Aaron Goldfarb met his first self-proclaimed “dusty hunter” in 2012. An author and journalist, Goldfarb had written extensively about craft beer, whiskey, and other spirits for a variety of publications, but back then, he wasn’t yet familiar with the term. “I asked, ‘What’s a dusty hunter?’” he recalls. “He said, ‘Well, I drive around Los Angeles, and I go into liquor stores, and I check to see if they have old bottles from the past, usually covered in dust.’ I said, ‘Why would you want to do that?’”

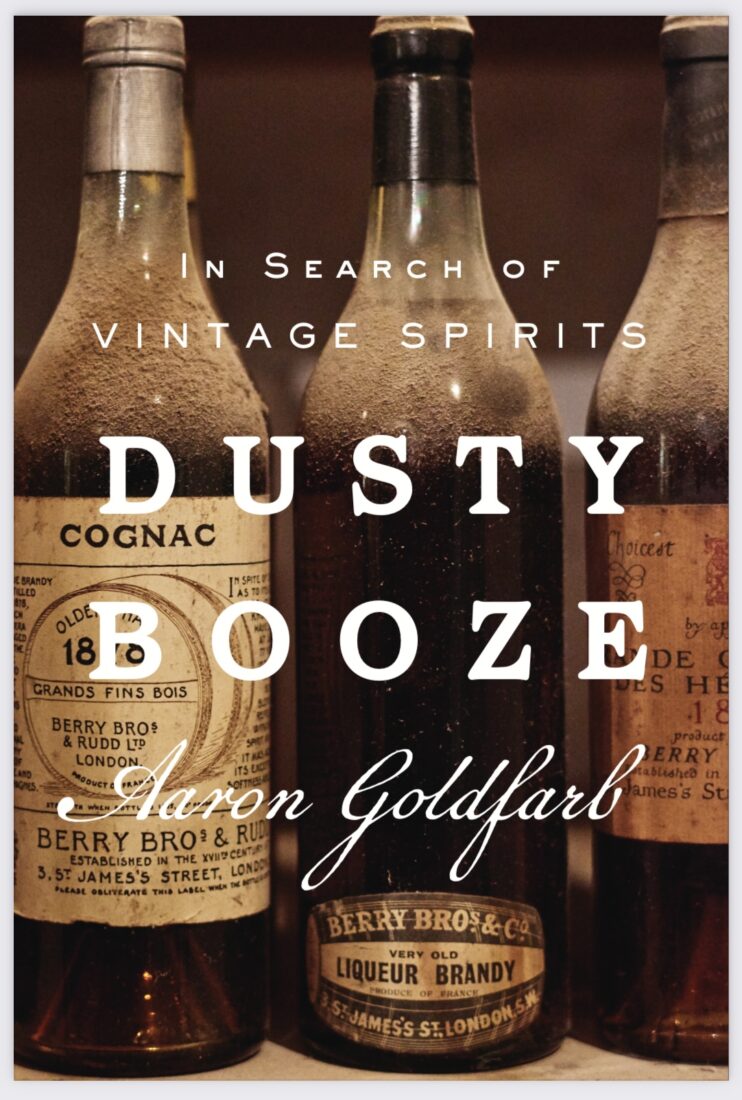

As Goldfarb would learn, vintage spirits aficionados are a special breed, and his new book, Dusty Booze: In Search of Vintage Spirits, explores the appeal of old bottles of bourbon, rum, tequila, and other spirits—and why collectors go to extreme lengths to track them down. He also explains—as his dusty-hunter friend did for him—how changing ingredients and production techniques have impacted spirits, and delves into the mystique of tasting what’s essentially a bottled time capsule. “He thought stuff from the past was better,” Goldfarb says. “And now that I’ve tasted a lot of it over the years, I, too, have come to believe a lot of it is better.” We spoke with Goldfarb about hunting dusties, prized bottles, and a rum no one will likely taste again.

How does vintage bourbon differ from modern bourbon?

Bourbon today is incredibly consistent. We have massive, computer-operated distilleries run by multinational conglomerates who want to ensure that high-quality product gets to every corner of the earth. If you go back to when fermentation happened in cypress tanks as opposed to stainless steel, it’s a less consistent process. There was likely more wild yeast in the air. The corn wasn’t as high yield. The oak trees used to make barrels were much older than today, and entry proofs were lower. I think all those things add up to eke out more flavor from spirits of the past.

Dusty hunters are a highly specialized and passionate subsection of spirit aficionados. What made you want to focus on the subject?

I love books that have nothing to do with alcohol but are about obsessives, like Susan Orleans’ The Orchid Thief. I mean, who’s interested in orchids? But it’s such a compelling tale. I wanted to write something equally compelling about this niche of esoteric obsessives. Rum obsessives are different from tequila obsessives, who are different from bourbon obsessives, but they all have a passion for finding the next unicorn and keeping their secrets close to their chest.

Kevin Langdon Ackerman is at the center of my book. He DM’d me on Instagram one day and said, “I think I have a story for you. I found the great Hollywood director Cecil B. DeMille’s booze stash in his house north of Los Angeles.” That story published in the New York Times in 2020. Then Kevin says, “If you think that’s a good story, I have an even bigger guy I’m pursuing.” Eventually, I pry it out of him that it’s Howard Hughes, which is the driving narrative of the book.

Do you have a sense of how much vintage booze is still unaccounted for?

When I first heard about dusty hunting, even then, people were telling me the game was over. You’re too late. Most stores are picked over by now, so you have to be a little clever. I tell a story late in the book about a guy who finds and buys at auction the entire contents of a liquor store in rural Illinois that had been sealed shut since 2006. Grimly, there are always people dying and we don’t know what was in their attics or basements. New bottles hit the fold every day.

As we entered the pandemic and maybe some people lost work or found that they had more alcohol than they’d ever need, a lot of these guys started thinning out their collections. You can still find just about anything on auction sites and sometimes even get a good deal because there’s so much hitting the market. But finding an incredible score at an estate sale or in grandma’s attic is still the crown jewel of vintage collecting, and much more satisfying than just hitting “high bid now” on an auction site.

Have recent laws allowing vintage liquor sales in Kentucky and Washington, D.C., helped bring dusty hunting out of the shadows?

Professionalization has certainly lessened the mystery of what’s out there. I talked to guys like Owen Powell at Neat in Louisville and Brad Bonds at Revival in Covington, [Kentucky]. They’ve built entire businesses and livelihoods around continuing to source bottles, and they seem to have no fear that they’ll ever need to find another job.

What are some of the holy grails of vintage liquor?

In bourbon, it’s still bottles from Stitzel-Weller that represent Pappy before there was a Pappy—those are typically seen in various releases of Old Fitzgerald or Weller throughout the years. Perhaps the unicorn of unicorns in American whiskey is Red Hook Rye, from here in Brooklyn. Initially, only several hundred bottles were produced, and I’ve personally drank four of them.

In rum, the big one is J. Wray & Nephew 17 [year old]. We’re pretty sure there are only two or three bottles left on planet Earth, and no one has the courage to open any of them. Then, in tequila, the big ones are the Robert Denton bottlings of El Tesoro and Chinaco from the early ‘80s to late ‘90s. That’s the first premium 100-percent agave tequila to make it to America.

Tequila is a fascinating subject to talk about vintage-wise. As of 2000, only two non-Mexican people or companies had any ownership or stake in tequila brands. So, within the past twenty years, tequila has gone from something people drank as a dare to something every multinational [spirits] conglomerate needs a few of in its portfolio.

Tom Wilmes is a journalist based in central Kentucky, specializing in bourbon and other spirits. A contributor for Garden & Gun, he has also written for Whisky Advocate, The Local Palate, Southbound, and various other publications. Follow @kentuckydrinks on Instagram.

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with Bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book. All books are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.