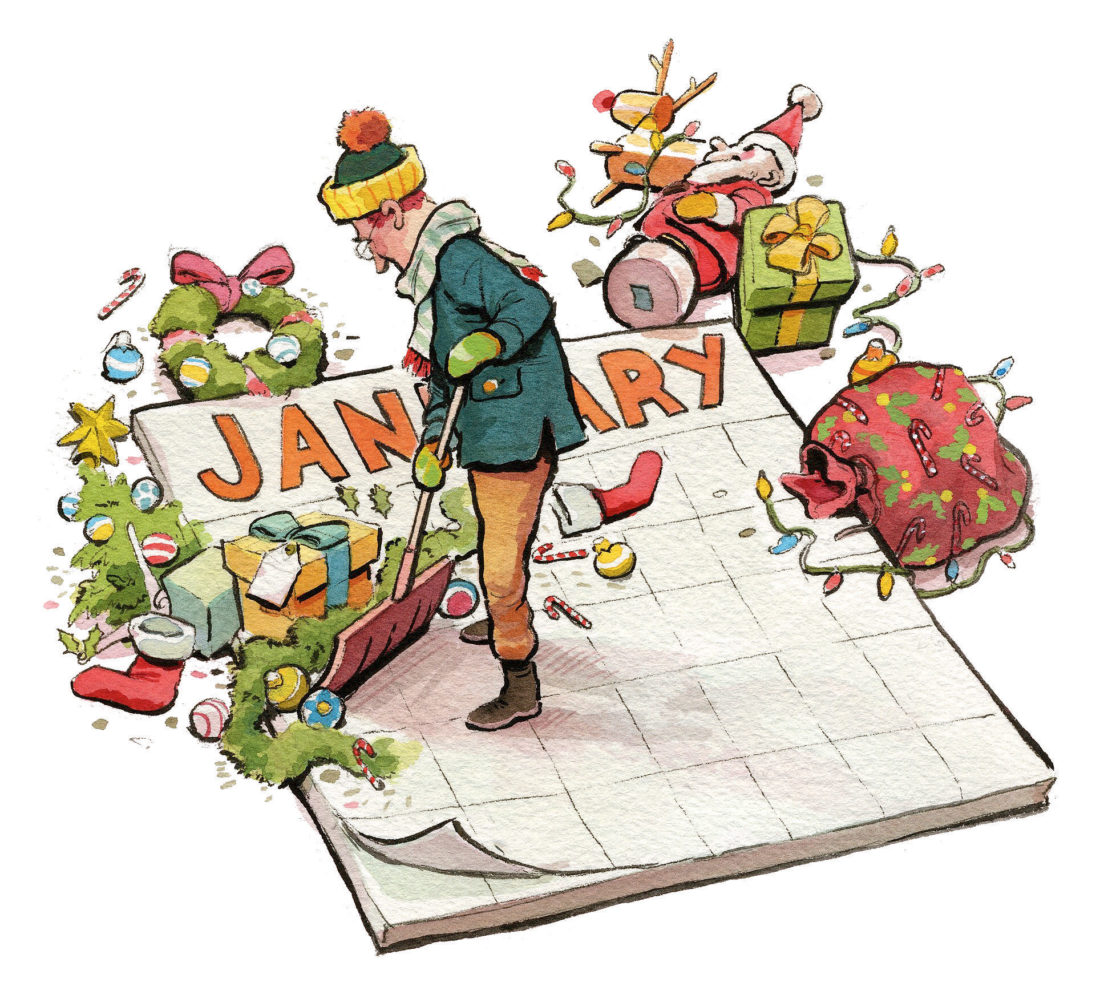

Q: My neighbor keeps his Christmas decorations up past New Year’s. Tacky, right?

A: Ain’t them neighbors a bitch. But, no matter how legitimate you may think your badge, your appointment as Xmas Decoration Cop is shaky. Offensive (to you) as the life-size illuminated Santa and reindeer are up on his roof, bathing your house in a heartwarming Walmart glow, do please dial back the policing. You must’ve not gotten the memo on the jolly, centuries-old holiday interplay of the Julian and Gregorian calendars. January 7 was Christmas for better than a millennium, until, in the 1580s, Pope Gregory XIII got fed up that Julius Caesar’s calendar, decreed before Christianity, scattered Easter across the church docket. Gregory wanted to fix the resurrection in one dependable spot, and in his doing so, Xmas got moved up by a couple of weeks. Epiphany, commemorating the coming of the Magi, remained on January 6. But, the English. They never listened to the popes. So, while the secular world goes (largely) for the Gregorian calendar, chunks of the liturgical world—the orthodox in Russia, the Levant, Egypt, and Greece—still celebrate Christmas in January. England, and its settlers here, didn’t get around to accepting the Gregorian calendar until the mid-eighteenth century. It’s perfectly acceptable to keep your decorations up through Epiphany. The queen, at Sandringham, keeps hers up till February. Why don’t you write in to Her Majesty’s Master of the Household about how tacky that is, and see where you get.

Q: What’s clabber, and why don’t we have it anymore?

A: The backbone of dairy farms prior to refrigeration, clabber is the South’s version of Scandinavia’s filmjölk or South Africa’s amasi. And we do have it, but mostly, only if you make it. Brought to the Appalachians by the doughty Scotch-Irish, bonnyclabber, as it is still called (from the Irish bainne, meaning milk, and clabair, the genitive of a word meaning sour thick milk), is raw milk that’s evolved into a specific, quite stable curdle. Clabber is a solid, like yogurt, but unlike yogurt requires no culture—the key to its robust tartness is that its native bacilli have been allowed to build their cities in the rich soup of milk proteins so that (and here’s where Mother Goose kicks in) the proteins bind into curds and the “water” in the milk becomes whey. Those bacteria have the power: Clabber will make bread rise, hence its inclusion in old baking receipts. Across the South, on every farm with a milk cow, the noun became a verb—“to clabber” meant to preserve milk in this way. My original clabber-girl grandmother Minnie was fed a bowl of it on her South Alabama farm every morning, spiced with cinnamon and molasses. We’re still debating whether the clabber or her hardy constitution was the key to her robust 104 years. Might want to set out a jar of raw milk in the cupboard and try some.

Q: Isn’t there some tie between moonshine and stock-car racing?

A: The bond is tight. Chary as I am to call upon the Scotch-Irish twice on a page, allow me to reassure you that it’s wholly logical for a group of settlers to be good farmers and to possess a talent for making fine firewater, an agricultural by-product. As the notion of the United States solidified into fact, part of the thinking was that a man’s home and livelihood were not entirely his. The South’s whiskey makers held the opposite opinion: Their corn belonged in the bottle, and the bottle was theirs. The insanity of Prohibition made a prized athletic ability out of these bootleggers’ driving skills in evading federal “revenuers.” From the popular dirt-track races the bootleggers staged on Sundays to keep sharp (after church, naturally), NASCAR was born. Almost all the early drivers—e.g., Lee Petty, Tim Flock, Charlie Mincey—had run shine. The Virginia-born Tom Wolfe’s brilliant 1965 Esquire profile of North Carolina stock-car legend Junior Johnson remains that history’s finest chronicle. Johnson kept his night job of running his daddy’s product. The revenuers couldn’t catch him on the road, so they staked out the family still and caught him firing it up. Johnson’s eleven months in prison made for barely a blip in his fifty-win career. Like all great bootleggers, he never looked back.