Feizal Valli pushes aside a thatch of plastic reeds and steps through a green curtain printed with ferns and banana plants. Black-and-gray hair cut in a modest pompadour, he wears black jeans and a black coat. From the Jungle Room at his new cocktail bar, set with backlit wildlife dioramas, he climbs wooden stairs bolted together like a high school shop class project.

“We’re going backstage,” Valli says as he ducks to enter a low-ceilinged three-table hideaway that overlooks the backside of his bar, the House of Found Objects, which opened last November in a downtown Birmingham storefront. “We like to blur the line between patrons and employees. Here, we’re all actors in the play.”

Below, clouds made of chicken wire and spray-foam insulation twirl on a ceiling mount above the main bar like a merry-go-round. Toy planes jut from those gray and white blobs, cartoon metaphors for the collision of soaring aspirations and everyday life. Thrift shop black-and-white televisions, tucked in knickknack shelves, broadcast aphorisms that inspire and confound, such as YOU ARE ONLY EVER AT WAR WITH YOURSELF.

Toward the rear, a rack of Elvis costumes stands opposite a selection of animal costumes, including a pink pig and an electric blue Cookie Monster. Beneath a second set of stairs that leads to a mezzanine, where couples play UNO and Cards Against Humanity, perches a Superman statuette printed with the slogan YOU ARE NOT REQUIRED TO BE INVINCIBLE.

Valli built this bar to stage a show that stars his regulars. It’s working. In early January, a woman put on that pig costume, took a seat in a nook beneath the cloud mobile, typed out a poem on a baby blue electric typewriter, and “mailed” it by dropping the index card in a black metal mailbox. (Valli collects the cards once a week and aims to publish a book of poems written by customers.) Two weeks later, a woman named Devin O’Neal ordered a drink called a Devin O’Neal, made in a coupe glass with pineapple rum and Earl Grey tea, and turned to see the black-and-white silent film she recorded in the video booth play across a giant screen mounted behind the bar.

In those moments, as regulars step into their roles, Valli sees his fever dream come true: “This is a play we cast nightly,” he says, handing over a boozy cocktail in an oversize rocks glass with an iceberg cube. “This is a large-scale art installation with a liquor license.”

Since moving from New Orleans in 2005, chased by Hurricane Katrina, Valli has built out three spots in Birmingham. First came the Collins Bar, which still operates a block away. There, he installed a wall chart of the periodic table that replaced abbreviations for chemical elements with abbreviations for Birmingham places and people. Next came the much-loved and now-closed Atomic Lounge, where he conceived an Alabama-centric mural done in the style of the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover. Under Valli’s spell, Atomic regulars transformed over the course of a night, propelled by stiff cocktails and a closet of thirty-plus costumes, free for the wearing. While costumes are still a part of Valli’s formula, his efforts now add up to something more. At the House of Found Objects, his nightly productions say to regulars, You are weird, you are seen, and we are in this together.

To pay tribute to patrons like O’Neal, Valli names his drinks after them. A Jack Crumpton, made with bourbon, Averna, and Campari, gets a sawtooth-cut lemon garnish secured with a miniature clothespin and a descriptor of “aggressive, stoic, dry” that applies to the drink and its namesake. Order a Cameron Champion (“sparkly, smooth, enticing”) and you get a bottled cocktail made with tequila, pomegranate liqueur, and grapefruit soda. The Legendary Sex Panther, the only Valli drink that isn’t named for a customer, is a riff on an old-fashioned, made with bourbon and chicory liqueur, served with a temporary panther tattoo and a moistened towelette. “The application is key,” he says. “That requires a kind of intimacy that bonds people.”

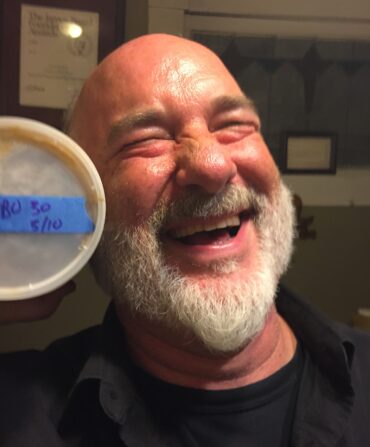

While many bars revolve around televisions, turned to sports or news, Valli’s big screen serves a different purpose. By late January, two months into the life of his new bar, patrons had recorded more than six hundred short and soundless black-and-white videos like the one O’Neal made. Flashing by in rapid succession, they play like a community portrait. A bald man gives himself what appears to be a pep talk while pointing at the camera. A woman with a pierced right nostril pulls off her false eyelashes. A boy of twelve, the son of a bartender at a nearby bar, grins and gesticulates, showing such aplomb and urgency that the crowd goes quiet to watch.

YOU ARE FIGHTING SOMEONE ELSE’S WAR, reads the legend printed on the check-pad cover for O’Neal’s bill. YOUR DAYS ARE NUMBERED! says the slogan printed on her receipt. Every prop Valli designed and built for this bar serves as a prompt to consider. As patrons watch videos of regulars, drinking cocktails named for regulars, he suggests roles to play as we move through his bar and our world, crossing over from lost to found.