Perhaps you will be shocked to learn that New Orleans takes Thanksgiving as an opportunity for more than just eating with family and falling asleep on the couch. For instance, the day has typically marked the opening of the season at the Fair Grounds Race Course. Ostensibly, the main event at the horse track is the Thanksgiving Classic, which has been run since 1924, seventeen years before Thanksgiving was even declared an official federal holiday. In reality, it’s an excuse for New Orleanians—who at that point have suffered something like three whole weeks since Halloween without an occasion to put on a costume—to don suits and fantastical headwear of all varieties.

Not far away, you’ll find counterprogramming in the form of the annual Human Horse Races, in which contestants ride on each other’s backs toward the finish line. Citizens of a healthier persuasion may wake early for the New Orleans Athletic Club’s Turkey Day Race, which turns 118 years old this November, while thousands line up the following night for the Bayou Classic Battle of the Bands, the epic duel of marching bands that, in most years, is a more exciting draw than the actual football game between Grambling State and Southern Universities. There aren’t many American ills that one can come to New Orleans to escape, but the plague of adult loneliness is one of them.

Bear in mind, the weather in late November is most often outright glorious—a second spring that fairly demands you get out into the sunshine.

All of this is to say that there are multiple reasons one would not want to spend a New Orleans Thanksgiving trapped in front of a stove. One solution is the tradition of deep-frying turkeys, which offers the dual benefits of being done outside (seriously, don’t do it indoors) and cooking the bird in an hour or less. The best plan, though, may be to get your seasonal cravings out of the way ahead of time, by eating one or more Thanksgiving po’boys.

New Orleans hardly has a monopoly on Thanksgiving sandwiches. It is a ritual in all fifty states to follow up the traditional feast with a mini one, composed of leftovers stuffed between two pieces of bread. At some point, the sandwich began coming before the meal itself—especially in New England, where such versions as the Gobbler, the Pilgrim, and the Puritan have long been cult items. (What’s more appetizing than a Puritan?) But here, where the tradition runs headlong into New Orleans’ sandwich culture, Thanksgiving po’boys have recently become a citywide phenomenon.

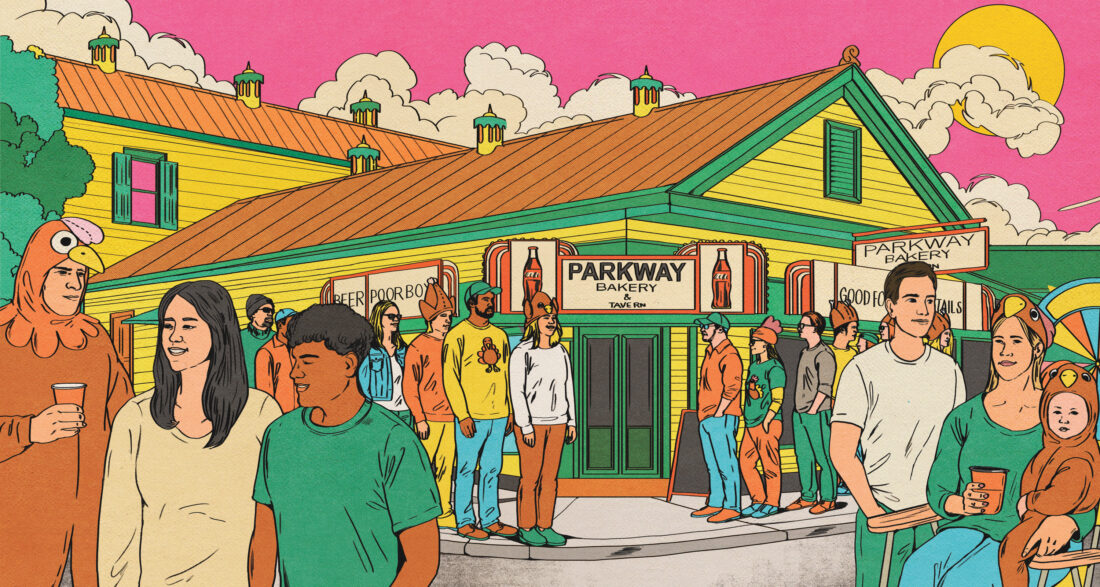

The mania dates to 2007, when Justin Kennedy started serving his Thanksgiving po’boy at Parkway Bakery & Tavern. That was only two years after Hurricane Katrina, and Kennedy, who’s now forty, had dropped out of college to help his uncle reopen the venerable sandwich shop. One day, one of their line cooks mused, “If you did a Thanksgiving po’boy, they’d be lined up down the block.” This was prophetic: Kennedy gave it a try, and within a few years the sandwich, now available only on Wednesdays in November, had become a sensation. In recent years, Parkway has sold as many as a thousand Thanksgiving po’boys per day.

“I’m talking about people waiting outside the restaurant in lawn chairs, dressed up in turkey outfits,” Kennedy says. “It just turned into something insane.”

Such is the po’boy hysteria that for many years I avoided even trying to score a sandwich. Last fall, I finally headed over, nearly panicking when I couldn’t find a parking spot. I speed walked up Hagan Avenue, past giant inflatable containers of Crystal hot sauce and Blue Plate mayonnaise, and up to Parkway’s front door. In prime New Orleans fashion, it felt like a fest. There was music playing and a wheel you could spin to win prizes. This isn’t so bad, I thought, looking around at the relatively modest crowd. Then I remembered it was 10:00 a.m.

Only a few years ago, the madness was enough to make Kennedy think of pulling the plug—exhausted by the toll one sandwich was taking on his staff and infrastructure. Then he had the idea of turning what had grown into a full-fledged event into a fundraiser for the Al Copeland Foundation, which supports cancer research in the name of the Louisiana restaurateur who founded Popeyes. Last November, Parkway’s Thanksgiving po’boys raised $50,000 for the foundation in four days.

Beloved as the Thanksgiving sandwich is, it offers certain obstacles from the standpoint of Sandwich Theory. Unlike most of the world’s great sandwiches, it does not have a built-in source of acid—the sharp pop that sauerkraut lends the Reuben, say, or pickled carrots give the banh mi. But the biggest challenge is softness—that is, how to keep your sandwich from turning into a pile of mush.

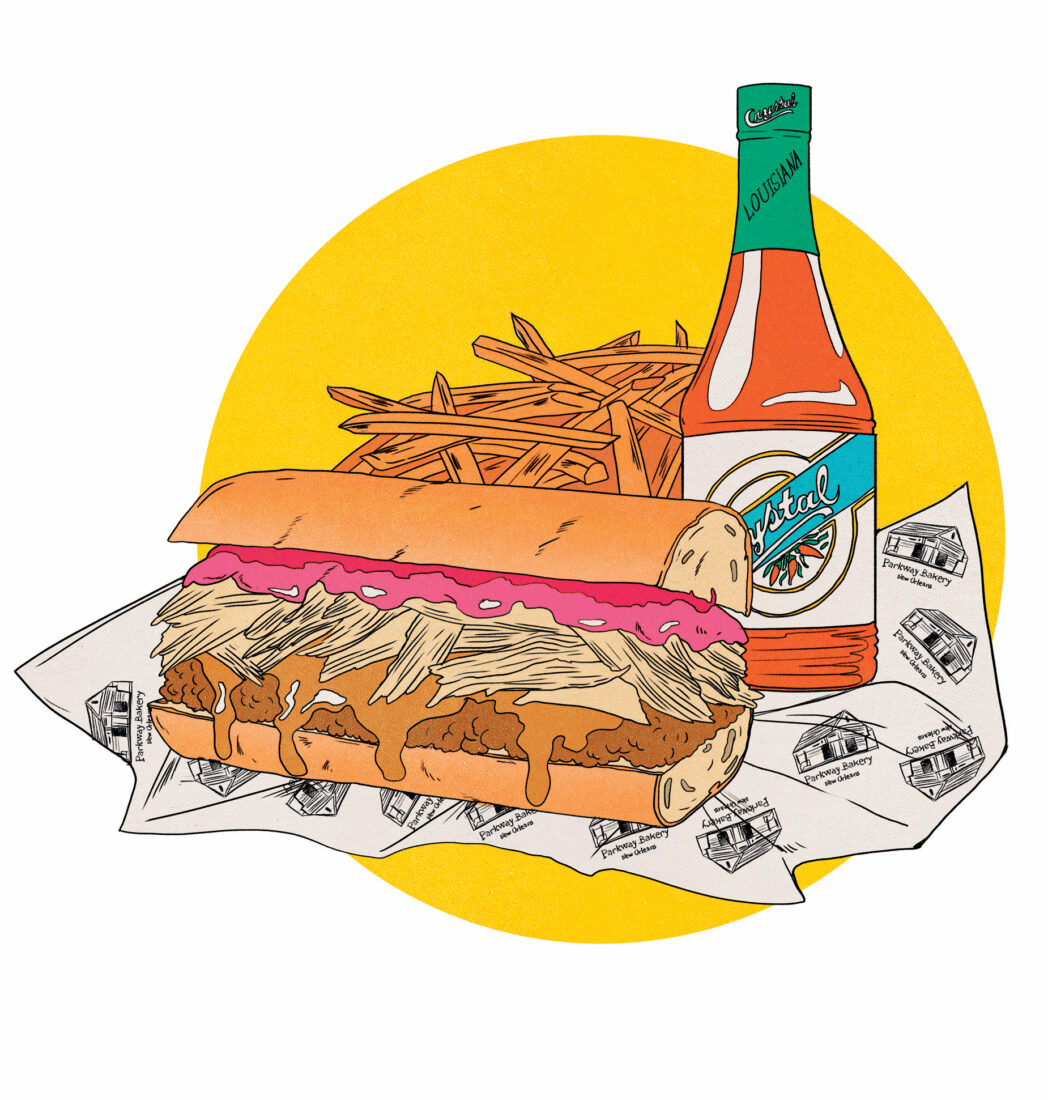

Parkway combats that issue by using lightly toasted bread from Leidenheimer Baking Company, provider of one of the crispier and sturdier po’boy loaves in town. The base is a layer of dressing made with dark meat, turkey stock, cornbread, and French bread, which is crisped in the oven before service. Next come slices of white meat, then a slathering of cranberry sauce and a few ounces of rich turkey gravy. The sandwich mostly holds together, though I wouldn’t go so far as to recommend eating it while wearing anything irreplaceable.

Other New Orleans sandwich shops have rolled out their own wrinkles on the formula. Sammy’s Food Service, on Elysian Fields Avenue, offers something closest to what you might make at midnight before Black Friday: soft and satisfying. Bywater Bakery layers its turkey, dressing, gravy, cranberry sauce, and mayo on nicely salty loaves of focaccia. In the French Quarter, Killer Poboys, a pioneer of neo-po’boys, serves what it calls the Gobbler, which comes stuffed with turkey, ham, sweet potato mash, and green bean and mushroom casserole, and topped with crispy fried onions and cranberry satsuma mayo. This reads like a monstrosity but is remarkably sound, with the ham providing salty ballast and the onions a welcome crunch.

Thanksgiving being as personal as it is, your response to any of these sandwiches may depend on any number of deep-seated associations: where you grew up, who cooked the holiday meal, your relationship with your mother, and so on. My partner instructs me to mention that none of the sandwiches contain enough cranberry sauce. I did not even give her a taste of the version at Francolini’s, which contains none at all. Tara Francolini, who has become the city’s foremost sandwich contrarian, hates the stuff and substitutes cranberry mustard instead. Her sandwich, named the Chandler, after a Friends Thanksgiving episode, comprises house-roasted turkey slices dunked in garlic butter just before serving, dressing, and a top layer of crushed salt-and-pepper potato chips.

With such bounty, no New Orleanian should ever want for Thanksgiving flavors. Kennedy reports that some customers line up the Wednesday before the holiday and order multiple po’boys without bread—the better to save for the next day so they can get their fix and be off to the races.