I have a deeper relationship with my cast-iron pan than I do with some family members. Proud and protective, I brag that I can fry a perfect egg with barely a slick of butter, and guard against well-meaning guests who might plunge the pan into a sink of hot sudsy water. When food does cling, I ease it off with an amalgam of oil, salt, and love.

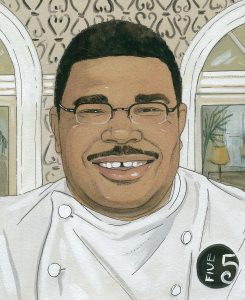

Banks White knows this kind of love, for from a great cast-iron pan springs a great hoecake—and he makes a great hoecake. On paper, White’s cooking experience belies his inner Texan. He’s a classically trained French chef who made his way from a small Texas town to the New England Culinary Institute to California’s Napa Valley. Now he’s executive chef at Five restaurant in the Hotel Shattuck Plaza in the heart of Berkeley, California.

White has discovered that a plate of well-prepared collard greens can make seasoned Northern California produce snobs swoon. “I had someone come up to me from Berkeley the other day who had never tasted collard greens or grits,” he says. “I had both on the menu.”

Like his grits and greens, White’s hoecakes trace back to his grandmother’s house in East Texas. Much like their Northern cousin the johnnycake, hoecakes are not much more than cornmeal, water, and usually some kind of leavening. Born of humble ingredients and field work, the name comes from the blade of a cotton hoe, which could easily be removed from its wooden handle and turned into a makeshift griddle. The cakes can be sweetened with sugar and take well to maple syrup. But White likes to fold in bacon and scallions to give them a savory character, and he lightens the texture with buttermilk and crème fraîche (sour cream works fine as a substitute).

White’s first law of hoecakes: Always use a cast-iron pan. His was passed down from his great-grandmother to his grandmother to his father and, finally, to him. “It looks just like a nonstick pan,” he says. “It’s beautifully slick.”