Don’t most Southerners have a quilt story? A sacred family heirloom tucked into a chest, or neatly folded on a bed, or maybe even a half-finished labor of love that’s currently draped across a sewing table? There’s something otherworldly about these striking fabric mosaics of Eight-Point Stars, overlapping Double Wedding Ring circles, or swirling flowers and birds in flight that have been touched by so many hands—the late Kentucky poet bell hooks admires the process just as much as the product in Appalachian Elegy: Poetry and Place: “sisters coming together / making peace / offering comfort / ways to warm / to open hearts.”

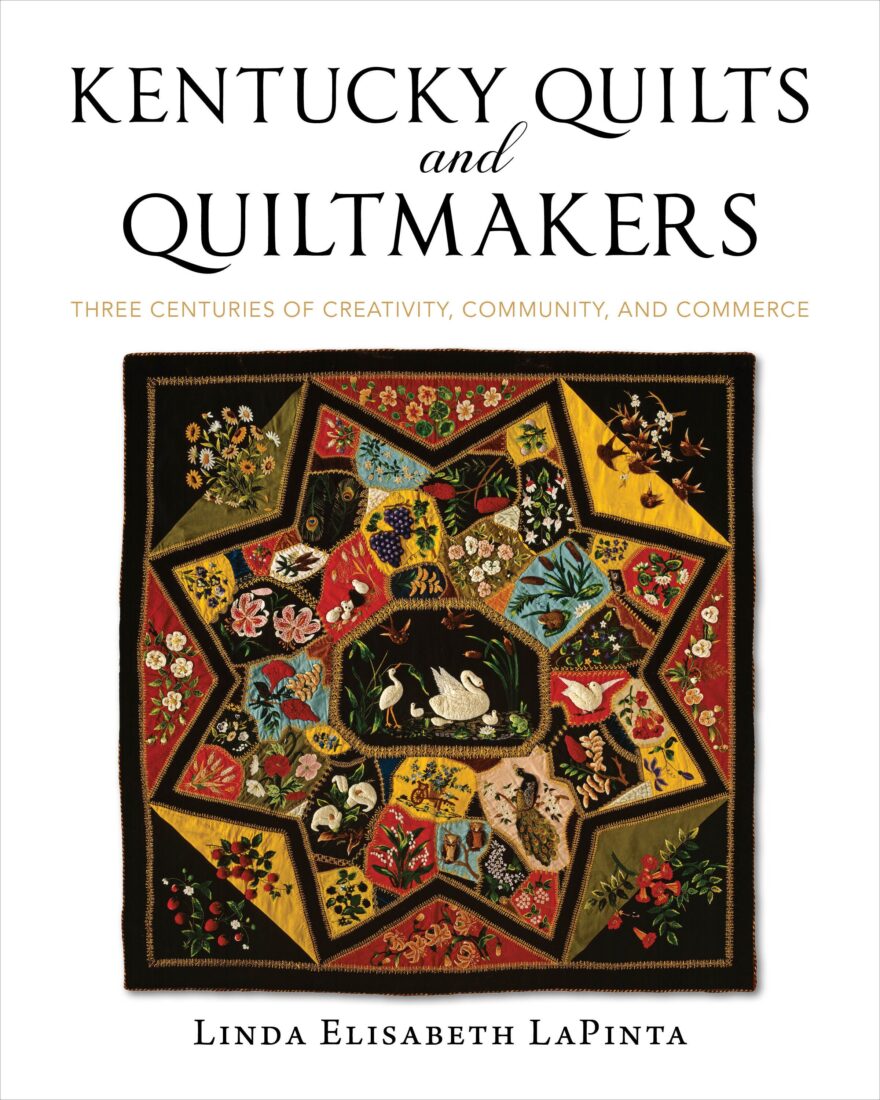

For Linda Elisabeth LaPinta, the author of the new book Kentucky Quilts and Quiltmakers: Three Centuries of Creativity, Community, and Commerce, hooks’s poem embraces an understanding of quiltmaking as a creative, community-oriented art form. For decades, many fiber artists—a majority of which are women—were excluded from the world of “fine art,” and their work was minimized as a domestic craft. Even Kentucky, a state teeming with a history of masterful textile artists such as Alma Lesch, lacked a formal appreciation for fiber arts. When the University Press of Kentucky asked LaPinta to write a book about Kentucky quilts, she was surprised that such a book had not already been published. “I realized that although two previously written books exist—one focuses on one area of the state while the other covers quilts and their makers from 1800 to 1900)—clearly, an update was in order.”

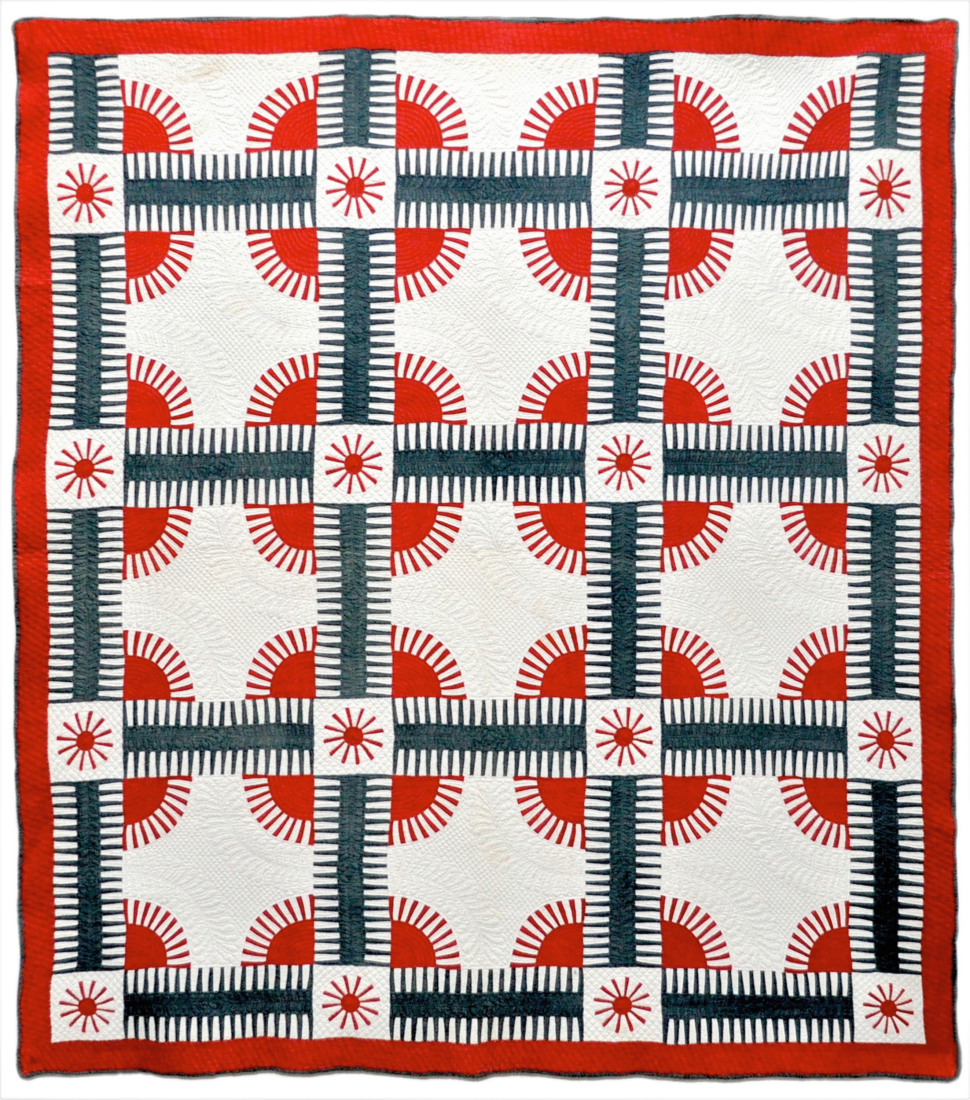

While quiltmaking isn’t unique to any specific place, Kentucky led the country in a series of “quilt firsts,” LaPinta says. The Bluegrass State introduced the first statewide quilt identification project, established in 1981, bringing in volunteers to study more than a thousand quilts and organize a survey exhibit; it also dreamed up and initiated Quilters’ Day Out (now known as National Quilting Day). “It was the first state to replicate the most significant quilt exhibition of the twentieth century, Abstract Design in American Quilts, an exhibit that had premiered in 1971 at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York,” LaPinta says. “It is truly remarkable to realize how pivotal the commonwealth is in terms of the role it has played in achieving quilt world firsts.”

The resulting book covers three centuries of Kentucky quilt and social history with dozens of interviews and photos of quilts from museums across the state. Beyond identifying aesthetic and stylistic changes in the art form since the late eighteenth century, Kentucky Quilts and Quiltmakers demonstrates the power of quilts to act as archival documents, a way to understand larger movements in Kentucky culture, politics, and industry—to admire a single quilt in LaPinta’s book is to admire a specific moment in history, captured by the imagination and hands of an individual artist or a collective.

The moody, jewel-colored crazy quilts of the nineteenth century mirrored an interest in Asian art and design after London’s 1862 International Exhibition, though many of the Kentucky quilts thread in specific Southern passions and stories as well. The elaborate patchwork of Annie Hines Miller’s Chester Dare Quilt, for instance, honors the oral history of the famous eponymous saddlebred in its ornate design. Within the asymmetrical patched square, a dark brown velvet appliqué of a horse stands against a dark teal background, surrounded by other animals and flowers—including an embroidered owl, cat, chicken, rabbit, daffodils, and daisies. But even as quilts reflect on well-known events and stories, they hold their own narratives, passed down through generations of family. “This quilt donor’s family legend has it that the maker of this quilt is said to have had hairs from the tail of Chester Dare taken to New Orleans to find a color of fabric that would closely match the color of Chester Dare,” Sandra Staebell, the Kentucky Museum registrar and collections curator, shares in the book.

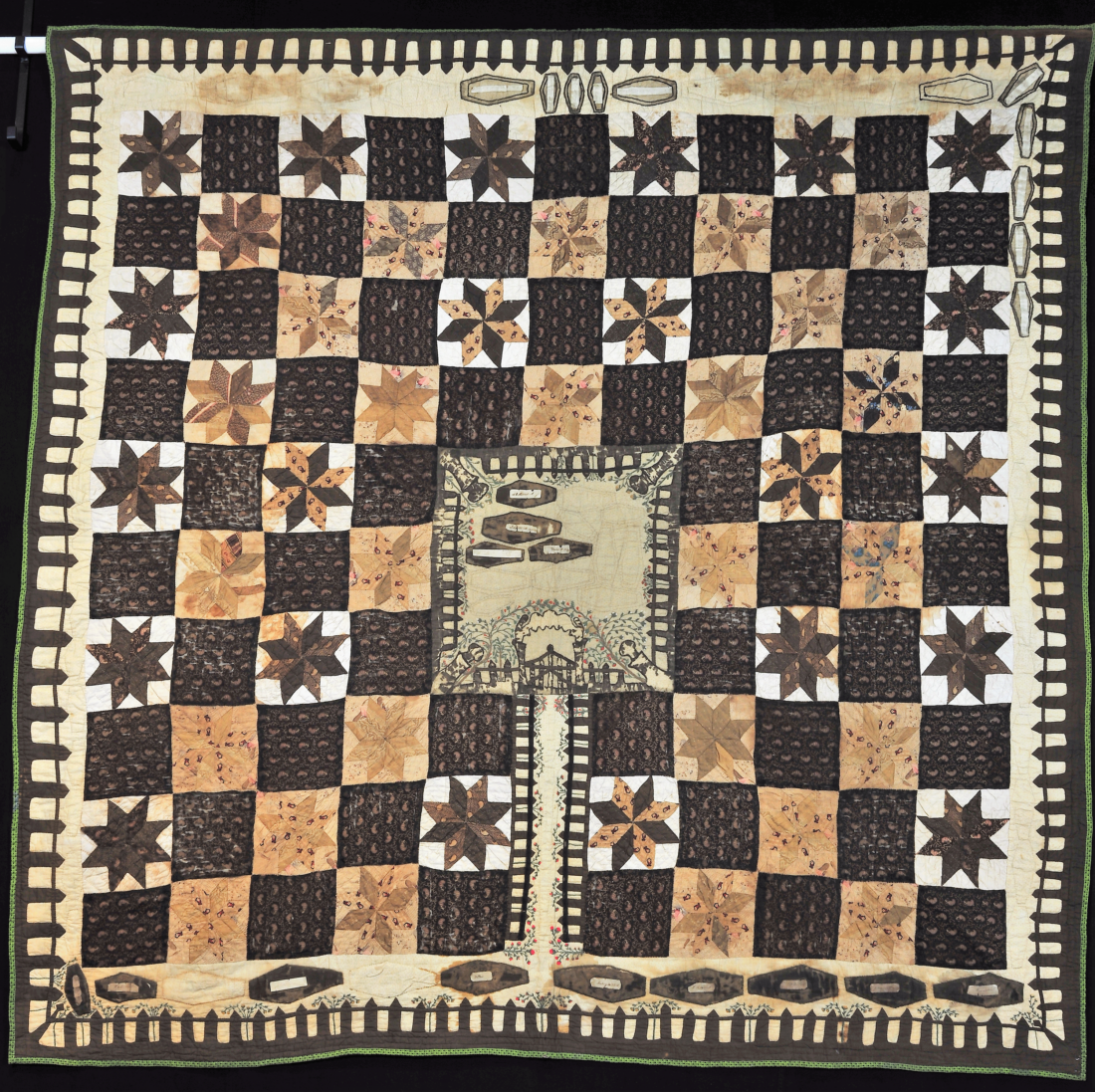

Some quilts, including the MacMillan Family Quilt, exemplify women’s involvement in the Civil War and efforts to offer comfort to their loved ones away fighting. Beyond providing warmth, heirloom quilts also acted as blankets for injured soldiers and identifying shrouds for the dead. Women came together to support soldiers, forming sewing circles and sending quilts to both Union and Confederate men. Others offer a visual narrative of family history and identity, telling personal stories of individual Kentuckians that remain untold in history books. Pieces like Elizabeth Roseberry Mitchell’s Kentucky Graveyard Quilt offer an intimate peek into the life of a Southern woman in the nineteenth century; completed by generations of Mitchell family women, the piece memorialized family deaths with coffin-shaped appliqués, which were moved from the outside frame into a graveyard with each passing.

Contemporary artists keep the rich tradition alive, reimagining what quiltmaking can be in the twenty-first century, whether as a teaching tool or community-building experience. “The most important aspect of quiltmaking to me has been employing quilts as a vehicle to communicate stories,” shared Nancy Dawson, a current Louisville quiltmaker, with LaPinta. Dawson explores Black history and social justice in her visual storytelling, such as in her piece Primary Sources, in which she includes excerpts of slave codes to highlight the difficult history of runaway slaves in Tennessee. “What’s more, these interviews underscore what seems obvious but has been too long ignored: The last sixty or so years of quilt history are history,” LaPinta says. “Too many quiltmakers interested in quilt history study only quilts and quiltmakers prior to 1960. I think that is because it’s human nature not to regard one’s own lifetime as being part of history when, of course, it is.”