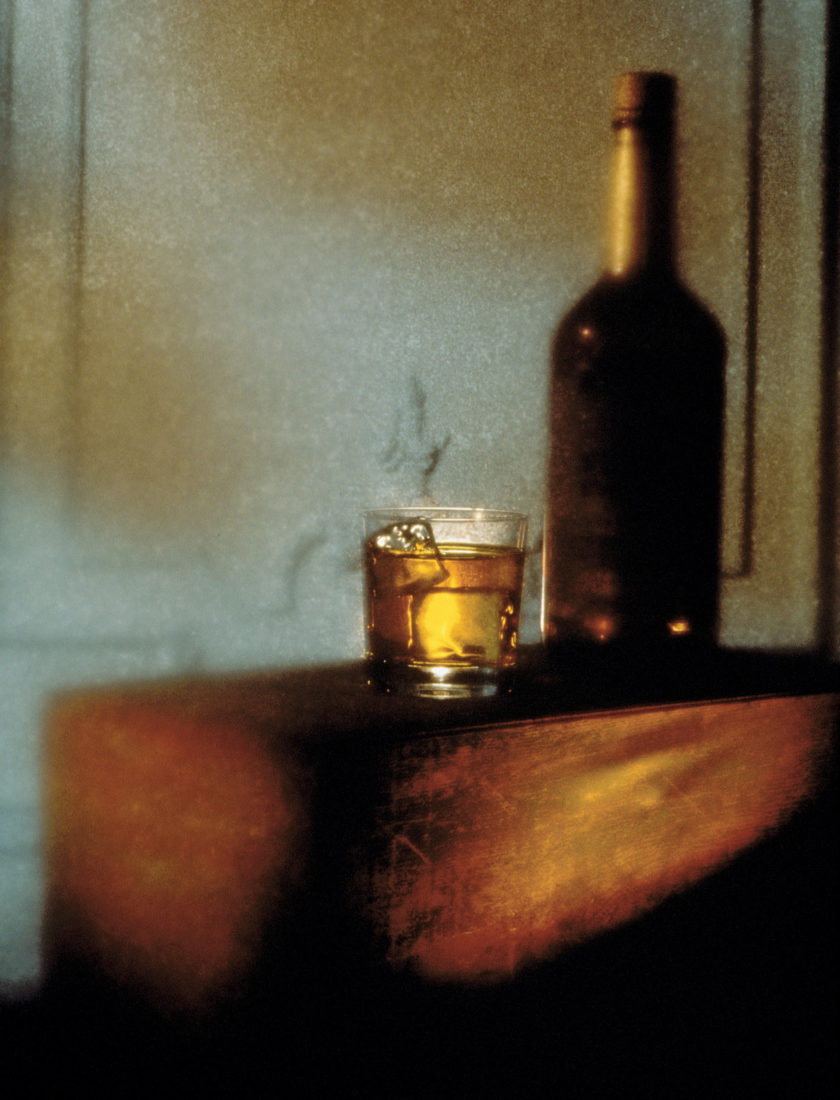

Drinks

Ode to Bourbon

Four writers’ sweet reflection on a sour mash

Photo: Michael Sean, Nonstock, Courtesy of Jupiterimages

Walker percy’s 1975 classic essay on bourbon praises the aesthetic of swilling that “little explosion of Kentucky U.S.A. sunshine … and the hot bosky bite of Tennessee summertime.” Per Percy, “Bourbon does for me what that piece of cake did for Proust.” It would be a challenge to find a Southerner without a good bourbon story. If it’s not your libation of choice, your father drank it, or your mother cooked with it, simply calling it whiskey, or your grandfather had a secret eggnog recipe calling for bourbon poured with a heavy hand. With this in mind, and drawing inspiration from Percy, G&G asked four writers to meditate on the matter and lend their voices to four modern-day odes to bourbon. Beloved humorist Roy Blount, Jr., raised in Georgia, author of the recently published Long Time Leaving: Dispatches from Up South, is a regular on National Public Radio’s “A Prairie Home Companion” and “Wait, Wait … Don’t Tell Me!” Acclaimed novelist Donna Tartt is a Mississippi native, now at work on her third novel from the quiet of rural Virginia. John T. Edge, dubbed the “Faulkner of Southern food” by the Miami Herald, is director of the Southern Foodways Alliance, an institution of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi. Chef John Currence is owner of the Oxford, Mississippi, restaurant and bar City Grocery, and is a frequent contributor to G&G, writing about hunting and culinary arts. For these writers, as well as the majority of Southerners, dating to the earliest settlers, this homegrown beverage has the ability to transcend the liquor cabinet into the spirit of the South.

TENNESSEE SIPPING WHISKEY

Getting to the bottom of a good bottle

by Roy Blount, Jr.

You should never drink whiskey alone, unless there’s nobody else around and you have research to do involving drinking whiskey —in this case, trying to get to the bottom of why I like whiskey so much. But not to the bottom of any of the three bottles involved in this research. If I were to reach bottle bottom and enlightenment simultaneously, or concurrently, I might not feel the same way about my conclusions, or even remember them, in the morning.

My research so far: a sip of Jack Daniel’s, a sip of Wild Turkey, and a sip of Bulleit Bourbon, which is new to me. They are all good. Plenty good enough. I like those single-malt scotches and special reserve bourbons, but unless somebody else is serving them, they cost too much for me to enjoy.

One thing about whiskey is, it has so many great names. Old Overholt, the Famous Grouse, Black Bush, Heaven Hill, Tullamore Dew. And let’s face it, it’s what they drink in cowboy movies. You don’t see white hats or black hats tossing back shots of vodka or rum or taking a bottle of Pinot Grigio to the table.

Usually, when I drink whiskey it’s Jack Daniel’s, Tennessee sipping whiskey. I just had a sip from the bottle, and it was good. But you know what Jack Daniel’s doesn’t have that Wild Turkey and this Bulleit Bourbon do? A cork. A cork is a great thing in a whiskey bottle for the pleasure of pulling it out. Let’s see if I can spell the sound: f-toong. That’s if you pull it straight out. If you give it a little twist as you pull it, there’s a squeak — no, a chirp, a tweet even — that drowns out the f and even the t. Interesting. That never really registered with me before. Sort of squeeoong.

A good thing about whiskey is that you can drink more of it than you can martinis. “Razor-blade soup” is what somebody once called a good dry martini, and I enjoy one (not flavored with chocolate or whatever — bleh!), but two of them is about a half of one too much for me. I can’t remember ever doing anything rousing or having any very interesting conversation after two martinis. On the other hand, I can have two or three whiskeys, occasionally (never more than six or seven nights a week), and get relaxed rather than poleaxed. I can even write. See? Drive, no, but there’s no way you can run over anybody while writing.

Maybe I should work up something to say when I take a sip, or, okay, a slug, of whiskey. In Easy Rider, Jack Nicholson says this: “NICK…NICK…NICK, ff ff, INDIANS!” That’s a little too elaborate for me. Not to mention ethnically insensitive. Here’s to everybody! Whoops! Or, no, this is more cowboy: Whoopee!

I like Wild Turkey, and this Bulleit isn’t at all bad, and, by the way, the Bulleit comes in a flask-shaped bottle that is pretty cool. Jack Daniel’s, however, is just eighty proof, whereas the Bulleit is ninety, and this Wild Turkey I have is — whoa — 101. So you can drink more of the Jack Daniel’s. How much more? Well, I never said I could drink and do percentages.

Love those corks, though. Too much. I’ve pulled them so many times now tonight, trying to decide which one has the better tone, that they’ve lost their music. Kinda sad. I’ve worn them down. They’re not tight anymore.

I am, though. Just to the point where I’m feeling sorry for corks and have forgotten what exactly I was researching. But I enjoyed it. Do I live near here?

EARLY TIMES IN MISSSSIPPI

A look at the spirit through the prism of the past

by Donna Tartt

Bourbon, for me, is a smell that goes all the way back to childhood and Christmas, the red-striped cocktail glasses at my grandmother’s house, grown-ups in corsages and wearing their best jewelry, everyone laughing, the very smell of warmth and gladness on the breath of people I loved. Even when I was tiny, I knew the sugary burn of its taste — in eggnog (of which I was allowed only a sip, once a year, in a painted cup from a doll’s tea set), in the whipped cream my mother used on pecan pies, and in the boozy butter cakes with cherries and walnuts that we ate at Christmas. My family never called it bourbon, they only called it whiskey, and until I was sixteen or seventeen I believed all whiskey was bourbon. Even in desserts, it had a dangerous, grown-up taste, a hazardous smolder I associated with Christmas fireworks—possibly because, as it was explained to me, the proof of whiskey had been determined in the old days with a lighted match and gunpowder. Gunpowder, soaked in any liquor at least fifty percent alcohol, will flash up and ignite (or, as I imagined, explode, with the thrilling Roman-candle smell that drifted over the yards in the old part of town, at Christmas time).

I grew up in a dry county. The liquor store—a shack, in a field, just across the line into Yalobusha County—was discreetly called “the package store” by even the roughest and most incorrigible lushes. Apart from the occasional bottle of rum—which ladies used “as flavoring” in bananas Foster and fruitcakes—bourbon was generally the only spirit that people had in the house, if they had anything. Beer was for hoodlums; gin was for Englishmen; wine was a rarity. When the adults of my childhood drank, they drank bourbon—Wild Turkey, Old Grand-Dad, Kentucky Tavern, Old Crow, even the names were a sort of poem — and they drank it not as a casual matter of the nightly cocktail, but only at parties or when they were ill or deeply distressed, so for me it was a sitting-up-late smell, the smell of gatherings and special occasions: of parties and hilarity but also of grief, emergencies, coughing and sickrooms, high fevers, lights burning late into the night. At my house, the bottle was kept under the bathroom sink, with the iodine and Band-Aids, like medicine.

Bourbon was what I drank on my first date with a boy, in the dark front seat of a Cadillac in winter, freezing to death in my silver-white evening dress. At school in New England, and in my early days in New York, I drank bourbon because I was homesick, and it smelled rich and warm like home. I’ve had some festive bourbons at Harry’s Bar in Paris — also at the Grand Hotel in Stockholm, where Faulkner drank more than a few bourbons before he went in to deliver his speech and accept his prize. But as I’ve grown older, bourbon has become so freighted with the past that it’s almost an unbearably sad drink: the smell of old men standing around after funerals. I almost never drink it now, for fear of being swamped by nostalgia. That particular dark sweetness reminds me too much now of lost friends, lost childhood, lost things in general. The last bottle of bourbon I can remember buying was years ago, during a sad autumn when I was living out in the country, in France: early October darks, vineyards in the rain and country roads littered with chestnut leaves, hunters’ gunshots echoing through the woods with a lonely pang of my Mississippi childhood, rain and more rain and gusty nights, early dinners in deserted rural cafes, and a melancholy walk home to bed. Before, in Paris, I’d been struck by all the bottles of Jack Daniel’s left as grave offerings in Père-Lachaise and Montmartre, sitting atop the tombs amid dank bouquets and piles of rotting leaves, and I was left wondering if bourbon had some distinct funereal whiff that made it a pleasing gift to the dead, or if bourbon drinkers were simply more apt to be disconsolate and roaming the graveyards in a foreign city—which seems the more likely possibility, since bourbon drinkers are some of the

saddest people I have ever known.

There are only twenty dry counties left in Mississippi. In the town where I grew up, there are now three liquor stores on the road to my old school, stocked with single-barrel bourbons unheard of when I was a kid. I can’t say what happened to the shack in Yalobusha County, Brown’s Package Store (or “Dr. Brown’s,” as it was picturesquely known to its customers), except that it is almost certainly gone now. With it has vanished — for better or worse — much of the secrecy and ritual that characterized bourbon-drinking when I was a child, that sense of the Jim Beam hidden in the glove compartment, the uncles passing the bottle around out on the back porch. (My friends and I, when we were children, used to stumble across those flat pint bottles squirreled away in the oddest places: in old suitcases, in toolboxes and flowerpots in neighbors’ garages, under beds and behind bathtubs, in the desk drawers of our parents’ employers, inside the back panel of an old console stereo specially altered for the purpose — perhaps most memorably, under the front seat of the school bus. Our bus driver, Mrs. Trotter, when confronted with the discovery, commented: “Even old Trott needs her a little pick-up now and then.”)

But along with the danger — the cocktails in the car on the way to the country club, the drunken midnight drives home from dances in the Delta — a lot of the magic has vanished, as well. Gone are the dizzy Christmas parties of my childhood, with firecrackers, candy and cake, and fragrant old gallants in high-waisted suits (some of whom, after one too many snorts, could be persuaded by a pleading child to do their imitation of Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer, or stand on their heads in the corner). Even now, the afterburn of those parties still glows fiercely in my vision, like the colored sparks that showered across my retinas long after the last fireworks had been shot, after the coats had been fetched and the last toddies had been downed and the guests — still talking loudly in the clear winter night — tromped out to their cars laden with presents, shouting their happy good-byes.

RESPECTING RESERVE

A whiskey drinker comes of age

by John T. Edge

When I was in my late twenties, living in Atlanta, my friend Nelson Ross taught me the value of better bourbon. But he did it in an ass-backward way.

Nelson was keen on Blanton’s, the first single-barrel bourbon. He liked the squat bottle. He liked the horse that pranced atop the stopper. And he liked the whiskey within, secure in the knowledge that his bottle was not filled from the spigot of a multinational’s sluice silo. Instead, Nelson’s bottle of Blanton’s was traceable to a single charred oak barrel that, when the distiller tapped the bung in preparation for a bottling run, bloomed with scents of toffee and fig—the scents, in short, of fine bourbon.

Problem was, Nelson only drank Blanton’s on special occasions. And on those special occasions he drank Blanton’s from eggcups—actual eggcups—fashioned out of pickled eggs, sold by his favorite barkeep.

The idea was almost ingenious: With a pocketknife, cut a pickled egg across the midsection. Scoop the yolk from each half, taking care not to tear the white. Pour a dram of bourbon in each cup and swirl to dislodge any clinging yolk matter. Fill the eggcups in the manner of shot glasses and gulp.

For the longest time, I associated good bourbon with a sulfurous back end. Truth is, in those days bourbon was nothing more than drunkard’s fuel. Blanton’s was wasted on my friends and me because, well, we were wasted when we drank it. Not freshmen-in-college wasted, but sufficiently addled by longnecks that, by the time someone pulled out a pocketknife, we couldn’t discern the difference between top shelf and bottom rung.

I’m now in my forties. And I still pitch a drunk now and again. But I don’t drink Blanton’s. Good as it may be, Blanton’s comes with too much olfactory baggage.

I’ve upgraded my liquor cabinet—and my china cabinet. Now when I reach for a better bourbon I pour a crystal rocks glass of twenty-year-old Pappy Van Winkle Family Reserve, the pride of Van Winkle men for three generations. After twenty summers in oak, Pappy, a wheated Kentucky whiskey, conjures a cognac gone country, which is to say the nose is soft, tobacco-sweet, almost floral, but the back end still kicks like a corn-fed mule.

No, I’m not going effete on you, Nelson. It’s just that I’ve come to respect bourbon as more than a mere buzz catalyst. I’ve come to appreciate the heft of a razor-lipped tumbler, sloshing with amber liquid. I’ve come to believe that—forgive me—while eggs and whiskey can mix, that doesn’t mean they should.

PROUD TO DRINK AMERICAN

Standing behind the spirit of the South

by John Currence

I grew up in New Orleans, a town of birthright drinkers where cocktail history is debated like sport and your drink choice is defining. By the age of twenty-two I considered myself light-years ahead of my North Carolina college friends, and had even chosen an unsung import as my poison—Jameson’s Irish Whiskey. Painfully, I believed I understood my choice and, worse, thought it made a profound statement about the torture that I, like James Joyce, was suffering in life. Hubris, as it turns out, comes with a price tag, a lesson I was force-fed at a Scottish pub called Saucy Mary’s, on the Isle of Skye, during the summer of 1988.

Little can match the humiliation of marching into a Scotsman’s pub and proudly ordering an Irish whiskey. I was, it turns out, just that dumb. What I learned from that night was that there is an austere ethnocentricity surrounding whiskey, and to understand it you must first respect it. Twenty years later, I still feel the sting of the tongue-lashing I took from that particular gin-blossomed Highlander for my wrongheadedness: “If ye ehver spek ta meh like that aggen en mi own place, laddie, I’ll toss ye owt on yer fookin’ arse.”

After my moment of whiskey clarity at Saucy Mary’s, I became, out of shame, a Scotch drinker. Johnnie Walker Black was my brand of choice, and by my late twenties I’d gotten where I believed I had no tolerance for inferior whiskeys. Analysis of the single malts’ subtleties bored me, and I found discussion of the flavor profiles of different varieties brutally tedious. Johnnie Walker fit as well as a trusted pair of boots, and like broken-in leather, it felt good and carried me where I needed to go. But more important, if I was civilized enough to appreciate the King’s Whisky, what else was there to discuss? It was just that simple.

Lessons being one thing, my epiphany came at a liquor store in Richmond, Virginia, several years later. On a January duck hunting trip, a good friend was espousing the nuances of different barrel-aging techniques of a particular Scotch when I began to feel the “Isle of Skye shame” again: Here we were celebrating the Scots’ triumphs at the still when for the last two hundred years our own countrymen had been laboring over a formidable American spirit of their own. The hollows of Appalachia are home to generations of bourbon, rye, and corn whiskey distillation, and I realized I’d never really stopped to give American whiskey due consideration. It was the beginning of a dangerous passion for me.

That passion has since grown into obsession. I have sipped and studied my way through every distillery I can find, both

licensed and illicit, and have even dabbled a little in production. But where the rubber meets the road is where simple enjoyment gives rise to a profound understanding of who our people are, where they have been, and what they have endured. In this sense, sipping a good glass of bourbon is a bit like tasting the history of the American South. Bourbon making, like other great traditions, has survived the Civil War, Prohibition, segregation, and civil rights, and quality has prospered as a result of the hardship. Today American distillers are making hooch that stands tall with that of their European counterparts.

I proudly drink American now, and I choose bourbon over anything else because I love its sweetness and the flavor of the grains. But I enjoy it because it speaks of the South and a respect for our traditions. And while I don’t necessarily wince when someone approaches my bar and orders an Irish whiskey, I certainly understand my Scottish barkeep’s indignation a hell of a lot better.

John T. Edge, writer and host of the television show TrueSouth, began contributing to Garden & Gun in its first year of publication. He is the author of The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South and House of Smoke.